URL: http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/v408/n6814/full/408758a0_fs.html

Date accessed: 06 February 2001

Nature 408, 758 (2000) © Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

![]() 14

December 2000

14

December 2000

PAUL SMAGLIK

[WASHINGTON]

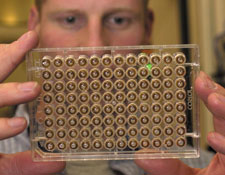

Testing times: centres will soon be deciphering small genomes alone. Leaders of US sequencing centres have described the fragmentation of the

consortium as inevitable — especially as the group nears its goal of

publishing a draft version of the human genome. But other researchers wonder if the consortium is breaking up prematurely.

They believe a historic opportunity has been lost to build and maintain a

distinctively collaborative approach to genomics. Most of the human genome was sequenced at four centres in the United States

and one in the United Kingdom. But many other universities and centres in

America, Europe and Japan also took part. The links between the partners have

been breaking up more rapidly than some of them had hoped. Ironically, one of the things driving the sequencers apart is the

whole-genome shotgun sequencing technique that once brought them together. The

announcement in 1998 by Celera Genomics, based in Rockville, Maryland, that it

would use the technique to sequence the human genome before the HGP, helped to

galvanize the publicly funded consortium. Whole-genome shotgun sequencing lends itself to a centralized approach, as

any facility with enough sequencers can break the genome into millions of

pieces, read them and reassemble them. In contrast, the HGP divided the genome

into small segments, assembling the pieces soon after they were read. The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) tacitly acknowledged the merits of

Celera's approach when it revised its plans to sequence the mouse. Initially,

the NIH considered applying the same clone-by-clone technique used by the HGP.

But the National Human Genome Research Institute has decided instead to sequence

most of the mouse genome by the shotgun method, using the clone-by-clone

approach only to build a map to help piece the shotgun data together.

Gene shift: Lander says partners will compare notes, not share

projects. Richard Gibbs, director of the sequencing centre at Baylor College of

Medicine, Houston, says that the loosening of the consortium was inevitable. But

he thinks this is happening too quickly. "It makes most sense to enjoy the

fruits of its efficiency as long as possible," he says. Bob Waterston, however, director of the sequencing centre at Washington

University in St Louis, says that working alone makes projects easier to manage. Eric Lander, director of the Whitehead Institute at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, does not foresee the consortium disbanding completely.

Instead, he suggests it will move from sharing projects to discussing the merits

of different sequencing strategies and technologies.

The cooperation that characterized the international Human Genome Project (HGP)

is shifting rapidly towards competition as the project's members vie to decipher

the genetic codes of other species.

AP

The validation of Celera's technique — and the build-up in the number of

sequencing machines at each major centre to prevent Celera from taking the lead

— means that individual centres will soon be able to decipher small genomes on

their own. The UK Wellcome Trust's Sanger Centre, near Cambridge, is taking on

the zebrafish genome alone (see Nature

408, 503; 2000), and the US Department of Energy's Joint Genome

Institute in California sequenced 15 bacterial genomes in an October

"Microbial Marathon" that also served, in effect, as a declaration of

independence.

SAM

OGDEN

Categories: 16. Economics and Biotechnology, 32. Genome Project