URL: http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/v409/n6822/full/409769a0_fs.html

Date accessed: 25 February 2001

Nature 409, 769 (2001) © Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

![]() 15

February 2001

15

February 2001

HORACE FREELAND JUDSON

Biologists must take

responsibility for the correct use of language in genetics.

We think we think with words: too often, the words think us. Four centuries

ago, Francis Bacon showed us how those who say they seek knowledge are prisoners

of language. He proposed the doctrine of the four idols objects of false

worship that block our understanding. Of these four Bacon wrote: "The Idols of the Tribe lie deep in human

nature. . . The human understanding . . . readily supposes a greater order and

uniformity in things than it finds . . . [it] is infused by desire and emotion,

which give rise to 'wishful science'" and attachment to preconceived ideas.

The Idols of the Cave are your particular set, or my different one, of

preconceptions and prejudices. The Idols of the Theatre are those "which

have crept into human minds from . . . faulty demonstrations"

experiments. They distort understanding because they take the representation for

the reality. Then, worst, "There are also idols arising from the dealings

or associations of men with one another, which I call Idols of the

Market-place". He had in mind, evidently, the agora, where in

ancient Athens men met to talk. "For speech is the means of association

among men," he wrote, "and in consequence, a wrong and inappropriate

application of words obstructs the mind to a remarkable extent." Bacon's terminology is unfamiliar, yet his formulations cut across recent

fashions of thought and jolt us out of our preconceptions. The language we use

about genetics and the genome project at times limits and distorts our own

understanding, and the public understanding. Look at the phrase or marketing slogan 'the human-genome project'. In

reality, of course we have not just one human genome but billions. At the level

of genes, the project promises a useful consensus, but at the level of sequences

of nucleotides variability is great and important, and not just for uniquely

identifying rapists and murderers. Clues to disorders, to talents and even to

human origins may be buried there. Further, the genome project draws in various

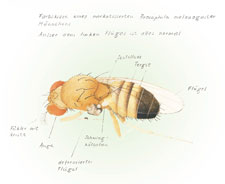

bacteria, yeast, nematode, fruitfly, zebrafish, mouse and chimpanzee.

Comparisons are already forcing attention to features of the sequences

previously unrecognized but so essential they have been conserved over hundreds

of millions of years of evolution. Then, too, the entire phrase the

human-genome project: singular, definite, with a fixed end-point, completed by

2000, packaged so it could be sold to legislative bodies, to the people, to

venture capitalists. But we knew from the start the genome project would never

be complete. The maps, or the sequences, are just the start of many lines of

research, polyphiloprogenitive, multiply multiple genome projects. This sloppy language is not merely shorthand, scientists talking among

themselves. Scientists talk to the media, then the media talk to the public

and then scientists complain that the media get it wrong and that politicians

and public are misinformed. What the media do is mediate. Public misinformation

is largely and in origin the fault of scientists themselves. Bacon also said:

"Words turn back and reflect their power upon the understanding." The phrases current in genetics that most plainly do violence to

understanding begin "the gene for": the gene for breast cancer, the

gene for hypercholesterolaemia, the gene for schizophrenia, the gene for

homosexuality, and so on. We know of course that there are no single genes for

such things. We need to revive and put into public use the term 'allele".

Thus, "the gene for breast cancer" is rather the allele, the gene

defect one of several that increases the odds that a woman will get

breast cancer. "The gene for" does, of course, have a real meaning:

the enzyme or control element that the unmutated gene, the wild-type allele,

specifies. But often, as yet, we do not know what the normal gene is for.

The fruitfly: Drosophila mutants are a cornerstone of the

language used in genetics. Morgan and his group themselves understood what the language meant. At that

time, a number of scientists were still intensely sceptical of mendelism. They

did not believe in genes. In 1917, Morgan published an extended reply to these

foes. This was just seven years after he had announced the discovery of the

first mutant fruitfly a male with white eyes instead of the normal red

and with it had demonstrated what we now call sex-linked inheritance. "There are several reasons why we need the conception of the gene,"

he wrote. In the first place, each gene has manifold effects. "If we take

almost any mutant race" or 'strain' as we would now say "such

as white eyes in Drosophila, we find that the white eye is only one of

the characteristics that such a mutant race shows." Further, Morgan wrote,

although traits may vary, "there is at present abundant evidence to show

that much of this variability is due to the external conditions that the embryo

encounters during its development. Such differences as these are not transmitted

in kind they remain only so long as the environment that produces them

remains." Pleiotropy. Polygeny. Perhaps these terms will not easily become common

parlance; but the critical point never to omit is that genes act in concert with

one another collectively with the environment. Again, all this has long been

understood by biologists, when they break free of habitual careless words. We

will not abandon the reductionist mendelian programme for a hand-wringing

holism: we cannot abandon the term gene and its allies. On the contrary, for

ourselves, for the general public, what we require is to get more fully and

precisely into the proper language of genetics.

Our thinking about genes in this way has a strong historical origin. In 1913,

Alfred Sturtevant, a member of Thomas Hunt Morgan's fly group at Columbia

University, drew the first genetic map "The linear arrangement of six

sex-linked factors in Drosophila, as shown by their mode of

association". Ever since, the map of the genes has been, in fact, the map

of gene defects. Only about fifteen years ago, when DNA sequencing and the art

of locating genes on chromosomes began to be practical, were geneticists able to

isolate a gene sequence and then reason forward to what it specifies.

CORNELIA

HESSE HONEGGER/PRO LITTERIS

Category: 4. Ethical and Social Concerns Arising out of Biotechnology, 32. Genome Project and Genomics