Lec 9: Basic Navigation Concepts II

Today’s Lecture:

Basic Navigation Concepts (“Part II”) - from Locating a Distant Point

Announcements

Comments or Questions?

(General, Lab, Assignment, Readings)

Basic Navigation Concepts II

The Singapore 006 Airlines crash in

Taipei (Taiwan) in November 2000

Apparent Navigation error

Apparent Weather factor (typhoon)

(Relevance of the 2 Geography courses

on Navigation and Weather in the CAMP program?...)

Note also that Box 14.1 “Lost in

theFog” alludes to the hazard of airport ground navigation

Basic Navigation Concepts (“Part II”)

Locating a Distant Point

“What if you want to know the position

of something else (that’s not co-visible, eg. a rock-slide)”?

Done by

use resection to establish your

position

then use intersection to find the

position of something else

Note that

resection is based on backsights or

back bearings, while

intersections are made by foresights

or cross bearings

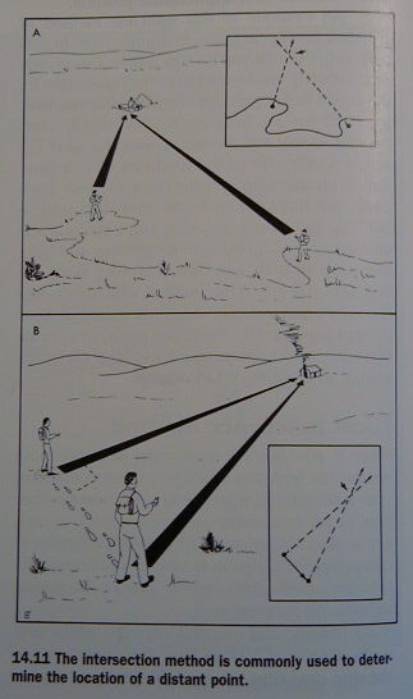

Using the intersection method you

sight on the unknown spot

from two ground positions whose map

positions are known

or can be

computed

the point at which these foresights

intersect establishes the feature’s location

As with resection three points are

better than two

because you get a triangle of error

to locate the distant point (from the

two or three ‘base’ points)

you can use similar techniques to

those discussed for establishing your own position:

inspection

method

compass method

radiobeacon

method

Inspection method

done as before but from two known

positions

Can also be done if there’s only one

known position:

perform the intersection for that

position

then measure distance and direction to

a second position

(and plot this

single-segment base line)

now perform the intersection for that

position

...and if you wish move on to a third

point

note that this method forms the basis

for the important traditional and once-popular

Plane Table

Mapping technique

Fig. 14.11

Compass method

same but with a compass instead of a

sight-rule

Radiobeacon method

navigation is undergoing a revolution

due to:

mobile radio transmitters and GPS

recently along with cell-phones

(What a potent

combination...!)

cf. the technologically advanced (but

economic failure) of the IRIDIUM system

Route-Finding Maps

The next challenge is how to use maps

to get from one location to another

Map user needs to choose the right map

or chart for the task

Land navigation

Water navigation

Air navigation

Land navigation

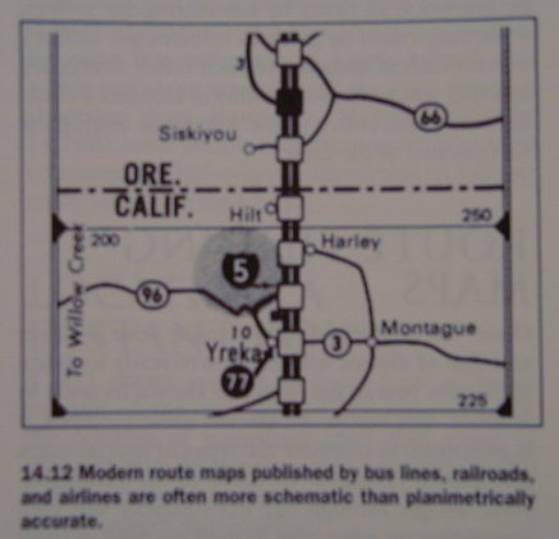

Peutinger tables: schematized (distorted) Roman maps

the tradition lives on, eg. in

Transportation maps

Fig. 14.12

“Strip” Maps, eg. AAA/CAA

Triptik maps

Fig 14.13 *** Triptik Image ***

Standard Road Atlas and Road Maps

***

Example: New York State ***

Modern Road Atlas

*** California Road Atlas (3 images)

***

The text recommends USGS Topo Quads at

the various scales:

DOQ,

1:24 000, 1:62 500

1:100 000, 1:250 000

1: 500 000, 1: 1000 000 (State map scales)

Heuristic: Always choose a larger-scale map, within reason

Water navigation

Nautical charts, Hydrographic charts

Q:

What’s so special about them?

Importance of special symbols

and the date of the chart

Air navigation

Aeronautical charts

Specially selected base map themes

and magenta-colored overlay of

aeronautical information

Example Images:

Aeronautical Chart

Sectional Chart Legend

Digital Aeronautical Charts

Upload to GPS

The date of the chart is usually given

in large red-type in the lower right margin

Route-Finding Techniques

aka Navigation

Moving effectively

through the environment

with the help of maps/charts and other

aids

Several methods:

Piloting

finding your way

by making direct reference to your surroundings

Dead Reckoning

you use distance

and direction logs, paying no direct attention to environmental features

In practice:

many variations of each

that serve to

blur a clear-cut distinction

and in effect,

lead to a plethora of hybrid methods

Navigation involves two

stages/activities

plan the route

including

alternate routes!

execute the route

maintaining your

route in the field

Question: What’s a possible third activity?

A:

Debriefing

a “post mortem” of the navigation

exercise

Planning and executing navigation

using the two main methods

Piloting

based on the use of environmental cues

Planning for piloting

use navigational marks (landmarks,

skymarks, seamarks)

must be co-identifiable in reality and

on the map

vision, sound

smell, tactual (eg. marsh, bog, wetland)

Computer aids to piloting planning

Route-finding software

(also discussed

in Ch. 9: Software for Map Retrieval)

Traditional Piloting Planning

A distinction is made between

different types of areas:

wilderness

rural

urban

Use of aids

buoys, beacons

radio transmitters, satellites act as

supplements, e.g. to contact flying

planning involves

thinking/reflecting over the route

and especially clarifying obscure

segments

tip:

follow a well-defined path

the metaphor of a “hand-rail”

e.g. flying

along a road

pre-trip planning may also involve

making computations and plotting a

course in tricky areas

and taking the information

(preferrably in the form of marked map) along

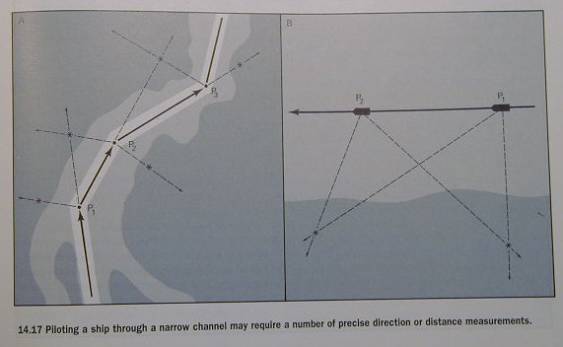

An example is shown in Fig. 14.17

Piloting a Course

Driving a car in town is piloting

and often we are unaware of the fact

we are piloting

however, sometimes a familiar setting

can become functionally unfamiliar (fog, snow,darkness)

If visibility is (near) zero - don’t

move!

Vehicle piloting systems

for when you are moving through less

or unfamiliar territory

use Electronic Positioning systems as

aids

modern development: moving map displays

where electronic

positioning devices update the position of a cursor on the map

Electronic positioning systems

Inertial navigation systems

drawback -

accumulates error

Signal dependent systems (eg.

radionavigation, GPS)

advantage: do

not accumulate error

GPS is becoming ubiquitous:

“I am the pilot of my garbage truck”

GPS w/out GIS is

used extensively by vehicle fleets

such as recycling companies

there is a wide

array of trip planning and routing products on the marketplace

Traditional Piloting Procedures

Personalize your map (eg. with

highlighters, pencil)

Use your map constantly to track your

progress

frequent map

checks or orientation stops

Beware of mental maps of

direction-givers

When there are few or no environmental

cues

an alternative to piloting is needed

Dead Reckoning

Based on keeping track of distance and

direction traveled from the starting point

“To determine your position, you must

know

either the

direction and distance you’ve travelled,

or the

direction, speed and time that has elapsed since you have started out”

Errors will accumulate

dead recknoning is not as accurate as

piloting

therefore done as a last resort

or to augment

piloting

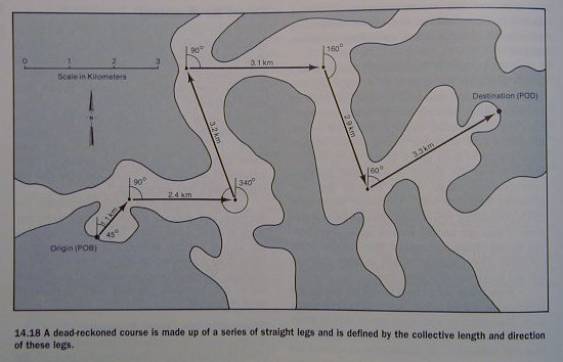

Planning for dead reckoning

Step 1

construct a plot of the desired course

made up of a

series of segments or “legs”

from the POB

(point of beginning) to the POD (point of destination)

Fig. 4.18

Step 2

measure and record the direction and

distances of each segment

in a manner suitable and convenient

for use in field conditions

to preempt the necesity to do

conversions in the field

eg. use absolute direction readings,

such as Grid North

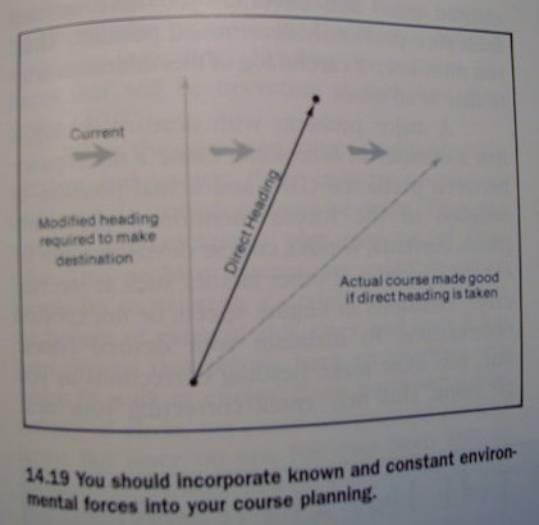

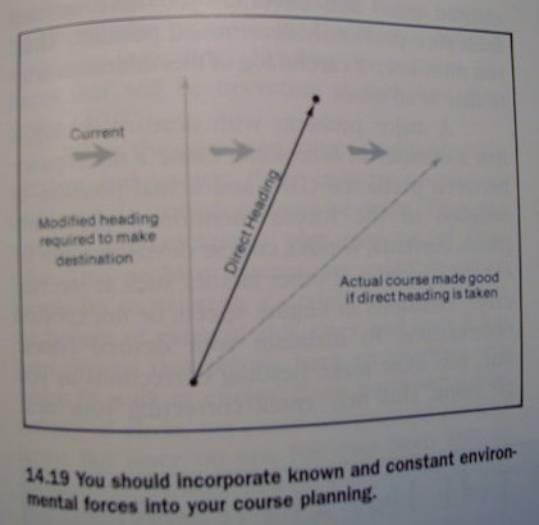

incorporate known and constant forces

as modifications (eg. wind)

Fig 14.19

Time is an important aspect of dead

reckoning

it is advisable to use travel-speed

and course length

to compute

estimated passage (or transit) time (Table 14.3)

and ETA or ETD

(estimated time of departure)

Executing a dead-reckoned course

Consists of of taking and recording

distance and direction data

plotting it down

and comparing it

to the planned course

This applies whether it’s a strictly

manual procedure

or if automatic dead reckoning

equipment is used

Inertial navigation equipment is

heavily used

but not always fool-proof

cf.

Box 14.3: KAL flight 007 from

Anchorage to Seul.

Manual dead reckoning procedures

performed in the field based on

direction and distance,

where distance

is measured by (speed x elapsed time)

must be

carefully logged

discrepancies will occur between

planned DR position and actual position

and corrections must be constantly

made

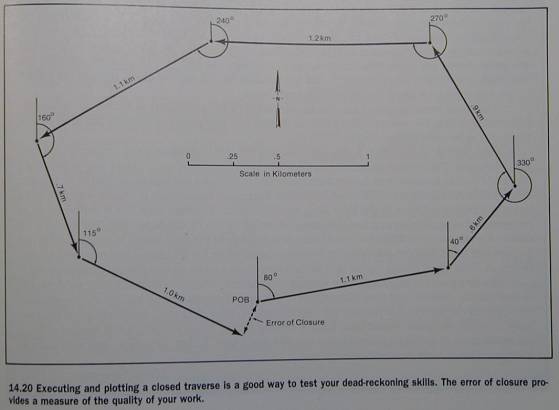

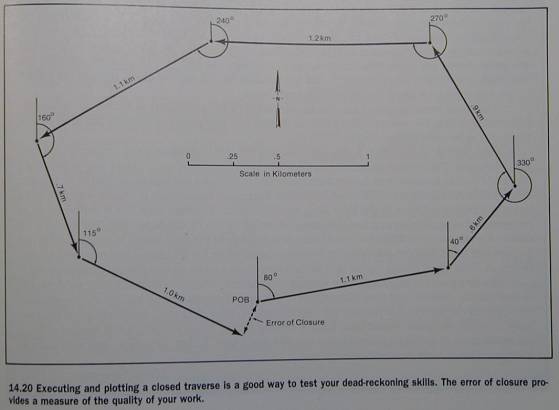

a closed traverse is used to practise

dead reckoning

Fig. 14.20

the gap between planned destination

and actual destination

is known as closing error (or error of

closure)

in practise a mix of dead reckoning

and piloting is used

Practical Navigation

the navigator’s rule is “anything

goes”:

use all methods you can to get there

from here...

mix methods of navigation

and switch between methods as the

need/opportunity arises

‘til next week!