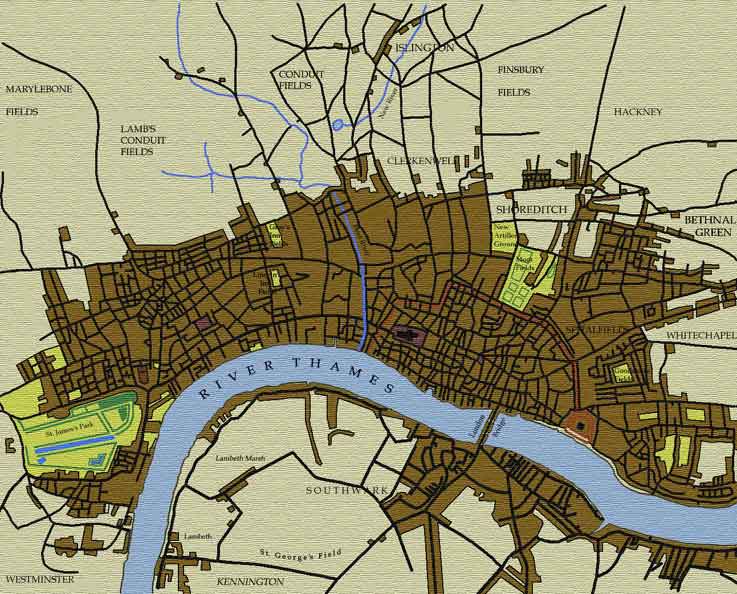

London ca. 1676

Covent Garden

|

Covent Garden was developed as a commercial enterprise

in 1631 by Francis Russell, the 4th Earl of Bedford, on land that had

been confiscated from the abbey of St. Peter at Westminster at the time

of the dissolution of the monasteries. (The name is, of course, a corruption

of "convent"; the piazza was built upon the site of the old

convent gardens). |

|

Intended as the centrepiece for a fashionable and

upscale residential neighbourhood, Bedford employed the foremost architect

of his day for its layout and design. Inigo Jones modelled the central

square upon the Italian piazza; its colonnaded design exhibits most obviously

the influence of the Italian architect Palladio. Jones surrounded the

square itself with arcades on two sides; at the west end sits his Tuscan-style

St. Paul's Church. In the streets immediately adjoining the square Bedford

had a number of graceful – and expensive – residential buildings

constructed; to service this new community, he issued licences for a fruit

and vegetable market, to be held in the centre of square. The entire development,

as originally laid out, covered approximately 40 acres. As intended, the new area rapidly

attracted further development, both in the form of new residential areas

associated with Bedford's development, and in the numerous high-end shops,

coffee-houses, and taverns that were soon opening near the square. By

the Restoration, Covent Garden was no longer on the periphery of London

development, as it had been when first constructed, but it was still,

by and large, an expensive area in which to live and shop. It is not coincidental

that the first theatres to built in the Restoration located themselves

near Covent Garden: quite aside from the area's convenience to both Court

and City, the area itself could boast a fair share of the fashionable,

theatre-going members of the public. Covent Garden represented, in fact,

a kind of centre-of-gravity for the "Town" and the Restoration

beau monde. John Strype noted in 1700 that the

area was "well inhabited by a mixture of nobility, gentry and wealthy

tradesmen . . . scarce admitting of any poor, not being pestered with

mean courts and alleys"; yet, by Strype's time, the area was already

undergoing a slow and painful transition. Ned Ward's London Spy,

published 1698-99, identifies the square – and St. Paul's Church

in particular – as a convenient rendezvous for married men and women

making assignations with lovers. More to the point, however, the fruit

and vegetable market established by Bedford had begun to affect the area

somewhat, attracting a crowd of increasingly less fashionable patrons.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Covent Garden area had become run-down,

and was better known for its prostitutes than for its fops. The magistrate

Sir John Fielding (brother of the novelist) lived in the area himself

in the mid-eighteenth century, and commented that "one would imagine

that all the prostitutes in the kingdom had picked upon the rendezvous." Covent Garden served as the hub of fashionable London for most of the Restoration, and its importance did not entirely diminish in the eighteenth-century, as it remained near the heart of the theatre district. Its design, construction, and management are also noteworthy in that they represented a radical departure from Tudor practice. In particular, the use of a communal square or piazza as the centrepiece for a new residential development, and the employment of uniformly designed facades for expensive row houses, anticipate common eighteenth-century practice. So too did the financing of the development by Bedford: most of London's expensive new residential developments would, in the eighteenth-century, be conceived as lucrative investments under the control of aristocratic landowners.

|

|

Website maintained by: Mark

McDayter

Website administrator: Mark McDayter

Last updated: April 25, 2002