|

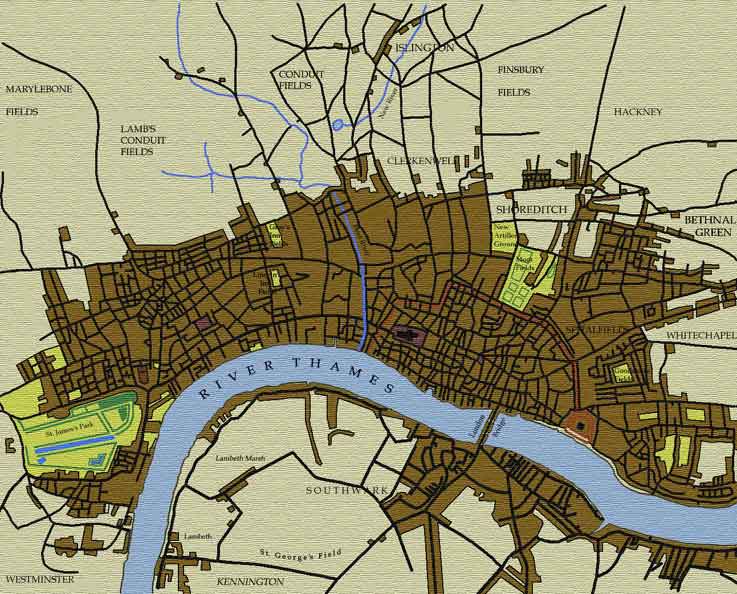

London was, amongst many other things, a city of

crime and poverty; it is not surprising, then, that its many prisons should

feature so prominently in the literature and literary history of the Restoration

and eighteenth-century. One important reason for this prominence is the

fact that a great many "offences" now not deemed to be so, or

not considered serious enough for imprisonment, could lead to incarceration:

bankruptcy, debt, and vagrancy are the most important examples. Given

that London abounded in all of these facets of life, the existence, by

1800, of no less than 18 prisons in London, serving a variety of clientele,

seems understandable.

|

|

Conditions in eighteenth-century prisons

were, by modern standards, horrendous: most prisons were filthy and overcrowded,

and little attention was paid to the welfare of the imprisoned. Drunkenness

and gambling were rife within the walls of these places, and violence

and disease took a terrible toll of the inmates. Of course, conditions

need not be so poor for those willing and able to supplement the jailor's

income with an unofficial stipend; ready money could buy a certain degree

of luxury. Extortion from jailors seems to have been customary, and the

experiences of Macheath, and venality of Lockit, in John Gay's Beggar's

Opera were probably the rule.

Bridewell

Built on the site of a Norman palace in 1523 as an appropriately magnificent

accommodation for the visiting Emperor Charles V, Bridewell was gifted

to the City by Edward VI in 1553; it was to serve as a workhouse for the

poor, and as a prison for vagabonds, prostitutes, disobedient apprentices,

and the generally indigent. Prisoners were employed picking oakum and

beating hemp. Ironically, the prison apparently began to attract the poor

from the areas surrounding London, who actually moved to the City in order

to take up residence in the institution. Alarmed, the citizenry of London

protested, and Bridewell began service instead as a storage house for

grain in the early seventeenth century. By the Restoration, however, the

building was once again being employed as a prison, and seems, again,

to have been reserved for prostitutes, the poor, and others whose sentences

were of relatively short duration. It was destroyed in the Great Fire

of 1666, and was rebuilt two years later in an even grander manner than

that of the previous edifice. Bridewell's prominent position in the daily

life of London is testified to by the frequency with which references

to the prison appear in the literature of the period; it also serves as

the setting for the fourth panel of William Hogarth's The Harlot's

Progress.

Newgate

Newgate Gaol (i.e., Jail) was originally housed in the gatehouse on the

London wall that went by that name, a function it had fulfilled since

at least the twelfth century; the gatehouse itself dated from the same

century. It was rebuilt in the fifteenth century (by the Lord Mayor, Dick

Whittington), and repaired in the mid-sixteenth and early seventeenth

centuries, only to be destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666. Rebuilt

in 1672, it was finally taken down in 1767. Newgate functioned as the

City's primary prison, and the original gatehouse seems to have been sufficiently

large for this purpose until the reign of Charles II; by the eighteenth-century,

however, the prison was terribly overcrowded. A magnificent and imposing

new prison, designed by George Dance the younger, was built between 1770

and about 1783; it was damaged during the Gordon Riots when it was attacked

by the London mob; it was finally demolished in 1902.

Conditions within this prison were, by all accounts,

terrible. Paradoxically, too, it was rife with crime: there were complaints,

for example, that forgers were at work within the actual prison walls

in 1669. The prison, it should be noted, was a frequent destination for

visitors to London, for one could pay for admission to view the condemned

within awaiting execution.

Fleet Prison

Although its origins are somewhat obscure, it is certain that the Fleet

Prison dates from at least Norman times. Destroyed in the Great Fire in

1666, it was rebuilt, only to be destroyed again in the Gordon Riots.

A reference to the prison in the London Gazette in January of 1671

suggests that this building contained about 150 rooms. Following the Gordon

Riots, it was rebuilt yet again in 1781-82.

Before the Civil Wars, the Fleet Prison seems to

have largely been reserved for those committed by the Court of the Star

Chamber, a prerogative court that was abolished just prior to the outbreak

of the First Civil War. From the Restoration, therefore, it was primarily

used as a debtors prison, and for bankrupts. It was certainly to this

capacity that the Fleet Prison owes most of its literary associations:

William Wycherley was imprisoned here for 7 years for debt; the early

eighteenth-century poets Elizabeth Thomas and Richard Savage served time

here as well for the same reason.

Gate House

Gate House lay near the west end of Westminster Abbey, and served as the

chief prison for the Westminster Liberties. Pepys was briefly imprisoned

here in 1690 upon suspicion of harbouring Jacobite sympathies.

Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell, or the "New Prison," was first established in the

seventeenth-century; it was rebuilt in 1775, and again in 1818. A fourth

prison on the site, dating from 1845-46, was finally closed in 1877.

|