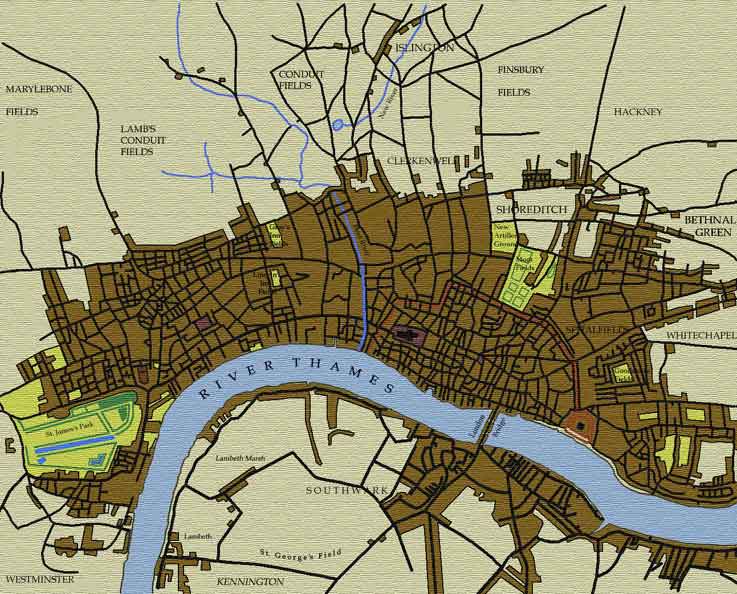

London ca. 1676

The Royal Exchange and the New Exchange

|

London in the Restoration and eighteenth-century

was a boom town, and, for those seeking luxury items, featured a number

of attractive and fashionable venues for shopping. The most important

of these were the two Exchanges, which functioned rather like 19th-century

shopping arcades, or the modern high-end shopping mall. Another central

shopping centre was located at Westminster Hall, in close proximity to

the nation's principal law courts. |

|

The Royal Exchange The Royal Exchange had been built

in 1567 by Thomas Gresham, who was impressed by the prosperous bourse

at Antwerp, and wished to provide for London a business centre that would

rival that of the Dutch. Gresham proposed building it at his own expense,

and the City corporation donated the land, demolishing eighty houses on

the site to clear sufficient space. The first Exchange was colonnaded,

with shops on the first floor, surrounding an open courtyard; it became

known as the Royal Exchange when it was officially opened for business

by Queen Elizabeth. Gresham's ambitions for the building were finally

realized in the seventeenth-century, for the Royal Exchange was to become

an immensely important centre for business and retail, and helped fuel

London's rise as a commercial centre. Gresham's Royal Exchange was destroyed in the Great Fire, and rebuilt according to a design, owing much to the original layout, by Edward Jerman in the mid-1670s. It remained a highly fashionable retail and social venue for the duration of the eighteenth-century, and was burned down in 1838.

The New Exchange was not at first terribly successful, and, in an effort to recoup expenses, its bottom floors were rented out as residences. However, with the development of Covent Garden and Lincoln's Inn Fields, and with the loss of shops and the Royal Exchange in the Great Fire, it became a very fashionable place to shop, and to socialize: references to it in Restoration comedy are almost obligatory. It included some excellent book shops. Its appearance during the Restoration was described by the visiting Grand Duke Cosmo of Tuscany:

The New Exchange was divided into four sections, with an "Outer Walk" and "Inner Walk" on each of the two floors ("Above" or "Below Stairs"). The lower floor had a reputation as a place for romantic assignations. The vogue for shopping in the New Exchange was, however, relatively short-lived, and the place lost much of its lustre in the reign of Queen Anne; it was taken down in 1737.

|

|

Website maintained by: Mark

McDayter

Website administrator: Mark McDayter

Last updated: April 25, 2002