What a long, strange trip

it's been. . .

URL: http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/v409/n6822/full/409756a0_fs.html

Date accessed: 25 February 2001

Nature 409,

756 - 757 (2001) © Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

15

February 2001

15

February 2001

The draft human genome

sequence published in Nature this week is the culmination of 15 years of

work, involving 20 sequencing centres in six countries. Here, we present a

reminder of some of the key moments.

1985

In 1985, Charles DeLisi, then associate director for health and environmental

research at the Department of Energy (DoE), begins to discuss a mammoth project

— of a scale unprecedented in biology — to sequence the complete human

genome. DoE funding begins in 1987.

1988

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) establishes the Office of Human Genome

Research in September 1988. Renamed the National Center for Human Genome

Research (NCHGR) a year later, its director is James Watson, co-discoverer of

the double helix structure of DNA. Watson's testimony to the US Congress, in

which he pledged to devote a small fraction of the project's budget to 'ethical,

legal and social' issues, had proved instrumental in garnering political

support.

Early 1990s

With sequencing still slow and expensive, the genome projects adopts a

'map-first, sequence-later' strategy. In the early 1990s, two Parisian

laboratories, the Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain and Généthon, have an

integral role in mapping — underlining the project's international character.

The labs' driving forces are Daniel Cohen (top) and Jean Weissenbach. Later, the

genome project constructs a higher-resolution map that is used to sequence and

assemble the human genome.

1992

Francis Collins of the University of Michigan replaces Watson as head of NCHGR

in April 1992. Watson had earlier clashed with Craig Venter, then at NIH, over

the patenting of DNA fragments known as expressed sequence tags.

1992

Later that year, Venter sets up The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) in

Rockville, Maryland. TIGR later sequences a host of bacterial genomes, starting

with Haemophilus influenzae.

1996

In February 1996, at a meeting in Bermuda, international partners in the genome

project agree to formalize the conditions of data access, including release of

sequence data into public databases within 24 hours. These came to be known as

the 'Bermuda principles'.

1998

In May 1998, Venter forms a company to sequence the human genome within three

years. The company, later named Celera, will use an ambitious 'whole genome

shotgun' method, which involves assembling the genome without using maps. But

its data release policy will not follow the Bermuda principles.

1999

The public project responds to Venter's challenge. By early 1999, it is on track

to produce a draft genome sequence by 2000. Increasingly, the bulk of the

sequencing takes place in five huge centres: at the Whitehead Institute for

Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Sanger Centre near

Cambridge, UK; Baylor College of Medicine in Houston; Washington University in

St Louis; and the DoE's Joint Genome Institute (JGI) in Walnut Creek,

California. The centres' leaders are dubbed the 'G5'. Here, Robert Waterston of

Washington University in St Louis and John Sulston of the Sanger Centre are

pictured in a rare moment of relaxation, while Trevor Hawkins and Elbert

Branscomb of the JGI prepare samples.

1999-2000

The first complete human chromosome sequence — number 22 — is published in

December 1999. Chromosome 21 follows in May 2000, a collaborative effort led by

German and Japanese groups under the direction of André Rosenthal and Yoshiyuki

Sakaki, respectively. Sakaki (centre) is pictured here at Nature's

chromosome 21 press conference in Tokyo.

2000

On 26 June 2000, leaders of the public project and Celera announce completion of

a working draft of the human genome sequence. Collins and Venter are seen here

on television with Ari Patrinos of the DoE, who cut through the animosity

between the rival projects to broker the joint announcement at the White House

in Washington.

Outside, celebrations continue with Eric Lander of the Whitehead Institute,

Baylor's Richard Gibbs, and Waterston and Richard Wilson from Washington

University.

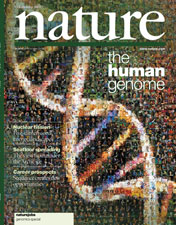

This week

Finally, this week sees the publication of the draft genome, the public sequence

in Nature, Celera's in Science.

Super models

The complete genome sequences of model organisms are proving immensely valuable

to biologists working on these species, and will also help interpret the human

genome sequence. Published highlights to date include the yeast Saccharomyces

cerevisiae (May 1997), the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (December

1998), the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster (March 2000, right), and the

plant Arabidopsis thaliana (December 2000, left).

Technical gurus

Without advances in sequencing technology, we would still be waiting to unveil

our genetic blueprint. Double Nobel laureate Fred Sanger (pictured) of the

Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge invented the basic technique of

gene sequencing back in the 1970s. In the 1980s, Leroy Hood, then at the

California Insitute of Technology in Pasadena, introduced the first automated

sequencing machine. But it was the ABI PRISM 3700 DNA Analyzer, developed by

Michael Hunkapiller of PE Biosystems, which allowed the rapid sequencing

progress made by both Celera and the public project over the past two years.

Assembling fragments of the genome into a complete sequence, meanwhile, depended

heavily on computer programs developed by Philip Green of the University of

Washington in Seattle.

We are grateful for contributions and input from Francis Collins, Richard

Gibbs, Victor McKusick, John McPherson, David Stewart and the staff of the Cold

Spring Harbor Laboratory.

PHOTOGRAPHY IN THIS ARTICLE: PETER MENZEL/SPL, STEVE MUREZ/RAPHO/NETWORK,

CHRISTIAN VIOUJARD/FRANK SPOONER, RAPHAEL GAILLARDE/FRANK SPOONER, ROBERT

HARDING, J. BERGER/T. LAUX/E. MEYEROWITZ, LIAISON, NIKKAN KOGYO SHIMBUN, JAMES

KING-HOLMES/SPL.

Nature

© Macmillan Publishers Ltd 2001 Registered No. 785998 England.

Nature

© Macmillan Publishers Ltd 2001 Registered No. 785998 England.

Category: 32. Genome

Project and Genomics

![]() 15

February 2001

15

February 2001