The Weekly Literary Term

English 1020E

Section 002

|

Monday, 4 March, 2013 Elegy — In origin, the term "elegy" signified a particular form of classical verse in Greek and Latin. "Elegiac couplets" were a formal feature of certain kinds of poetry, used for a variety of subject matter, including humour, love, and death. The initial adaption of the elegiac form in English, in the 16th century and earlier, reflected this broad understanding of the nature of the elegy. John Donne's "Elegies" were not merely love poems, but frequently deeply erotic in tone and subject. Increasingly through the 17th and 18th centuries, however, the elegy became associated with serious and melancholy reflections upon death and loss. This was particular true of the "pastoral elegy," a subgenre that employed a pastoral setting to explore themes of loss, mourning, and consolation. What makes the pastoral elegy distinctive (aside from its employment of pastoral settings, characters, and conventions) is the fact that it represents a kind of poetic process, a "working out" of grief by the poet. Most usually, the pastoral elegy begins from a position of intense mourning, and concludes, finally, with acceptance and consolation. Characteristically pastoral elegies include some or most of these elements:

Not all elegies, or even pastoral elegies, include all of these features, and many of the best play with or against many of these conventions.

Monday, 25 February, 2013 Repetition with Variation — The notion that a literary work produces meaning through a repetition of narrative event, language, or theme has long been associated in particular with drama criticism. The fundamental notion is that a narrative will feature a recurrence of an important event that may appear to be so different from the original that the fact that it is a repetition need not even be immediately apparent. Both the similarities and differences between the repetitions are the way by which the meaning is produced. The similarities highlight the importance of the events and the themes it introduces, while the differences suggest change, or some other agent for difference. The Modernist novelist E. M. Forster, in his study of fiction, Aspects of the Novel (1927), applied a similar idea to the novel form, arguing that novels are structured according to a characteristic rhythm that he calls "repetition plus variation." It can be argued, in fact, that repetition with variation is an absolutely central principle to all aspects of literature. For instance, the rhyme shared by two lines of poetry is really a repetition of the same same vowel and consonant sounds, but with a difference. Milton's Paradise Lost contains numerous thematically important instances of repetition with variation, when language or incidents within the narrative seem to "mirror" each other. Thus, Satan's "heroic" actions are repeated, in a more truly heroic way, by the Son, while Eve frequently "repeats" Satan's sinful mistakes in a way that both foreshadows her doom, and suggests a similarity in their respective natures. A linguistic repetition with variation in the same poem occurs when Satan's assertion that "The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven" is echoed, with a vital difference, by the Angel Michael, when he promise Adam that he and Eve "shalt possess / A Paradise within thee, happier far" than Eden.

Monday, 11 February, 2013

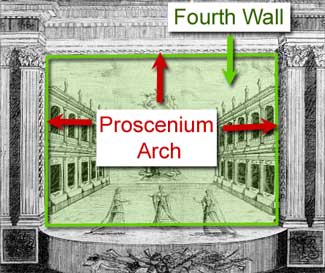

The idea of the "fourth wall" then is particularly applicable to "realistic" theatre, in which an extensive use of stage props and scenery produces the illusion of watching actual events unfolding behind the proscenium. In this context, the "fourth wall" functions as a transparent medium through which the audience is able to view the events played out on stage. When an actor employs an aside or direct address to the audience through this imaginary or transparent walls, it "breaks" the illusion and forcibly reminds us that we are, in fact, not voyeuristically watching "real" events and people, but actually witnessing a stage play. Many plays do this deliberately, in order to engage the audience more closely with the play, or to comment thematically upon the distinction between the "real" world of the audience, and the "art" world of the play.

Monday, 4 February, 2013 Heroic Couplet — Although it is most closely associated with the neoclassical literature of the late 17th and 18th centuries, the Heroic Couplet has been a popular verse form for many hundreds of years. Chaucer employed it in parts of his Canterbury Tales in the 14th century, and it is still occasionally used for modern verse as well. It is so called because it became particularly identified with "heroic" or epic verse and drama from the 17th century on. While it was considered sufficiently "elevated," expansive, and "lofty" for epic and quasi-epic forms, it was also versatile enough to be employed in a wide range of other genres as well. In form, the Heroic Couplet is generally two rhyming lines (AA, BB, CC, etc.) in iambic pentameter. A pentameter line is one that features 5 "feet" of two syllables each (for a total of 10 syllables in the line); in heroic couplets (as indeed in a great deal of English verse) the base meter of each of these feet is an "iamb," consisting of one unaccented syllable followed by an accented one: - / . As will be clear from the Heroic Couplet below, there is frequently some variation in the meter of individual feet, but the base unit from which each of these represents a variation is always an iamb. Each line of the couplet is often divided by a "caesura," or slight pause, generally at or near the middle of the line. In the example below, the caesura follows on the 5th syllable of each line, and is more pronounced (because of the comma) in the seond line than in the first.

Because of its two-line structure, the Heroic Couplet is an ideal form for the drawing of comparisons, since one line can be devoted to each of the two terms or ideas being compared. Additionally, the caesura within a line can also be used to invoke a comparison within one of the lines, as in the second life of the example above. Verse using the Heroic Couplet occasionally introduces variants, such as the Alexandrine (a single 12 syllable line), or "triplets," which are three rhyming lines (AAA). Alexander Pope is generally acknowledged to have been the greatest and most skilled practitioner of the Heroic Couplet, but it has been a common enough form in English verse that there are a great many poets who have demonstrated skill in its employment.

Monday, 28 January, 2013 Decorum — Classical writers and rhetoricians believed that verisimilitude (i.e., realism) was better achieved when the "style" of a work matched with its subject. In an age that was very strongly hierarchical in its beliefs and values, this meant, in practice, that an "elevated" style should be employed to describe a subject that was itself "high"; conversely, "low" subject matter required a less elevated style of language and form. For this reason, then, epic poems or romances, that were (by definition) about heroes, kings, and great deeds, should be written in a form of language recognized by readers and critics as elevated. Similarly, a comic subject matter, which generally focussed upon characters who were lower on the social scale, should use a lower form of language. As Horace expresses it in his Ars Poetica:

A variation on this idea, decorum personae, or "decorum of the person," dictated that characters should speak a language appropriate to their stature (usually defined primarily as their social rank). Violations of decorum were seen as producing a ridiculous and incongruous effect. Sometimes, however, a writer might wish to achieve this kind of incongruity and humour deliberately, as in travesties, burlesques, and mock heroics and epics; where this was the case, the writer might deliberately violate decorum.

Monday, 21 January, 2013 In medias res — The term "in medias res" means literally "in the middle of things," and refers to the literary and narrative technique of beginning a story, not at the beginning, but part way through. Early parts of the narrative are then revealed throughout the story by means of flashbacks and inset stories. The term is most often associated with epics, which most frequently begin this way, but can be employed in reference to other types of story as well. It is originally from the Roman poet Horace's Ars Poetica, a 1st Century BCE poem on the subject of literary criticism:

Beginning a poem, and most especially an epic, in this manner can have a number of functions. As Horace's remarks above suggest, one advantage of this approach is simply that it sweeps the reader up into the action right away, instead of forcing her or him to read a long and possibly tedious "set-up" for the main narrative. It also means that the poet can employ interesting and thematically useful devices for telling the "back story"; Paradise Lost, for instance, begins this way, with the rebel angels' awakening in Hell, following their defeat by God and the Son. Elements of the story of the Creation, and the battle in Heaven between the Son and Satan and his forces is given, initially, by Satan; this account is later usefully compared with what we learn from God and the Son, and from the angel Raphael's detailed account to Adam in Books V and VI.

Monday, 14 January, 2013 Epic Machinery — The term "epic machinery" first arises in the Neoclassical period (roughly the 17th and 18th centuries) as a way of describing the characteristic appearance of divine and semi-divine beings in epic poetry. The term itself derives from the stage machines (i.e., cranes) that, in ancient Greek tragedy, were used for the entrance of gods on to the stage; "machinery" thus refers by anology to the introduction of these beings into epic, rather than as a description of the gods and other immortal beings themselves. In ancient epics such as The Iliad, The Odyssey, and The Aeneid, the gods are very much active participants in the events of the epic, assisting (or hindering) the hero; sometimes the conflict that makes up the main narrative is mirrored, as in The Iliad, by divisions within the ranks of the gods on Olympus. Milton's Paradise Lost Christianzes the epic machinery, and in the place of the pagan deities substitutes the Father, the Son, the archangels, and (of course) Satan. The best known description of epic machinery occurs in Alexander Pope's prefatory remarks to the revised and expanded version of his mock epic poem, The Rape of the Lock (1714), which introduces a pantheon of "sylphs" borrowed from Rosicrucian mysticism as parodic representations of semi-divine beings:

Monday, 7 January, 2013 Accommodation — The theory of Accommodation is a Renaissance approach to understanding the language of the New and (especially) Old Testaments of the Bible. The theory was drawn most especially from an explanation in St. Augustine's De Civitate Dei (5th century CE) for the anthropomorphisms of the Bible, by which God is described in terms that sometimes seem crudely human, and that, if taken literally, might seem to undercut His Divine nature. Thus, for instance, if God is said to be "angry," it is not to be taken literally that He experiences the human emotion which goes by that name, but rather that some particular aspect of the Divine Nature (in this case, Divine judgment of wrong-doing and sin) beyond full human comprehension is signified this way by analogy. Milton applies the theory of Accommodation in a much broader way than was probably intended by the theologians who devised it and employed it in their explanations of Biblical passages. The part of Paradise Lost which seems to owe most to Accommodation is the lengthy account of the battle between Heaven and the rebel angels, which is described in very concrete terms that reflect the model of classical epic. Milton does not mean to suggest that combat was literally undertaken by angels in armour, equipped with shields and lances. Much of Paradise Lost, with its reimagined and speculative account of the Creation and all of the events leading up to the Fall, uses Accommodation in a similar way, but in an even larger sense, it is the means, through his use of a narrative poem, by which he explains the almost inexplicable -- the workings of Divine Providence -- to mere humans. As Milton notes:

Monday, 12 November, 2012 Carpe Diem — The phrase carpe diem is from the Latin, and is generally understood to mean "seize the day." The most important and influential use of the phrase is from Ode I.xi, by the Roman poet Horace: "carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero," which C. E. Bennett has translated as "Reap the harvest of to-day, putting as little trust as may be in the morrow!" The theme of "seizing the day" has been much explored in the literature of many Western languages, modern and ancient. In its most general sense, it simply suggests that one should live for today, because the future is so uncertain: in this context, the idea is associated with Epicurean philosophy, which proposed a materialist understanding of the universe, and argued that pleasure and contentment were not possible without first banishing the fear of the death. In the 16th and 17th centuries in particular, a number of English lyric poets adapted the phrase, but interpreted it somewhat more narrowly by applying it to the poetry of love and seduction: in this context, "seizing the day" means enjoying the fruits of love while one is still young and vigorous. Such love poetry (which is almost invariably and inevitably written by men) tends to dramatize an encounter with a desired woman, and employs the concept as part of an attempt to persuade her to abandon her virtue and chastity, and give in to the temptation to partake in sexual pleasure today. One notable expression of this idea appears in Robert Herrick's carpe diem poem "To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time" (1648):

Possibly the most famous carpe diem poem is Andrew Marvell's "To His Coy Mistress" (ca. 1650).

Monday, 5 November, 2012 Enjambement — Enjambement (which comes from the French enjamber, "to stride over" or "encroach") is the continuation of the semantic and grammatical from one line to the next. It is the opposite of an "end-stopped" line, where the end of a line of verse coincides with the conclusion of a sentence, or grammatically distinct part of a sentence, generally marked by punctuation of some sort (a period, a comma, colon or semi-colon). All of the lines from the opening of Alexander Pope's Rape of the Lock (1714) are, for instance, end-stopped: What dire offence from am'rous causes springs, The next couplet (two rhyming lines) in the poem, however, are enjambed, because the grammatical sense of the sentence is split between the two lines: Say what strange motive, Goddess! could compel Enjambement can have diverse effects, depending on how it is used. Generally, the emphasis in a line of verse falls most heavily on its beginning and end, but this pattern is disrupted in enjambed lines because the reader must "hurry" on to the beginning of the next line to make sense of the end of the previous one. One effect, then, can be to create a tension between the verse form and the grammatical sense of the words. Another can be to create a more "natural" or "conversational" effect in the verse.

Monday, 29 October, 2012 City Comedy — A City Comedy (or sometimes "Citizen Comedy") is a genre of play that particularly focusses on London, generally with satiric intent. "London," in this context, means in particular the middle and lower class citizenry associated with the economic, social, and cultural life of the old medieval City of London and its environs, as opposed to the more fashionable and aristocratic areas to the west of the walled city, in Westminster and the Court. In this sense, City Comedy is generally itself somewhat aristocratic in values and perspective, and targets the ignorance, pretensions, and supposed greed of London merchants, bankers, apprentices, and labourers, along with their wives and their general social and cultural milieu. Because of their social and cultural focus, City Comedies rarely feature "romantic" or "marvelous" elements, but instead purport to offer a "realistic" depiction of the mundane life of the citizens of London. They seek to reveal the avariciousness, hypocrisy, and misplaced social ambitions of the "lower orders" of society in a manner that caters in particular to a more socially elevated audience. City Comedies were popular between the late 1550s and the closing of the theatres in 1642, but particularly flourished in the reign of James I (1603-24). Playwrights associated with the genre include Thomas Middleton (1580–1627), John Marston (1576 – 1634), and (to a somewhat lesser degree) Ben Jonson (1572 – 1637). The form was to have some influence upon the Comedies of Manners that dominated the English stage following the Restoration in 1660.

Monday, 22 October, 2012 Romanticism — An artistic and cultural “movement” most usually associated with late 18th and 19th centuries, Romanticism found expression in nearly all facets of Western literature and art. The beginning of the Romantic movement is, in English literature, conventionally (if simplistically) dated from the publication by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge of The Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by these two writers, in 1798; an expanded edition of this appeared in 1800 with a new “Preface” by Wordsworth that articulated the central principles and “programme” of the new movement, at least as envisioned by Wordsworth. In practice, however, the Romanticism of the beginning of the 19th century was a natural outgrowth of tendencies in English literature that were already very apparent by the mid-18th century. The most important feature of Romanticism is probably the shift that it represents from a generally mimetic understanding of the function and nature of literature (literature is an “imitation of nature”) towards a more “expressive” view of it: literature was now increasingly seen as a expression of the poet's mind and emotional state. As Wordsworth put it in the “Preface” to the Lyrical Ballads , it was now “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” Other characteristic features of Romanticism include:

Although Romanticism never entirely displaced older, mimetic views of art, its rise to dominance is something of a watershed in the history of Western culture, representing a significant shift in cultural understanding and belief. It spawned its own opposing movements, mostly notably Modernism at the beginning of the 20th century.

Monday, 15 October, 2012 Romance — This is a term that has been employed in many different senses over the course of the last several hundred years. Medieval romances were tales of adventure involving knights, quests, damsels-in-distress, and themes of romantic love and faith. Renaissance Romances, especially those written in Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries, built upon the Medieval Romance by bringing to bear upon the genre more of the formal elements associated with classical epic; the best example in English is Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene (1590-1596). In the 17th century, the term came to be applied to lengthy works of prose fiction of the sort popularized by the French writer, Madeleine de Scudéry: these were, like the Renaissance romance, modeled loosely upon classical epic, and featured elevated heroes and heroines engaged in amorous adventures in foreign and exotic settings, in a classical or “oriental” past. By the end of the 17th century, William Congreve was distinguishing between the “fanciful” romance form, and what he called the “novel,” which was more firmly rooted in the day-to-day reality of the present. “Romance” continued to be used throughout the 18th century almost synonymously with the word “novel,” but there was at the same time an increasingly strong distinction between the older form, with its emphasis upon spectacle, exoticism, and elevated characters, and the newer genre, which relied greatly upon social realism for its effects.

Monday, 8 October, 2012 Mimesis — Often particularly associated with Aristotelian criticism, “mimesis” is the Greek word for “imitation.” It is most generally used in literary theory and criticism to refer to the ways in which a work of art “imitates” real life in its employment of characterization, setting, plot, and theme. Mimetic criticism, predicated on this notion that art is an imitation of the external world, dominated approaches to literature from classical times until well into the 18th century, when it was increasingly challenged by a growing admiration for “originality” and the development of expressive theories of literature. Mimesis in literary terms was never viewed as slavish; “nature” (in the broadest sense of that term) supplied the model, but it was the role of the writer to add “art” to his or her subject, and to, in Aristotelian terms, imagine a world that reflected our own, but that was “better” or “clearer” in some way. Because the subject of mimetic literature was Creation, which was the handiwork of God, Christian approaches to mimetic writing often likened the role of the artist to that of the Divine creator; the artist “imitated” God in her or his attempt to produce an image of a better world.

Monday, 1 October, 2012 Historicism — Broadly speaking, historicism is an approach to texts that attempts to understand them, from a variety of perspectives, in the context of the time in which they were created. The relationships between the work of literature and “its time” may include such things as the connections between the work and the political and historical events or personages particularly touched upon by it, the particular ideological, social, and aesthetic assumptions of the age in which it was produced, or the apparent polemical function or purpose of a work in relation to its “original” historical audience. Historicism does not deny that a work may continue to have meaning and value in new historical contexts, but it insists that a full understanding of a text can only be achieved through an exploration of its place within the original culture in which it was created. At its most primitive, there is a danger that historicism may sometimes reduce a work of literature to the status of historical “document,” a text that does little more than tell us about its historical origins. At its most sophisticated, however, histo, ricism provides invaluable insights into the relationships between writing and society, and in the capacity of art to both reflect and transcend its own historical moment.

Monday, 24 September, 2012 Subaltern — Although not specifically a "literary" term, the word "subaltern" is frequently used in literary and critical discourse associated with Postcolonial Theory and analysis. First employed in a Postcolonial context by Indian theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, the term is used to designate those peoples and cultures who have been subordinated and oppressed by Imperialism, and by the writings that uphold colonialism and racism. Although sometimes used loosely as a synonym for "oppressed minority," Spivak and others have insisted that the word should be applied correctly only to those who have been subordinated by the specific power structures (including writing) of Imperialism; those who are oppressed, but still functioning within an imperialist culture (as for instance the white working class in Western nations), may be oppressed, but are not truly "subaltern" in this sense. An important point about the subaltern is that, while it has been excluded from the structures of conventional power and denied the right to define itself, it is not without all power. Imperialist culture has used the exclusion of colonized peoples as a means of defining itself: one is defined as belonging to the privileged culture by virtue of the fact that one is not "subaltern." What this means is that, in terms of language, subaltern cultures can subvert Imperialism, colonialism, and racism by insisting upon self-definition. Change the meaning and substance of what it means to be "subaltern," and one necessarily changes, and subverts, the meaning of Imperialism, which defines itself in contradistinction. This is one of the endeavours of much "subaltern" writing: it employs language in this way to undermine the cultural assumptions that are the foundation of Imperialism.

Monday, 17 September, 2012 Persona — "Persona" is the term generally applied to a fictional "voice" or "mask" that is often adopted by an author in a poem or prose work. The term has literary antecedents that stretch back into classical dramatic theory (the word comes from the Latin term for the mask worn on stage by actors), but began, in the mid-20th century, to be applied more generally to virtually all forms of literature. It is particularly associated with the New Criticism which dominated Anglo-American criticism in the last century, although it has applicability as well to more recent approaches to literature. Broadly speaking, the concept of the persona makes a distinction between the "real" author of a work, and the particular voice and character that she or he may assume in his or her work. In some cases, the persona is evidently a fictional "personage," with a fictional history, identity, and views that may be very different from that of the author. In such cases, the effect of the persona is often ironic, in that it highlights the author's own misgivings about, or even disapproval of, what the persona represents or says. A classic instance of such an ironic persona is Swift's "Modest Proposer" in his A Modest Proposal, whose advocacy of cannibalism is clearly not Swift's own. In a broader sense, the persona can refer to the way in which an author fashions his or her own public literary voice to sound more convincing or "likable." Alexander Pope, for instance, very carefully managed his poetry to project the impression of a reasonable, moderate, good-humoured, and generally "Horatian" (i.e., modelled on the Roman poet Horace) character. While a persona employed in this way need not necessarily generate an impression of character that is very different from that of the actual, real-life author, it is still a deliberate construction intended to make the reader more susceptible to a particular message or meaning in the work. This use of the persona is related to the rhetorical notion of "ethical proof," whereby the author attempts to persuade the reader to a particular view by creating through language an apparently attractive and trustworthy "character" for himself or herself.

Monday, 10 September, 2012 Synecdoche ( s?'n?kd?ki ) — A synecdoche is a figure (closely related to metonymy) in which a more comprehensive term is used to describe a less comprehensive one, or vice versa. For instance, a part of something is used to refer to the whole (i.e., "arms" refer to the people he brought with him).

the whole of something is used to refer to a part (i.e., "university" stands in for the university committees or people responsible for imposing penalties):

its genus is used to refer to its class (i.e., the singular "gazelle" stands in for all gazelles):

its class is used to refer to its genus (i.e., the Bible is characterized by reference to all "books"):

Synecdoche is used a great deal in common speech and writing, and we are so attuned to it that we barely notice it when it appears. It is employed no less frequently in literature, where its effects may be more or less subtle, as in the case of Shakespeare's "Take thy face hence," from Macbeth. Often, however, it is used to produce something akin to surprise or shock, as in this instance from T.S. Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, in which "pair of ragged claws" stands in for the "whole" crustacean:

|

Fourth Wall — The "fourth wall" is a term used in theatre criticism, and refers to the

imaginary or notional "wall" that lies between the audience and the action on stage. The term is a relatively modern one,

and really makes literal sense only in the context of more modern "box" stages, in which the action occurs within a stage space bounded by one back and two side walls, and lies behind a framing

proscenium arch; the "fourth wall" would (if it actually existed) stretch across this arch. The theatres of the 16th and early

17th centuries did not feature prosceniums, and the stages themselves were often thrust out into the audience, with the

result that the action might be viewed from any number of angles around the stage; because of this, it was easier for the

actors to engage directly with audience members through asides or even direct address. The "box" stage configuration, however, more emphatically separates the audience from the action: the "fourth wall" signifies that distance.

Fourth Wall — The "fourth wall" is a term used in theatre criticism, and refers to the

imaginary or notional "wall" that lies between the audience and the action on stage. The term is a relatively modern one,

and really makes literal sense only in the context of more modern "box" stages, in which the action occurs within a stage space bounded by one back and two side walls, and lies behind a framing

proscenium arch; the "fourth wall" would (if it actually existed) stretch across this arch. The theatres of the 16th and early

17th centuries did not feature prosceniums, and the stages themselves were often thrust out into the audience, with the

result that the action might be viewed from any number of angles around the stage; because of this, it was easier for the

actors to engage directly with audience members through asides or even direct address. The "box" stage configuration, however, more emphatically separates the audience from the action: the "fourth wall" signifies that distance.