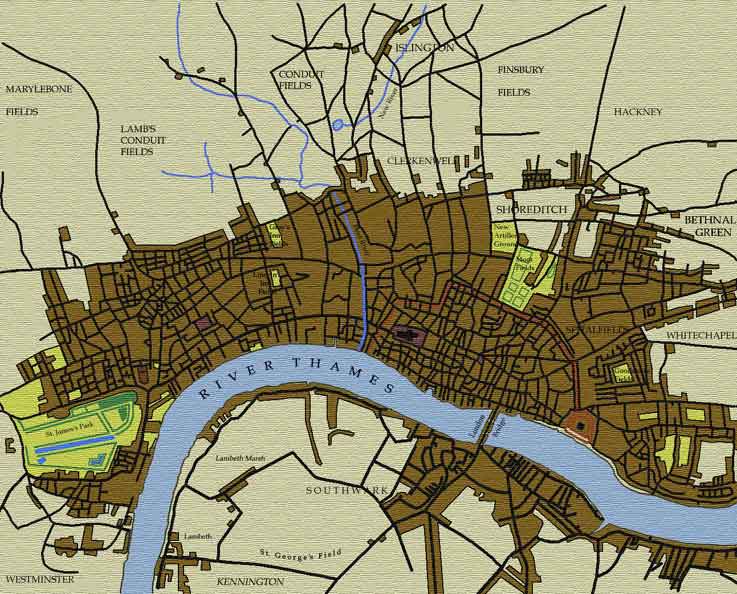

London ca. 1676

London Palaces

|

London and Westminster had, during the middle ages and Renaissance, been the site of a fair number of palaces, for royalty and others. By the Restoration, however, these had, for all intents, dwindled to three, two of which were royal palaces, and the third of which belonged the Archbishop of Canterbury. |

|||

|

James I, however, established Whitehall as the "home abode" of the monarchy in London. To ensure that his London residence properly reflected the magnificence of his reign, he commissioned Inigo Jones to design a magnificent new palace on the site; unfortunately, however, costs were prohibitive, and only parts of this were every actually constructed. Most important of these was the great Banqueting House, which was completed in 1622; its interior was embellished, in 1633 (during the reign of Charles I), by the addition of a magnificent painted ceiling, the work of Paul Rubens, and representing the apotheosis of James I. The Banqueting House was to assume a central role in the history of the Stuarts: it was in front of this building that Charles I was beheaded on 30 January, 1649, and it was from here that his son, James II, fled the country in 1688. Upon his restoration, Charles II adopted Whitehall as his London residence, and made such minor improvements as he could afford. It has frequently been noted that the rambling and confused layout of the palace both reflected and suited Charles' monarchical style: certainly, its main byways, alleys, and corridors proved convenient for his "backstairs" politics. Numerous Restoration satires make reference to the admission of his mistresses and "whores" through the many back doors and hidden entrances into his personal chambers here. Indeed, with the possible exception of St. James's Park, no London venue was more closely associated with Charles. The Palace had numerous outbuildings and attached features. A small but well designed garden looked out and across to St. James's Park; it was in this garden that the Earl of Rochester, during a drunken nighttime ramble with some friends, destroyed a glass chronometer that stood there. Additionally, the Palace boasted a small theatre, the Cockpit, designed by Inigo Jones and employed, in the reign of Charles I, for royal masques.

St.

James's Palace Following his defeat in the Civil War, Charles was imprisoned in St. James's Palace; it was here that he spent his last night before his execution before Whitehall on 30 January, 1649. It was also from St. James's Palace that the young prince, James, Duke of York (the future James II), escaped from Parliamentary custody on April 20, 1648; having been permitted to stay with his father during the latter's captivity, James made his way to the Continent, where he remained until 1660. At the Restoration, St. James's Palace became the primary London residence of the Duke of York; even following his accession to the throne in 1685, he retained his connections with his old home. It was here that his only son, the "Old Pretender" (as he was to become known) was born: some contemporary maps of the palace depict the possible routes by which the "changeling" child was allegedly conveyed into the Queen's apartments, hidden in a warming pan. William of Orange resided at St. James's Palace upon his arrival in London in 1688; upon his instillation as King William III, he and Queen Mary moved to Whitehall. This change in residence proved, however, temporary, for William was forced to return to St. James's Palace upon the destruction of Whitehall Palace by fire in 1698. Indeed, from that time, until the occupation of Buckingham Palace by the reigning monarch in the reign of George IV, St. James's Palace remained, in effect, the only London royal residence. Both King George I and George II had apartments here fitted out for their respective mistresses. In addition, a detached library, replacing an older one within the palace, was built by Queen Caroline, wife of George II, and finished in 1737. (The old library at St. James's was administered by Richard Bentley, and was the setting for Swift's The Battle of the Books ). Lambeth

House One of the more important components of Lambeth House is its chapel: here, traditionally, all Archbishops are consecrated (although there have, in practice, been exceptions). Previous to, and during, the Civil War, this chapel became a lightning rod for attacks upon the alleged "popish innovations" of Archbishop Laud: he was accused, for example, of having installed the stain glass in the chapel, although this was, in fact, medieval in origin. The chapel was, as a consequence, much damaged and defaced during the Interregnum. |

|

Website maintained by: Mark

McDayter

Website administrator: Mark McDayter

Last updated: April 25, 2002