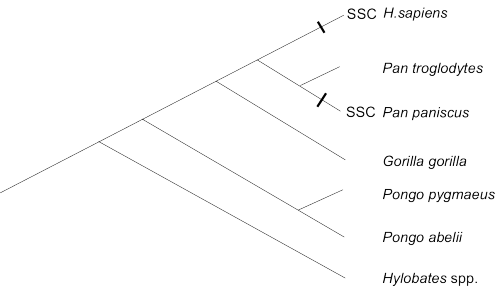

Taxon structure

What

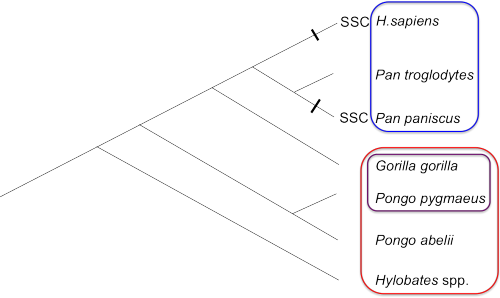

kind of taxon (mono-, para-, or polyphyletic) would be created by joining the two species that share the trait

"SSC" in the tree above? Before we consider this question, let us examine various ways of dealing with the problem.

The most widespread view,

almost always given in textbooks and strongly advocated by Wiley and

others disciples of Hennig, is whether or not a taxon contains (1) the

most recent common ancestor

itself and (2) all its descendents.

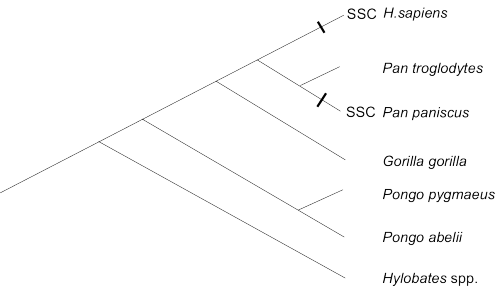

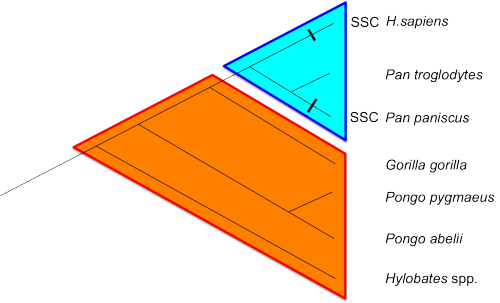

In the example above, a taxon that includes humans, chimps, and bonobos

is monophyletic because it meets both criteria. On the other

hand, a taxon that would include gorillas, orangutans, and gibbons

would only fulfill the first criterion, inclusion of the common

ancestor, but not the second, as some descendents (Homo and Pan) are excluded, and thus would be regarded as paraphyletic.

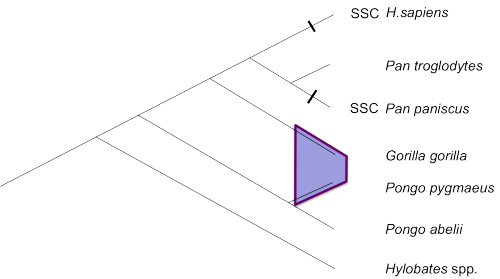

Last, a taxon that includes only gorillas and the Bornean orangutan

fulfills neither criterion as it does not include the common ancestor to

the two species and is therefore considered polyphyletic.

Easy enough, and in a conceptual context, these definitions of mono-,

para-, and polyphyly are clear and straightforward. The problem

arises when one leaves the Platonic world of concepts and instead

attempts to deal with the practical

reality of systematics. The many advocates of the ancestor

membership criterion nearly always fail to mention the small but

non-trivial detail that common ancestors are in practice never

available. Even the most recent common ancestors in our ape tree,

those of the two Pan species or those of the two Pongo

species, are extinct and may not have left any fossils; even if

fossils do exist, there is no way to demonstrate that a given fossil

truly represents the ancestor of a particular extant species. Lenski's frozen bacteria or Hillis's frozen bacteriophage

are rare exceptions where the common ancestor of a population (not a

collection of species) is known and available; but such situations are

not expected to occur in the natural world.

In other words, a

definition of taxon structure that involves membership of ancestor

species is completely unworkable in real biology. Practising systematists must use a different approach based on set structure.

Inferred phylogenies impose

onto taxa a nested set structure, based on presumed ancestry.

Members of nested sets constitute a clade. Taxa that belong to an incomplete nested set form a grade.

This ontology is entirely consistent with that proposed by

Hennig. For some unknown reason, he added the stipulation that

taxa must include the common ancestor. It is possible that Hennig's thought was distorted by translation and that he meant something else (share a common ancestor?). This said, E.O. Wiley and many other theorists continue explicitly and emphatically to

perpetuate this idea, which, if adhered to, would effectively seem to

preclude the description of most taxa above the species level.

Summing up:

- A taxon that includes all members of a nested set (clade) is monophyletic.

- A grade, or taxon whose members are nearest neighbours but from which a nested set is missing, is a

paraphyletic taxon.

- A taxon that consists of members of two or more incomplete sets is polyphyletic.

Hennig also used character mapping as a means of defining taxa in terms of phylogenetic structure.

A taxon that is defined by a ___

___ synapomorphy is monophyletic;

___ sympleisomorphy is paraphyletic;

___ homoplasy is polyphyletic.

But things are never simple. In our ape example, one might argue

that SSC-positive species acquired

this trait independently, in which case a taxon defined on the basis of

SSC would be polyphyletic. However, topologically, the two

SSC-positive species form a paraphyletic taxon because they share a

recent common ancestor but exclude one of its descents. This

would receive further support if one had evidence that SSC was present

in the common ancestor but was subsequently lost in the lineage that

led to chimps. So, nothing is black-and-white... Likewise,

there is no reason why we should not include, in our polyphyletic taxon

that contains gorilla and Bornean orangutan, their common ancestor.

Note that the current taxonomy of taxon structure has

never been universally accepted and is still the object of some

contention. Some authors have argued that paraphyletic taxa do

share a single evolutionary origin and so should be regarded as a kind

of monophyletic taxa. The term holophyletic would then

distinguish complete sets (clades) from incomplete sets (grades).

For further discussion of these matters, see Envall (2008).

Return to