Lecture 4

Economic Development Theories in Review

Harrod-Domar Model

This model,

developed independently by RF Harrod and ED Domar in the l930s, suggests savings provide the funds

which are borrowed for investment purposes.

The model suggests

that the economy's rate of growth depends on:

- the level of saving: measured by the Average

Propensity to Save = APS

-APC = savings/income

example: total income $1000, and savings $200. APS = 200/1000 = 0.2

- the inverse of the productivity of capital:

Measured by the Incremental Capital Output Ratio (ICOR)

-

ICOR = a required increase

in capital / income increase

For example, if $10 worth of capital equipment is needed to produce $1

more of output, the ICOR = 10/1 = 10.

The efficiency of the capital is the inverse of 10 = 1/10.

If $5 worth of capital equipment is required to produce one more dollar

worth of output, then the ICOR is 5/1=5.

The efficiency of capital is 1/5.

Compared to the previous example, now the capital is twice as efficient.

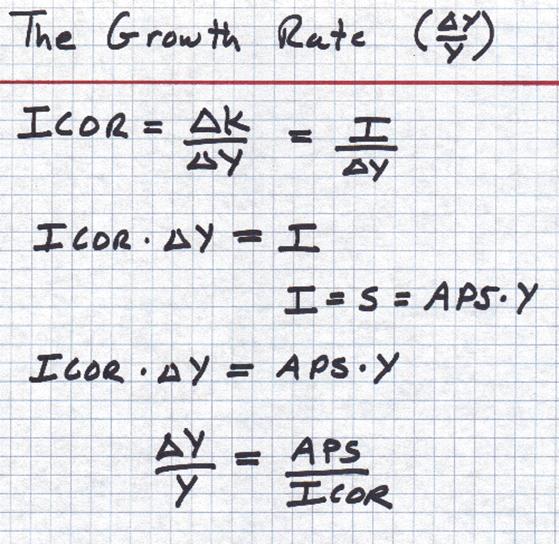

Mathematical-Formal Harrod-Domar Model: Calculating the Growth Rate of GDP

The growth rate of

GDP can be calculated very simply.

The ICOR is

defined as the growth in the capital stock divided by the growth in GDP. Since

Investment (I) is defined as the growth in the capital stock, the ICOR is equal

to Investment divided by the growth of GDP.

Investment will be

equal to savings and Savings is equal to the APS times GDP. If we divide both

sides by the ICOR and we divide both sides of the equation by GDP we have the

result that the growth rate of GDP will equal the Average Propensity to Save

(APS) by the Incremental Capital -Output Ratio (ICOR).

Thus if the APS is

12% and the ICOR is 3 the growth rate of GDP, G(Y), would be 4%.

|

|

|

|

Thus,

Growth Rate = Saving Rate x Efficiency of Capital

What

is taken for granted:

The Harrod-Domar model was developed to help analyse the business cycle. However, it was later adapted

to 'explain' economic growth. It concluded that:

- In general, economic growth depends on the growth

of labour L, capital K, and technology T.

Y

= f (K, L; T)

production function

dY =

f (dK, dL; dT)

However, the Harrod Domar model has only one

factor of production, that is, capital K. Why?

- As developing countries often have an abundant

supply of labour, it is a lack of physical

capital that holds back economic growth and development. In other words,

the bottleneck for the economic growth is dK or

an increase in capital.

- An increase in capital comes from investment.

- Investment = savings.

Implications

of the model

q

The key to economic growth is to

expand the level of investment: capital accumulation or í«Mobilization

of capitalí» is important.

q

Equally

important is the productivity of capital:

the lower the capital output ratio, the better.

In general, eventually, the more amount of capital,

the productivity of capital decreases:

The marginal product of capital decreases as the

amount of capital increases.

Recall: The S curve of the total output. In the latter part of the S curve, the

MP of capital is a decreasing function of capital –í░Decreasing Marginal Returnsí▒

or í░Law of Diminishing Marginal Returní▒

This happens as the size of capital grows in the

natural course of economic growth.

It is a formidable task to keep the marginal

product of capital constant or even increasing.

This can be achieved by generating technological

advances or technical innovations which enable firms to produce more output with less capital i.e. lower ICOR (incremental capital output ratio).

-

Some

countries have succeeded in mobilization of capital, but failed in the

efficient use of capital. Eg)

-

Kozo Yamamuraí»s

paper reports that during the take-off stage of economic growth of

q Policies are needed

to encourage savings; and/or to enhance efficiency of capital.

Problems of

the model

- Practically it is difficult to stimulate the

level of domestic savings particularly in the case of developing countries

where incomes are low.

- One way of supplementing the low domestic

savings would be foreign savings:

However,

borrowing from overseas to fill the gap caused causes debt repayment problems

later.

- The law of diminishing returns would suggest

that as investment increases the productivity of the capital will diminish

and the capital to output ratio rise. Fighting this natural law is a formidable

task.

In a word, the model does

not give any recipe for a success of economic development while it explains the

surface of the given economic growth.

Lewis's

Dual Sector Model of Development: The theory of í«trickle downí»

Lewis proposed his

dual sector development model in 1954. It was based on the assumption that many

LDCs had dual

economies with both a traditional agricultural sector and a modern

industrial sector.

The traditional agricultural sector was

assumed to be of a subsistence nature characterized by low productivity, low incomes, low savings and considerable

underemployment: the marginal

labor productivity is nearly zero.

The industrial

sector was assumed to be technologically advanced with high levels of

investment operating in an urban environment.

Lewis suggested

that the modern industrial sector would attract workers from the rural areas.

Industrial firms, whether private or publicly owned, could offer wages that would guarantee a higher quality of life than

remaining in the rural areas could provide. As the level of labour

productivity was so low in traditional agricultural areas people leaving the

rural areas would have virtually no impact on output. Indeed, the amount of

food available to the remaining villagers would increase as the same amount of

food could be shared amongst fewer people. This might generate a surplus which

could them be sold generating income.

Those people that

moved away from the villages to the towns would earn increased incomes and this

crucially according to Lewis generates more savings.

The lack of

development was due to a lack of savings and investment. The key to development

was to increase savings and investment.

Lewis saw the

existence of the modern industrial sector as essential if this was to happen.

Urban migration from the poor rural areas to the relatively richer industrial

urban areas gave workers the opportunities to earn higher incomes and crucially

save more providing funds for entrepreneurs to investment.

A growing

industrial sector requiring labour provided the

incomes that could be spent and saved. This would in itself generate demand and

also provide funds for investment. Income generated by the industrial sector

was trickling down throughout the economy.

Problems of

the Lewis Model

- Sustainable growth or steady job creation in

the urban sector is not automatic.

-The

assumption of a constant demand for labour from the

industrial sector is questionable.

-Increasing technology may

be labour saving, and reducing the need for labour.

-How much can the urban

sector absorb the migrants from the rural areas?

- Stability of economy might be adversely

affected by this kind of economic development. As the industry concerned

decline, the demand for labour will fall. The

industrial production may be more subject to business cycles while there

might be no business cycles in the subsistence economy.

- Will higher incomes earned in the industrial

sector be saved? If the entrepreneurs and labour

spend their newly found gains (Consumerism) rather than save it, funds for

investment and growth will not be made available.

- The rural urban migration has for many LDCs been far larger that the industrial sector can

provide jobs for. Urban poverty has replaced rural poverty.

Rostow's Model- the Stages of Economic

Development

In 1960, the

American Economic Historian, WW Rostow suggested that

countries passed through five stages of economic development.

Stage 1

Traditional Society

The economy is dominated by subsistence activity where output is consumed by

producers rather than traded. Any trade is carried out by barter where goods

are exchanged directly for other goods. Agriculture is the most important

industry and production is labour intensive using

only limited quantities of capital. Resource allocation is determined very much

by traditional methods of production.

Stage 2

Transitional Stage (the preconditions for takeoff)

Increased specialisation generates surpluses for

trading. There is an emergence of a transport infrastructure to support trade.

As incomes, savings and investment grow entrepreneurs emerge. External trade

also occurs concentrating on primary products.

Stage 3 Take

Off

Industrialisation increases, with workers switching

from the agricultural sector to the manufacturing sector. Growth is

concentrated in a few regions of the country and in one or two manufacturing

industries. The level of investment reaches over 10% of GNP.

The economic

transitions are accompanied by the evolution of new political and social

institutions that support the industrialisation. The

growth is self-sustaining as investment leads to increasing incomes in turn

generating more savings to finance further investment.

Stage 4

Drive to Maturity

The economy is diversifying into new areas. Technological innovation is

providing a diverse range of investment opportunities. The economy is producing

a wide range of goods and services and there is less reliance on imports.

Stage 5

High Mass Consumption

The economy is geared towards mass consumption. The consumer durable industries

flourish. The service sector becomes increasingly dominant.

According to Rostow development requires substantial investment in

capital. For the economies of LDCs to grow the right

conditions for such investment would have to be created. If aid is given or

foreign direct investment occurs at stage 3 the economy needs to have reached

stage 2. If the stage 2 has been reached then injections of investment may lead

to rapid growth.

Limitations

q

Many development economists argue

that Rostows's model was developed with Western

cultures in mind and not applicable to LDCs. It

addition its generalised nature makes it somewhat

limited.

q

It does not set down the detailed

nature of the pre-conditions for growth: what brings about the take-off?. In reality policy makers are unable

to clearly identify stages as they merge together.

q

Rostow does predict that

every economy is going through the same stage. However, some economies are

stuck in the first stage forever while other economies í░take offí▒. The development pattern or growth path

is not deterministic at all. Rostow model does not

tell these differences.

q Thus as a predictive model it is not very helpful. Perhaps its main use

is to highlight the need for investment. Like many of the other models of

economic developments it is essentially a growth model and does not address the

issue of development in the wider context.

Neo-Classical

Theory of Growth

Neo classical

theory maintains that economic growth is caused by:

- increase in the labour

quantity (population growth)

- improvements in the quality of labour through training and education

- increase in capital (through higher savings

and investment)

- improvements in technology

You may recall the two building

blocks for this theory from macroeconomic theories:

(1)

In the long-run, the

equilibrium national income is determined by the long-run aggregate supply

curve.

(2)

Neo-classical Production

function or Long-run Aggregate Supply curve.

Y = f(K,

L : Technology) for LRAS

(3) As K, L or T rises, the

LRAS curve shifts to the right and the Yf , which shows the maximum potential level of income, moves

to the right.

Underdevelopment

is seen as the result of some bottlenecks

that hinders the full utilization or accumulation of production factors, such

as K, L, or technical innovations.

For instance, first and foremost, the state

intervention in markets through regulation of prices may hinder the full utilization of production

factors. It inhibits growth because it encourages

corruption, inefficiency and offers no profit motive for entrepreneurship.

The neo classical

economists argue that for economic

growth, the bottlenecks should be removed. For instance, government control should be

removed.

They argue

therefore, that very often, the root cause of underdevelopment lies with the governments of the LDCs themselves. Only when governments adopt polices that

aim to free up markets and improve the supply side, will the economy grow and development occur. This results in a shift of the long-run

aggregate supply as shown in the diagram. The potential level of output of the

economy is then higher.

Neo classical

economists advocate the following strategies should be encouraged:

- Competitive free markets

- Privatisation of state owned industries

- A move from closed (no trade) to open

(trading) economies

- Opening up the domestic economy through

encouraging free trade (i.e. abolish tariffs and quotas) and foreign

direct investment.

These policies

will stimulate investment, higher output and income and hence higher savings.

Problems of

the model

This model makes a number of unrealistic assumptions

and ignores a number of crucial issues

- The assumption is that the creation of a free

market and a private enterprise culture is possible and desirable.

- The existence of market failure such as

externalities associated with economic growth are ignored

- The problem of uneven distribution of income

is ignored.

Empirical

Extension of Neoclassical Model: í«Growth Accountingí»

This theory identifies the

attribution of each factors, K, L (=N at macro level), and T to economic

growth.

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

Implications

q The higher

the K/N, the higher per capita income or output Y/N, and thus the standard of

living.

q Is that

the higher K/N (without the backing of a higher rate of savings), the

better? Yes, as we have seen, for

one point of time. But, not for a sustainable period of time.

Example) foreign aids of capital goods(externally increased K/N); a one-time increase in

capital(exogenously increased K/N)

-Note that there is such a thing as í░Optimal

Level of Capital Per worker or per capita, here given as K*/(N):

recall the picture is for one person, and thus K* should be read in fact as

K*/N. if

actual K/N is above K*/N, there is an excessive amount of capital(too much of

investment), and if the actual K/N of the economy is below K*/N, there is insufficient

amount of capital.

-We note that this has some elements of convergence

theory: economic growth rates would be higher when K/N is low, and the rates

will fall as K/N rises.

q We can get a steady state per-capita income rising by having a permanent

and sustained shift up of í░savings curveí▒. The curve rises up as the

domestic savings ratio (S/Y) rises. Note that an increase in the total amount

of Savings is not sufficient, but the savings ratio itself should rise. In

other words, a larger share of income should be saved. How does it show on the graph?

q An easy way of increasing K/N is controlling the population through birth

control. How does it show on the graph?

q A once-and-for all increase in capital or scattered investment does not

lead to an increase in per-capita income at all. For instance, í░Great Leap

Movementí» would not help bring an increase in the national income forever. Why?

How does it show on the graph?

q You can add the foreign savings, through capital inflows or foreign

borrowings, to the curve. This will lead to a higher equilibrium for the steady

state national income per person. However, this injection of foreign investment

should be continuous, not just one shot, in order to raise the equilibrium

level of per-capita income. For instance, foreign aids do not help raise the

standard of living of a country permanently. Why?

q So far we have assumed that Technology is fixed. However, you can shift

up the equilibrium per-capita income by having Technical Innovations. How does

this show in the graph?