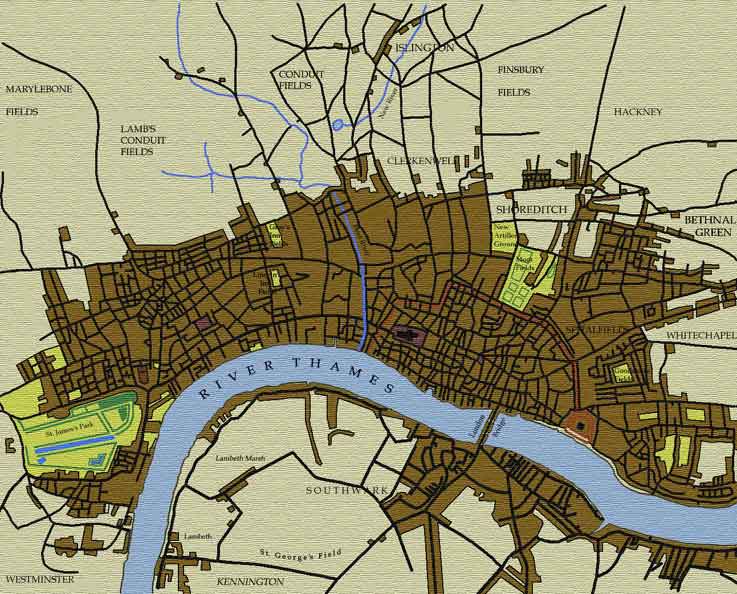

London ca. 1676

The City Walls

|

The Wall of London was itself of medieval construction,

although it followed quite closely the plans of the old Roman wall that

had surrounded Londinium, and was, in places, built upon the Roman foundation.

The medieval walls were 30 feet high, crenellated, and pierced by 7 gateways. |

|

Within the London Wall was the economic

heart of the City: here lay the financial institutions, liveried companies,

banking houses, and the Royal Exchange, all of which were the economic

engine that powered London and, indeed, all of England. In character,

London within the walls was primarily mercantile or financial, quite prosperous,

and strongly Nonconformist. The singularity of this character was responsible

for much of the historical friction generated between the City and the

Court. The City had long jealously guarded its ancient rights and prerogatives,

many of them dating from the middle ages. It had a history of wary and

occasionally hostile relations with the ruling monarch: it had, for example,

been the mainstay of opposition to Charles I during the Civil War, and,

with the development of the party system in the 1670s and 1680s, was strongly

Whig for the remainder of the century, and well into the eighteenth century. The City was punished for its support of Shaftesbury, Monmouth, and the Whigs in the "Tory Revenge," which was the aftermath of the exposure of the Rye House Plot and collapse of the Whig Exclusionists in 1682: the City's Charter — which guaranteed its ancient rights and privileges — was revoked, and Tory officers and administrators were imposed upon it by the King. Culturally it found itself under attack through much of the Restoration, as well: its commercial and dissenting nature made it a natural target for the drama of the age, dominated as it was by the patronage and tastes of the Town and Court. The burlesque "cit" from the City was a stock figure of the Restoration stage. In this regard, the dramatists were merely following the lead of the denizens of the beau monde, who were, for the most part, contemptuous of the City: the Frenchman Samuel de Sorbière observed that many of the inhabitants of the Town never entered the City at all. London within the walls was unusual in that its population was actually on a gradual decline throughout the period: there was a slow, but perceptible migration of its well-to-do inhabitants to the suburbs of the City, and to the fashionable West End neighbourhoods as these developed. This process was facilitated somewhat by the Great Fire of 1666, which destroyed most of the old City: the rebuilding was on a slightly more spacious scale, reducing the high population density somewhat, while many of the residents displaced by the Fire never returned. |

|

Website maintained by: Mark

McDayter

Website administrator: Mark McDayter

Last updated: April 25, 2002