|

1 BACON Preface to The great instauration; The new organon, Aphorisms

1-46; selections

from The advancement of learning (The Works of Francis Bacon, James Spedding, Robert Ellis, and Douglas Heath, eds. 14

volumes (London: Longman, 1858-1874), vol. IV, pp. 13-17,

20-27, 47-57, and 294-98)

There are a couple of

reasons why this rebirth occurred when and where it did. One is that early modern People in the Ancient

world lived behind what historians of technology have described as an energy

bottleneck. The amount of energy

available to them from plants, animals, and their own labour was too little

to allow them to readily produce yet more energy. Consequently, they believed that there are definite, and very short limits to what they could do to

control the forces of nature or improve the conditions of their lives. Consider, by way of example, the following

passage from the Roman poet, Lucretius, writing in the first century CE, at a

time when the period of ancient philosophy was drawing to a close: Quis regere

immensi summam, quis habere profundi indu manu

validas potis est moderanter habenas, quis pariter

caelos omnis convertere et omnis ignibus aetheriis

terras suffire feracis, omnibus inve

locis esse omni tempore praesto? Who could rule the whole of the

universe? Who could hold in coercive hand the

strong reins of the unfathomable? Who could spin the firmament and

ferment with the fires of ether all the fruitful earths? Who could be in all places at all

times? [De

rerum natura II

1095-1099] Lucretius’ unspoken

answer to this question was that no one could do these things — not even the

Gods. This last idea, that not even

the Gods could intervene in the course of nature, was a minority view at the

time, but it gave all the more eloquent expression to the view that mere

human beings are certainly incapable of intervening in the course of nature

to improve their circumstances. By the beginning of

the early modern period this outlook on the amount of power within our grasp

had begun to change. The energy

bottleneck had been traversed, first by water mills, which came to be widely

employed in feudal times, and then by wind mills, which by the fourteenth

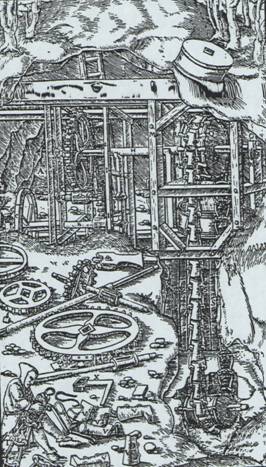

century were able to produce energy equivalent to 20-30 horsepower. During the middle ages and the Renaissance

a number of other inventions and discoveries had been made that had

significantly improved the material conditions of life and given people far

greater control over their circumstances: galleys that did not need to be

rowed by slaves and that could harness enough wind energy to sail even though

outfitted with heavy cannon; gunpowder to fire the cannon and to use in

mines; the magnetic compass, which allowed people to sail out of sight of land;

the mechanical clock; and the printing press, to name some of the most

important. Accordingly, when we

look at the works of an early modern thinker like Francis Bacon, we find a

more optimistic attitude about the potential for human beings to acquire the ability

to intervene in the course of nature.

[We] ought on the contrary

to be surely persuaded of this; that the artificial does not differ from the

natural in form or essence, but only in its efficient [cause]. Since [we] have no power over nature except

that of motion, [we] can put natural bodies together and can separate them,

and therefore wherever the case admits of the uniting or disuniting of

natural bodies by joining (as they say) actives with passives, [we] can do

everything. [Works IV 294] Interestingly, there

is nothing new to the conception of the nature that Bacon was giving voice to

here. It is shot through with ideas

and distinctions drawn from ancient, and

particularly Aristotelian philosophy.

Bacon’s distinction between “the artificial” (that is, what is made by

human beings) and “the natural” is Aristotelian, as are his notions that

these things are characterized by a “form” or “essence” and that they are

brought into being by “efficient causes.”

So also is his notion that the reason things change is because bodies

with a certain “active potency” to transmit a form (“actives” as Bacon called

them) have come into contact with bodies with a certain “passive potency” to

receive that form. But while the theory

of nature that is expressed by this text is very old, the optimism it

expresses about human abilities to intervene in the course of nature was

quite new. There is a hint here that

we might be able to do anything — even “control nature in action,” as Bacon

put it elsewhere — if only we could discover what “actives” to move into

contact with what “passives.” Of

course, this presumes an ability to mine “actives” and “passives” and to move

them appropriately. But the

technological innovations of Bacon’s day made him think that there was no

longer an obvious limit to the extent of our power to mine, smelt, and move

materials. New machines were giving us

new powers, and those new powers were making it possible to make yet stronger

machines that would give us yet greater powers. Bacon wanted knowledge and philosophy to

become like mechanics: to yield inventions that would produce yet more

knowledge, setting them on an ever-increasing path of development. At the same time that

Bacon was convinced that there is more knowledge to be gained, he was also

led to make a very different assessment of the worth and nature of knowledge

than any that had been expressed in the centuries before him. The ancient pessimism about our ability to

intervene in the course of nature had led people to suppose that even if we

could come to understand what makes things happen in nature, this knowledge

would be largely useless. Not

possessing the energy to intervene in the course of nature, the best

knowledge could give to us would be some ability to predict what would happen

next, not an ability to prevent it. Not surprisingly,

those ancients who valued knowledge found it valuable for other purposes than

those of gaining control over nature.

Plato and Socrates supposed that wickedness and evil are products of

ignorance of the ultimate consequences of our actions, so that no one could

knowingly do wrong. For them,

knowledge would make us virtuous and honourable. Aristotle supposed that the very essence of

humanity involves rationality, so that we can only be truly happy when

fulfilling this end and living a life of quiet contemplation. Lucretius maintained that knowledge of the

workings of nature would teach us that not even the Gods can do anything to

change the course of nature. In

learning this, we would be freed from superstitious fears and would acquire a

sort of peace of mind that would enable us to live happy and blessed lives. And the Stoics supposed that knowledge of

the workings of nature would help us appreciate the inevitability of things

and see how even our own misfortune is part of an inexorable development

towards the greater good. This

knowledge would reconcile us to our fate and make us better able to endure

adversity. In sharp contrast to

these assessments of the practical worth of knowledge in making us better,

happier, more self-reliant, more honourable, and better able to endure

adversity, Bacon thought that the proper end of knowledge is to show us how

we can transform nature so as to improve the material conditions of

life. As he put it, the proper goal of

knowledge is to “command nature in action” and come up with “inventions” that

can “in some degree overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity” (Works

IV p.27). Looking back at the

philosophy that had preceded him, and seeing how little it had managed to do

in this regard, he charged that the ancient and medieval tradition

represented the “boyhood” of human knowledge, and had the characteristic

property of boys: it could talk (produce thick volumes of incomprehensible

jargon), but it could not reproduce (Works IV p.14). And he even compared moral knowledge

unfavourably to practical knowledge, observing that, according to accepted

Christian mythology contained in the Book of Genesis of the Bible, it had

been the pursuit of moral knowledge (of good and evil) that had gotten Adam

and Eve expelled from the Garden of Eden, not the pursuit of practical

knowledge (represented by Adam’s activity of classifying and naming the

species of living things). For Bacon, any

knowledge worthy of the name ought to be useful for producing something. It ought to show us how to invent machines

and devices that improve the material conditions of our lives. Most importantly, it ought to generate new

knowledge and works and inventions that put us in a position to invent and

produce yet more powerful or yet finer instruments and devices. But Bacon’s

comparatively traditional physics of “actives” and “passives” (alluded to

above) also has implications for how one is to go about getting this

knowledge. The kind of knowledge he

wanted, knowledge that gives us power over nature, is knowledge of what

“actives” to combine with what “passives” in order to produce change. The trouble is that when an active is

combined with a passive, the change is brought about by nature “working

within,” as Bacon put it in Aphorism IV of the New organon. We usually cannot isolate what it is in the

actives and passives that makes the change occur (what Bacon called the “latent constitution” of objects and

“latent processes” they perform).

Not being able to see the small mechanism responsible for the change,

we are in no position to tell in advance, just by looking at different kinds

of material, what kinds of change they will produce in combination. We have no choice but to make the

experiment of actually combining them, in various proportions and under

various circumstances, and seeing what will happen. This meant that Bacon

was thrown back on the use of essentially the same scientific methodology

that Aristotle had used: a method of what is called resolution and

composition (or induction and deduction or analysis and synthesis). The method is fundamentally empirical or

experimental. It requires that we go

out and observe nature, combining different substances in all sorts of

different ways, in order to see what changes result. This investigation would hopefully put us

in a position to move, by a process of what was variously called “induction”

or “analysis” or “resolution” from a study of particular events to a

discovery of general laws governing those events. It would also put us in a position to

identify which objects are “active” in which ways and which are “passive” in

which ways and to move from a study of these macroscopic objects to a theory

of the underlying “latent constitution” and “latent processes” in the actives

and passives responsible for making the change occur. Once having done this, we would be in a

position to move on to the second stage of the method, the stage variously

referred to as “deduction” or “synthesis” or “composition.” In contrast to the first stage, which

proceeds from the “bottom up,” as it were (from sense experience of particulars

and events to general theories about what particulars are made of and what

causes change), this stage moves from the “top down” (from general theories

back to particular facts). It appeals

to general rules and principles both to explain why what is happening is

happening and to predict what will happen next. However, while Bacon

had essentially the same picture of how we must proceed to build up a system

of knowledge or science or philosophy (at the time these were all the same),

he differed with Aristotle over a number of details. These differences are examined in the notes

that follow. QUESTIONS ON THE

1. What did

Bacon mean by comparing the wisdom of the ancients to the boyhood of

knowledge?

2. How is it

that the mechanical arts are superior to philosophy?

3. How did

Bacon respond to the charge that the works of the ancients have withstood the

test of time, and that if more could have been done

to improve the sciences it would have been done already?

4. How did

Bacon respond to the charge that the pursuit of knowledge of nature may be

impious and contrary to divine commands?

5. What are

the true ends of knowledge?

6. What was

the chief effect Bacon took the new science he was proposing to promise?

7. What is the

proper method to pursue when inquiring into the nature of things?

8. How does

the type of induction Bacon recommended differ from traditional forms of

induction?

9. What is the

key to rectifying the defects of sense experience, according to Bacon? 10.

What is the “fixed and established maxim” that

we must not forget on pain of being seduced by the insidious action of

ineradicable idols? NOTES ON THE In the selections

assigned for reading, we see Bacon offering three principal objections to

Aristotelian philosophy and science. A

fourth is not mentioned but will be discussed here as well. The first three objections concern the

Aristotelian approach to induction, the fourth concerns the Aristotelian

approach to deduction. •

The Aristotelians had wrongly placed an

implicit trust in their senses, when in fact the evidence of sense needs to

be “sifted and examined” (the way we pan gold at a river bed, where most of

what the river gives to us is not worth much) •

The Aristotelians had based their general

theories on a hasty induction, drawn too quickly from too few experiences,

and had focused on the wrong sorts of experiences (experiences of what is

“naturally” or normally the case as opposed to experiences of what is

preternatural, that is, uncommon, and experiences of what is constructed by

human craft) •

The Aristotelians had arrived at the wrong

general theory of the latent constitution of things and the latent processes

between things (one proven false by the fact that it has failed ever since

Aristotle to yield new knowledge or new inventions that might improve the

material conditions of life). This is

the theory that change is ultimately due to the contact and reaction of

active and passive potencies or forms in things. Bacon thought that a more thorough

examination of the evidence would lead to a deeper account of what latent

constitution makes “actives” active and “passives” passive. This theory would have more in common with

what had been thought by the ancient atomist philosophers, who had attempted

to account for all change as a consequence of the motion of differently

shaped particles. (This is the feature of Bacon’s critique that does not come

up in our readings) •

Having arrived at an incorrect general theory,

the Aristotelians had given that theory a specious appearance of truth by

relying on syllogistic logic to deduce consequences from the theory. But syllogistic logic does not allow us to

discover new truths. It only allows us

to draw out consequences already contained in the general rules and

principles we have previously accepted as premises. The adequacy of a system of knowledge

cannot be judged by its success as yielding these sorts of question-begging

results. It needs to be judged by

whether it leads to progress and improvement. In seeking to rectify

these inadequacies, Bacon developed three boldly original new notions, the

notion of a controlled experiment, the notion of a crucial experiment or

“cross instance” and the notion of a collaborative research institution. He also developed an account of “idols” or

false inclinations of the understanding.

He was highly celebrated by later philosophers on account of these

inventions. Trust

in the senses and controlled experimentation. I mentioned earlier that the early modern

period was a time of religious upheaval and reformation. In challenging the authority of the

established church the reformers had recovered and revived the works of the

ancient Greek sceptical philosophers, work that they saw as contributing to

the point that no one is in a position to set themselves up as an authority

in matters of religious knowledge and that toleration for how things appear

to each individual needs to be exercised.

Bacon, who was at one point the Prime Minister of England, a “half

reformed” country (it had thrown off submission to the authority of the Pope,

but its national church continued to contain many features that the reformers

objected to, such as an ecclesiastical hierarchy and prescribed ritualistic

forms of worship), serendipitously (or, not surprisingly) proposed a middle

way between the position of the Aristotelians and the sceptics. Following the sceptics, Bacon denounced the

Aristotelians for uncritically relying on sensory experience. But whereas the Aristotelians has

overestimated our store of knowledge, the sceptics had underestimated our

capacities of knowledge. Both had

ended up giving up in the search for new knowledge. The sceptics had given up because they

thought knowledge is beyond our grasp; the Aristotelians had given up because

they thought that they had already discovered everything it is possible for

us to know, and so took themselves to have nothing left to do but exposit and

comment on the works of “the Philosopher.” (Works IV 13). Bacon agreed with the

sceptics that the Aristotelians were wrong.

The Aristotelian philosophy taught in the schools and universities of

his day was bogus, and the sceptics had been right to expose its errors, along

with the errors of all the other dogmatic philosophical schools. But Bacon thought that the sceptics were

also wrong to suppose that we could not do any better. Of course the sceptics had been right when

they argued, as they famously did, that our senses are unreliable and

deceptive, and that our intellect frequently contradicts our senses — even

though it depends on the senses for all its information. But the sceptics had also been wrong, Bacon

claimed, to suppose that we therefore have no criterion for distinguishing

between the deceptive appearances produced by the senses or the intellect and

what is a true reflection of reality.

He had been able, Bacon claimed, to supply certain instruments or

“helps” (i.e., certain methods) that would assist the senses and the

intellect in gaining knowledge, just as recent technological inventions had

supplied his fellows with instruments for bettering the material conditions

of life. Bacon’s answer to the

sceptics is worth quoting at length. the information of senses I

sift and examine in many ways. For it

is certain that the senses deceive.

But then at the same time they supply the means of discovering their

own errors. Only the errors are

[obvious]; the means of discovery are to be sought. The senses fail in two

ways. Sometimes they give no

information; sometimes they give false information. For first, there are very

many things [that] escape the senses, even when best disposed and in no way

obstructed. This happens either

because of the subtlety of the whole body or the minuteness of its parts, or

because of distance, or slowness or swiftness of motion, or familiarity of

the object, or other causes. And

again, when the senses do apprehend a thing their apprehension is not to be

relied upon much. For the testimony and information of the senses has

reference always to [us], not to the universe; and it is a great error to

assert that the senses are the measure of things. To meet these difficulties,

I have sought diligently and faithfully on all sides to provide helps for the

senses — substitutes to supply their failures, standards to correct their

errors; and this I endeavour to accomplish not so much by instruments as by

experiments. For the subtlety of

experiments is far greater than that of the senses themselves, even when

assisted by exquisite instruments — such experiments, I mean, as are skillfully and artificially devised for the express

purpose of determining the point in question.

To the immediate and proper perception of the senses therefore I do not

give much weight, but I ensure that the task of the senses shall be only to

judge the experiment, and that the experiment itself shall judge the thing. [Works IV 26] The sceptics had

famously argued that sense experience is unreliable and cannot be used as a

basis for knowledge because sensory experiences are in conflict with one

another. The same object can appear

differently to different perceivers, or to different

sense organs of the same perceiver, or to the same sense organ at different

times or under different circumstances.

This is a problem because we have no independent criterion that we can

rely upon to decide which of the conflicting appearances is correct. We cannot appeal to the sense of touch in

preference to that of vision, because it is party to the dispute; or to the

experiences of “the wise” in contrast to those of fools, because we need a

way of identifying which people are wise, which we can’t provide without

begging the question of who perceives correctly (in this case, who perceives

wisdom in others). But Bacon claimed

that there is a kind of sensory experience that is reliable. It is not the experience of a particular

sense organ, or the sense experiences of a particular wise person. Neither is

it the experience of the senses when used under optimal conditions, when they

are healthy and unobstructed. It is

rather sense experience of the results of properly conducted experiments. Bacon’s idea was that

if our senses are inadequate because they give us conflicting experiences of

the same object under varying circumstances, then we can correct for these

errors by controlling the circumstances and relating our observations to

them, that is, by conducting controlled experiments. If, say, the same object looks different

from different angles or in different surroundings, then we need to keep

track of the viewing angle and the surroundings when we make our

observations; we need to actively alter the viewing angle and the

surroundings and record how the appearance of the object changes, and we need

to develop a comprehensive picture of all the different ways the object

appears under all the relevant variations in circumstances. Again, if the same object appears

differently to different people, or to the same

person at different times, then we need to identify what is different about

these people and these times. We need

to work towards a position where all the circumstances producing variety in

the appearance of the object are controlled for. Once in that position, the object will

always appear the same way. Our senses

will not deceive us when judging about the nature of the object under

controlled circumstances — circumstances that take into account all the

different things that can affect the appearance of the object. Moreover, other

investigators, replicating our experiments under the same controls, should

obtain the same results. After all,

under proper experimental conditions, the appearances to different perceivers

should not be conflicting because the circumstances that produce variations

in sensory experience would all have been taken into account. Sensory experience of the results of

properly conducted experiments should therefore always yield the same results

and so should be immune to the sceptical charge that sensory experience is

unreliable because different sensory experiences give us conflicting

testimony regarding the same object. This notion, that

knowledge should not be based simply on sensory experience, but rather on

observations that have been made under rigorously controlled circumstances

and that are replicable by others who repeat the experiment under those same

conditions, still characterizes modern science. Today, a report does not count as

“scientific” unless other researchers can replicate it in their own laboratories,

and reports that fail to meet this test are rejected. Bacon deserves the credit for being the

first to clearly articulate and promulgate this ideal for scientific

knowledge and it is one of his main contributions to the history of ideas. Hasty

induction, crucial experiments, and collaborative research institutions. One thing that getting a complete picture

of how an object varies in appearance with differences in circumstances

should do is identify different factors that affect our experience and so

correct for their influence, enabling us to identify the intrinsic,

circumstantially neutral constitution of the object. But we want to do more than that. We want to work back to the “latent constitution” of its parts, even its unobservably small parts, and use knowledge of that

constitution to predict how that object will affect and be affected by other

objects. In order to do this we need

to study what Bacon called “natural history” and we need to do experiments in

a systematic rather than a haphazard fashion.

Studying natural history involves going out and attempting to identify

all the circumstances in which the phenomenon we are interested in naturally

or commonly appears. Say we are

interested in heat. Then we will want

to go out and identify all the circumstances where heat naturally or commonly

arises (e.g., in fire, under sunlight).

But we will not stop there.

Even more important, in Bacon’s estimation, is collecting experiences

where the phenomenon occurs in surprising or unexpected circumstances (these

are the preternatural or monstrous circumstances). Swishing a piece of limestone under water

produces heat, contrary to all our expectations. A dung heap in winter steams and melts the

snow that falls on it, contrary to all expectations. These recalcitrant instances are

particularly important, in Bacon’s estimation. They provide real clues to the cause of the

phenomenon. The cause can’t just be

something that is common to all the natural circumstances where the

phenomenon occurs (there are typically many things that are common to the

different natural circumstances. It

must also be something that is common to the preternatural circumstances

where it occurs and absent from the preternatural circumstances where it does

not occur though it is expected to.

Bacon took this so seriously as to recommend taking tales of

witchcraft, spirits, and magic seriously — not because he necessarily

believed that there actually are such things, but because he thought that the

investigation of such phenomena would tell us something one way or another,

either about what exists in the world around us (supposing the tales are

true), or about what causes us to adopt false beliefs (supposing the tales

are false). In addition to doing a

“natural history” of natural and preternatural circumstances in which a

phenomenon occurs, Bacon stressed that it is important to study artificial

circumstances in which the phenomenon occurs.

“Artificial” means what is produced by art or human artifice, and as

already noted, Bacon did not think that the artificial really differs from

the natural. We must employ the same

causes to bring about an effect that nature does. That means that that the way we work to

successfully bring about change in things should mirror the way nature

works. There can be no overestimate of

the influence this last factor had on Bacon.

It is what led him to propose a theory of the latent constitution of

things. Many of the most impressive

artefacts of his day were mechanical devices: the clock, the mill, the

printing press. These devices bring

about change by communicating motion through a system of colliding

parts. Their example led Bacon to

think that nature works in the same way, and brings about all change through

motion and collision of particles too small to see Amassing a collection

of natural, preternatural, and artificial instances where the phenomenon we

want to study occurs is tantamount to applying what was later called “Mill’s method”

(from John Stuart Mill, who most famously proposed it) for identifying the

true cause of an event. Mill’s method

has us look at presences (cases where the effect occurs), absences (cases

where the effect does not occur) and concomitant variations (cases where the

effect occurs to a greater or lesser degree) and attempt to identify the

cause of the effect by considering what is present in all the cases where the

effect occurs, absent in all the cases where the effect does not occur, and

variant in all the cases where the effect is variant. Bacon already had the same idea. A “history” of natural, preternatural, and

artificial instances puts us in a position to compare these circumstances,

look for commonalities and differences, and float hypotheses about what

underlying latent constitution and latent processes are responsible for the

phenomenon. Typically, there will be

various alternative hypotheses we can formulate that will all equally well account

for the observations. What we do then

is look for or attempt to design some crucial experiment that is designed to

turn out one way if a hypothesis is correct and another way if it is

incorrect. This will put us in a

position to eliminate false hypotheses.

The notion of a crucial experiment is another of Bacon’s major

contributions to the history of ideas. As noted earlier,

Bacon was concerned to contrast this new, experimental approach to induction

with the rival inductive method of the Aristotelians, as paradigmatically

articulated in Aristotle’s Posterior

analytics. In Bacon’s estimation Aristotle’s inductions had been hasty

and based just on a study of natural phenomena, without due attention to

preternatural and artificial phenomena.

Moreover, Aristotle had gathered his observations haphazardly, as

nature happened to present them to him, rather than systematically by

formulating alternative hypotheses and then testing them

using crucial experiments. As Bacon

(rather disturbingly) put it (in some translations of his Latin), he had sat

like a student at nature’s feet, waiting for instruction, rather than adopt

the attitude of an inquisitor who uses instruments of torture (crucial

experiments) to force nature to yield up its secrets. Bacon charged that the Aristotelians had

not been careful enough in trying to discover general principles by

induction. They had, as he put it, “improperly and overhastily

abstracted from facts, vague, not sufficiently definite, faulty in short in

many ways,” (Works IV 24) so that

they could proceed to give demonstrations and “fly at once from sense and

particulars up to the most general propositions … : a short way, no doubt,

but precipitate; and one [that] will never lead to [an accurate description

of] nature, though it offers an easy and ready way to disputation” (Works IV 25). Demonstration has occupied altogether too

large a role in science up to now, as far as Bacon was concerned. It is a theatrical “idol” used to dress up

fatuous knowledge claims. It needs to

be replaced by more care in the execution of the important prior task of

induction. A significant problem

(and so a significant disincentive) to the important prior task of induction

is that it is a large one, requiring immense time and resources. To do it properly is more than could ever

possibly be managed by any single individual.

This led Bacon to propose the formation of research institutions

which, unlike the medieval universities, would be dedicated to the advancement (as opposed to mere

transmission) of learning. These institutions

would be dedicated to the execution of large, collaborative research

projects, involving extensive, programmed experimentation, carried out under

the guidance of directors, and aiming at the eventual formulation of theories

describing latent configurations and latent processes. The Royal Society of England was formed on

this Baconian model. The

doctrine of the Idols. As

Bacon saw it, a proper induction is further hampered by the fact that we have

certain intellectual weaknesses that constantly tempt us to jump to accept

grand theories even though the evidence for them is weak. (i) We like theories that are simple,

elegant, and analogous to other theories because they are easier for us to

understand and remember; and often we will accept a theory just because it

has these features. (ii) We like

theories that confirm our own personal prejudices, gleaned from education,

conversation or accidental experience, and will often accept theories merely

for that reason and in defiance of contrary evidence. (iii) We like theories that are dressed

up in fancy jargon and unintelligible technical terminology, and even though

we might not be able to make any sense of them we will repeat them as if they

were profound truths. Finally,

(iv) we like theories that are pompously displayed in the full

theatrical dress of an Aristotelian deductive system from supposedly first

principles (or some other equivalent).

All of these features are tempting to us. We have an inclination to want to assent to

theories that exhibit these features without adequately investigating the

evidence that they are based on. And

even should the evidence be against them, these same factors will make us so

enchanted with the theories that we will strive to preserve them anyway, by

making fine distinctions or trying to salvage them with ad hoc hypotheses. Bacon referred to

these four inducements to hasty generalization as “idols” of the

understanding. (He named them idols of

the tribe, idols of the cave, idols of the marketplace, and idols of the

theatre respectively.) The force of

this term is lost on us today unless we recall that Bacon was writing at the

time of the Protestant reformation and in a country that had just undergone a

reformation. In his day, a violent

reaction had set in against all the exterior forms of religious worship —

rituals, liturgies, vestments, statuary, music, incense, and so on — and a

alternative, purely inward form of worship — focusing on an intense personal

experience of God — was in vogue. By

talking about the evil influence of “idols” Bacon was presenting his point by

means of an analogy that would have been powerfully evocative for his

contemporaries. He was telling his

readers to smash the idols of the understanding as the Protestant reformers

had smashed the idols in the churches, and focus on an intense engagement

with the evidence of experience. ESSAY QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Over the

opening aphorisms of Book II of the New organon (not assigned as part of the reading for this

section) Bacon articulated what he meant by the form of a thing and took a

position on why it is that change occurs when “actives” and “passives” are

brought into contact with one another.

Obtain a copy of the complete New

organon and, proceeding from a study of the

opening aphorisms of Book II as well as of the assigned readings, attempt to

answer as many of the following questions as you can: What was the extent of Bacon’s commitment

to an atomistic or at least corpuscularian account of nature (one that

attributes all change to the mixture and separation of particles)? Is this commitment consistent with his inductivism, that is, can it plausibly be supposed to be

inductively well grounded? Is the

commitment, if there is any at all, only partial, that is, does Bacon think

that corpuscular accounts are correct only for certain phenomena but not

all? What hope did Bacon hold out for

our ever being able to reach an exact knowledge of the forms of things,

whatever their exact nature may be?

2. Kant

famously observed that while experience is able to tell us that something is

now the case, it is not able to tell us that is must always or everywhere be

so. In light of this observation, is

Bacon’s inductivist method feasible? Could any process of induction ever be

adequate to put us in a position to make a general assertion or would a leap

(i.e., a “hasty generalization” of some sort) always have to be involved if

we were to formulate any general theories of nature whatsoever? How rigorous was Bacon’s inductivism, that is, how much experiment and testing did

he think we must do before being entitled to make a generalization? Might he have thought that an inductive

leap becomes legitimate after a certain point? In answering this question, give careful

attention to the example Bacon gives of inductively discovering the cause of

heat. This example is given in Book II

of the New organon

(which you will have to obtain separately, since it is not included in the

readings for this course).

3. How

adequate is Bacon’s answer to scepticism?

Assess whether a committed sceptic might or might not be able to mount

a challenge to Bacon’s position. |