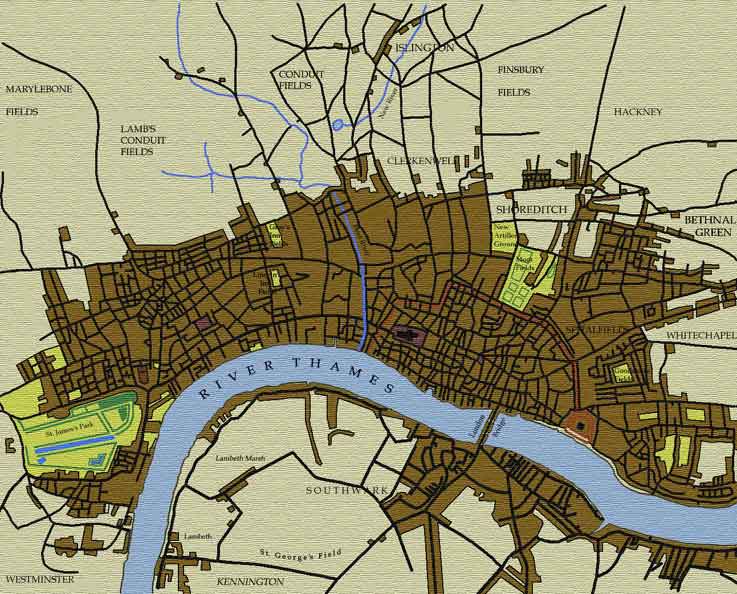

London ca. 1676

The Great Fire of 1666

|

The Great Fire of London began early on the morning of 2 September, 1666, in Thomas Fariner's bakery on Pudding Lane. Fanned by a strong east wind, it was soon spreading to neighbouring shops and houses, but failed to excite much alarm at first – the initial response of Thomas Bludworth, Lord Mayor of London was reputedly that "A woman might piss it out." Pepys too was unimpressed by what he saw early that Sunday. Yet, by the end of that first day, the fire had swept through the tightly-packed wooden structure of that quarter of the City, destroying, in the process, some 300 houses. |

|

By the next morning, the flames had begun to set ablaze the warehouses along the river banks, many of them loaded with pitch, tallow, and other flammable substances: fed by these, the fire become unstoppable. Much of the southern end of the City was now aflame, and panic had begun to take hold; citizens crowded the narrow streets everywhere in the city, carrying whatever of their movables they could manage. As bad as the damage of the first two days of the fire had been, however, it was the progress of the conflagration on Tuesday, 4 September that was most impressive. As the flames raced through the City, the first coordinated attempts were made to stem the flow of the fire by creating firebreaks: to this end, sailors being now employed to blow up houses in the path of the fire. Even this, however, proved ineffective: soon the Guildhall (which functioned as the seat of municipal government) and St. Paul's Cathedral were burning. John Evelyn reported that the destruction of the latter brought "Lead mealting down the streetes in a streame, . . . the very pavements of them glowing with fiery rednesse, so as no horse, nor man, was able to tread on them." When the roof of the old cathedral finally fell, it collapsed into the crypts below the church, which had become a makeshift refuge for hundreds of books from the booksellers whose shops lined St. Paul's Churchyard: all were immolated. By the end of Tuesday, the third day of the fire, the flames had leapt over the City walls to the west, and had even passed over the Fleet Ditch: the fire was now moving into the Town, and potentially threatening even Westminster. By Wednesday, however, the wind dropped, and efforts to create firebreaks – now directed personally by the King and his brother, the Duke of York – finally proved effective. The Temple burned, but, by the end of the that day, the fourth of the fire, it was clear that the worst was over. Some 430 acres – about 80% of the City – lay in ruins, and over 13,000 houses had been destroyed; John Evelyn estimated that there were some 200,000 refugees (almost certainly an overestimation) living in makeshift tents to the north of what was left of London. It was reported that only eight lives had been lost; what is more, the fire extinguished the last lingering remnants of the Plague had been devastating London over the last year and a half. Still, it was a calamitous event, and Londoners were soon searching for scapegoats. Many blamed the fire upon the French or the Dutch, with whom England was then at war: this xenophobic reaction resulted in the deaths of several innocent foreigners in the City. The most popular explanation was, however, that the fire had been the work of the popish conspirators, and it was this theory that was enshrined upon the base of the Monument, designed by Robert Hooke, and erected 202 feet away from Fariner's bakery in 1677. The process of rebuilding the City began, of necessity, quickly. Several proposals, including one each from John Evelyn and Sir Christopher Wren, were delivered to the King for the construction of an entirely new City plan, laid out along neoclassical lines, with broad avenues, magnificent monuments, and spacious public squares. A shortage of funds, and the absolute necessity of making a quick start on the rebuilding made these plans impracticable. Instead, new regulations were quickly enacted stipulating the size and construction of the new City housing. The old medieval street plan of London was retained virtually unchanged, but real improvements to sanitation, overcrowding, and communication within the City were made. The process of rebuilding was, of course, an involved and somewhat lengthy one, but proceeded, nonetheless, at a surprisingly brisk pace: a year after the fire, less than 200 new houses had been built, but by the end of 1671, there were 7,000 new buildings in the City. At the same time, public facilities and infrastructure were also completed at an impressive pace. Sir Christopher Wren was given the task of redesigning many of the City's new churches, including St. Paul's. The Great Fire had an enormous impact upon London: the City that burned between September 2nd and 5th was, essentially, a medieval one; the London that emerged from its ruins was, in seventeenth-century terms, a modern one. Improved sanitation meant that there would be no future visitations of the plague; at the same time, the fire itself contributed to the gradual depopulation of the City, and the shifting of wealth and population to the Town and suburbs of London. The London constructed in the aftermath of the Great Fire was, in essence, the London of eighteenth-century literature.

|

|

Website maintained by: Mark

McDayter

Website administrator: Mark McDayter

Last updated: April 25, 2002