|

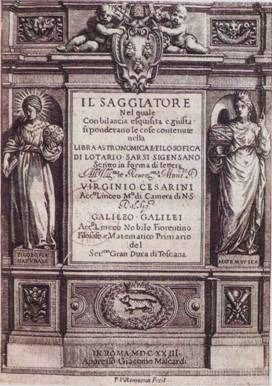

3 Galileo Il Saggiatore (The Assayer) (Matthews, 53-61)

-

Galileo “The

Assayer” The bodies that we see around us can be considered to have three kinds of qualities: spatial qualities, like shape, size, and motion; powers, like weight, solidity, and hardness; and sensible qualities, like colour, heat, and smell. Spatial qualities have to do with how a body fills space, powers with how it acts when moved, hit, compressed, or placed in the vicinity of other bodies, and sensible qualities with those features that we only learn about through the use of specific sense organs, so that those who lack those organs can form no conception of those qualities, as colours to the blind, sounds to the deaf, or tastes and smells to those who lack these senses. In describing the mechanical philosophy, Boyle had characterized it as the view that all change in nature results from just the spatial qualities of things, that is, from the communication of motion upon impact and the resulting rearrangement of shaped and moving particles in bodies. He wanted to show that the powers of bodies are not actually distinct and special properties. Since the powers have to do with how things move or resist motion, and all motion or resistance to motion is supposed to be a result of impact and the corpuscular structure of bodies, he wanted to account for their powers in those terms. He wanted at all costs to deny that the powers of bodies are further, irreducible forms or qualities inhering in specifically different kinds of material. However, powers are not the only properties of bodies. Bodies also have sensible qualities. By this I mean phenomenal or manifest qualities — qualities that you encounter directly and immediately through the use of your sense organs without the aid of any study or investigation. It takes some study and investigation to discover that a particular smell is caused by roses, and rather more to think that it may be due to particles emitted by the rose and inhaled. But even someone who has never seen a rose before experiences something when they smell a rose scent. That scent that they experience is what I am referring to when I speak of a manifest or phenomenal quality. It is what you first experience through the use of your senses without any science or study. Take another example. We might think that blue light or high sounds are caused by high frequency waves while red light and low sounds are caused by low frequency waves. But these are discoveries of recent science. For thousands of years before these discoveries were made, people who looked at roses saw something that looked immediately and obviously different to them than what they saw when they looked at violets. And likewise for hearing cellos and violins. They did not see or hear wavelengths. They saw some visible quality of red and blue in roses and violets that only sighted people can have any acquaintance with and that is inconceivable to the blind. Those manifest, phenomenal qualities are what I mean to refer to when I speak of sensible qualities. Boyle’s claim that all change in nature results just from the mechanical properties of bodies does not rule out the possibility that bodies might also have sensible qualities. But it does imply that even if bodies did have sensible qualities, those qualities would not play any causal role in nature. And that in turn means that they ought not to have any causal role to play in sensation or perception, since sensation and perception are also natural occurrences. If all change in nature is a result of the mechanical properties, then what causes our sensations of colour, heat, smell, and so on could not be qualities of colour, heat, smell, and so on existing in bodies. Instead, our sensations would have to be the result of the motion and impact of small particles on our sense organs — particles that may be nothing like the qualities they cause us to experience. But this would suggest that the sensible qualities really exist only in us, when we sense them, and that the only qualities that there are in bodies are just the spatial ones. If sensible qualities have no role to play in nature, not even in accounting for what causes us to perceive those qualities, then it is extravagant to suppose that they exist outside of us in bodies, doing nothing, as opposed to existing only in us, when they are perceived by us. (We do perceive them, so we can’t deny that they at least exist in us in whatever way it is that mental images and dreams exist in us.) This is the proposal that was made by Galileo, an earlier proponent of the mechanical philosophy. Galileo drew a distinction between what he called the “primary and real” qualities of bodies and sensible qualities. The “primary and real” qualities are the spatial ones of shape, size, position, motion, and order, and they really exist in all bodies. The sensible qualities, in contrast, are the phenomenally manifest colours, smells, and other feelings and, he suggested, they exist only in the bodies of sentient creatures. While this proposal is consistent with the mechanical philosophy it is, for all that, a surprising and even disturbing and perplexing one. When I reach towards a fire and burn myself, I think that the pain that I feel is in me for the very good reason that when I retreat from the fire I unfortunately carry the pain away with me. Something like this is the reason why, when I look at the Sun and afterwards experience a yellow visual after-image, I think that after-image is merely in me. Depending on how I move my eyes it moves with them. But the same does not hold for heat in the fire or the yellow in a grapefruit. To feel the heat I need to approach the fire and when I retreat from the fire the heat lessens, seeming to remain back where the fire is. And the same can be said for the way I experience the yellow in the grapefruit. It does not stay with me when I turn away but appears to stay in the place occupied by the grapefruit. These experiences suggest that sensible qualities exist at a distance from me, in objects. This seems particularly evident in vision, and perhaps also hearing and smell, which unlike the other senses, tell me about bodies that exist at some distance from me. Even if I can convince myself that sounds result from something hitting my ears and smells from something entering my nose, it is hard to think this about colours. Setting aside visual after-images, few things seem as obvious to ordinary sensory experience as that colours exist at some distance from us on the surfaces of bodies, not in our eyes or minds. That they should not exist outside of us at all is surprising. As well as being surprising, the claim that sensible qualities only exist in us is disturbing. It suggests that our sense organs are subjecting us to a large-scale illusion, presenting objects as having qualities they do not have. It further suggests that the world is really very different from the way it appears to us in sensory experience. If that is the case, how could we trust the senses when they tell us anything — as we need to if we are to do the sort of experimental science recommended by Bacon? Might we not be better off turning to something else, like syllogistic inference from intuitively evident first principles? How does all this fit with Bacon’s scientific methodology, which rejects demonstration, which is suspicious of all supposedly intuitively evident first principles, and which demands instead that we engage in careful induction by means of sense experience of the results of controlled experiments? We have already seen, in studying Boyle, that there is some tension between the tenets of the mechanical philosophy and those of Baconian scientific methodology. That tension becomes particularly acute with Galileo’s rejection of the reality of sensible qualities outside of the bodies of sentient creatures and the implied tenet that our senses are seriously defective. Finally, the claim that sensible qualities exist only in us can be perplexing. If sensible qualities do not exist outside us, in bodies, where do they exist? We can’t say that they don’t exist at all, since we experience them, and in experiencing them we are experiencing something and not nothing. Galileo thought that while sensible qualities do not exist in those bodies that we commonly suppose them to exist in, they do at least come to exist in the bodies of sentient creatures when their sense organs are affected by bodies. Heat may not exist in fire, but it does at least exist in the bodies of those sentient creatures that are in the proximity of the fire. But then, what is it about the bodies of sentient creatures that makes them capable of possessing such extraordinary qualities, qualities that nothing else in nature is supposed to possess? And if they do possess them, how can they possess them? How can bodies that are only supposed to have the “primary and real” qualities of shape, size, position, motion, and arrangement come to possess colour, fragrance, and heat? And supposing they can, why couldn’t insentient bodies do so as well? Confronted with these questions, contemporaries of Galileo such as Descartes speculated that sensible qualities might not exist even in the bodies of sentient creatures, but only in their minds. (This went hand in hand with the view that minds are a distinct kind of immaterial substance, which only some sentient creatures possess, so that the others are just machines that lack any feeling.) But this view is hardly any less perplexing. It does not seem plausible to claim that while roses are not red or fragrant minds are, or that while fire is not hot, minds are made hot by fire. Colours, like material or corporeal substances, have shape, size, position, motion and arrangement. How could they be qualities of minds unless the minds themselves had shape, size, position, motion and arrangement as well, and then wouldn’t they have to be material or corporeal substances, too, landing us back with Galileo’s view that the sensible qualities reside in the bodies of sentient creatures rather than their minds? Further muddles arise from the way that those who deny that sensible qualities exist in bodies ended up using words like “heat.” (Locke, we will see, was particularly confusing on this matter.) Sometimes the word was used, consistently with the theory, to refer to a feeling that exists only in us, and Galileo was generally careful to use the word, “heat,” in precisely this way, except when describing the supposedly mistaken views of others. But at other times the word, “heat” was used to name whatever it might be in bodies that causes us to have this feeling, and even Galileo lapsed into this way of speaking on occasion. For instance, he wrote, “From a common-sense point of view, to assert that that which moves a stone, piece of iron, or a stick, is what heats it, seems like an extreme vanity [i.e., something so absurd that only someone deeply conceited with their own self-importance could utter it with any hope that others would believe them]” (Matthews, 60-61). The claim is not actually “vain,” in Galileo’s eyes, because motion really is the cause of our sensation of heat. But since stones, pieces of iron, and sticks are not sentient beings and cannot be supposed to feel sensations, Galileo himself lapsed into the common way of thinking when he described them as being “heated.” On his own, considered view, to say that what moves a stone, piece of iron, or stick is what heats it really is absurd, though it is absurd for a different reason than common sense takes it to be absurd. Common sense takes heat to be something that can only be produced by something that is already hot, so that a moving body that is not itself hot could not produce heat. But Galileo took heat to be a sensation that exists only in sentient creatures so that a stone, piece of iron, or stick could not under any circumstances be said to be heated. At best, such objects could be made to move in such a way as to cause the sentient creatures that touch them to feel the sensation of heat. Confusion can be avoided by distinguishing between two different senses in which the term is used — in one way to name a feeling, in the other to name a cause of that feeling. The cause, according to people like Galileo, is nothing like the feeling. But the same name often gets used to refer to both. While we can clarify precisely what Galileo meant by “heat,” it remains a question whether he was right to say what he did about it and how he justified his claim. It also remains question how well Galileo’s position coheres with the ideals of a Baconian approach to gaining knowledge. QUESTIONS ON THE

1. What is

heat generally believed to be?

2. According

to Galileo there are some properties that it is impossible to conceive a body

not having. What are these properties?

3. What is the

basis for our belief that bodies have such properties as being red or white,

bitter or sweet?

4. How could a

body possibly have shape but no colour?

5. What

significance did Galileo attach to the fact that a body tickles more under

the nose than on the back?

6. What

determines whether our tactile sensations will be pleasant or unpleasant?

7. What is the

cause of variations in taste?

8. What

excites tastes, sounds, and odours?

9. What

accounts for the operation of fire? 10.

Is it right to say that fire is hot, i.e.,

that heat exists in fire? 11.

Why did Galileo think that a bellows increases

the heat of a fire? 12.

Did Galileo think that matter is infinitely

divisible (i.e., that you can in principle go on dividing a piece of matter

in halves forever)? NOTES ON THE

Galileo did not simply deny that heat or the other qualities he went on to discuss are in insentient bodies. Instead, he only claimed to “suspect” or “think” that this is “probably” so. This suggests that he was not capable of proving his point. Like Boyle, he contented himself with establishing the possibility of his view, and with showing that it has certain advantages that make it worth adopting as a working hypothesis or at least worth investigating further. To this end, Galileo first observed that, while “material or corporeal substances” are inconceivable apart from being supposed to have the “primary and real properties” of shape, size, position, motion, and arrangement, this is not the case for qualities like colour, smell, or taste. A perfectly transparent piece of glass or quantity of air is still a body, with shape, size, position, motion or rest, and a location relative to other bodies, though it has no colour. No body has any colour in the dark, though all continue to exist. Many bodies are odourless or tasteless, yet still exist, and so on. But shape, size, position, motion and arrangement cannot be removed from a body without removing the body itself from existence, or at least from conceivability. In Galileo’s eyes, this gives the qualities of shape, size, position, motion, and arrangement a more “primary and real” status than the qualities of colour, smell, taste, sound, or heat and cold. We have to think that bodies have the “primary and real qualities” whereas bodies do not need to have sensible qualities like colour, smell, or taste. In fact, Galileo observed, were it not for the fact that our senses show them to us, nothing would lead us to infer that bodies possess these qualities. This does not prove Galileo’s case. At best, it establishes that some qualities are more universally distributed and essential than others, not that the others do not exist. Galileo would have to agree that, simply because a body can be conceived to exist without a quality it does not follow that it might not have it anyway. Even the fact that some bodies can be found that actually lack the quality does not mean that other bodies might not still have it. However, there is a further point to Galileo’s remark that, “Were they not escorted by our physical senses, perhaps neither reason nor understanding would ever, by themselves, arrive at such notions” (Matthews, 56). In Galileo’s estimation, the “primary and real qualities” are not merely shown by our senses, but can be deduced by reasoning or understanding to belong to bodies even when they cannot be directly seen. To cite an old example, our skin has holes or pores that are too small to see. But from the presence of beads of sweat on the surface of the skin, we can infer that there must be holes in the skin through which the water inside the body passes. In Galileo’s estimation, we do not have any such independent evidence that bodies have colours, taste, or smell. The only reason we suppose bodies are hot or red is in order to explain why we feel the sensations of heat or redness when we are in their vicinity. There are no other phenomena in nature that we need to appeal to sensible qualities in order to explain. If triangles or holes exist in nature, then I could find some reason to suppose that they exist other than the fact that I sense them. For instance, I might sense something else that would have to be produced by triangular or perforated objects, such as split wood or beads of sweat on the surface of my skin. But if the only reason I can find to suppose that bodies have colours, tastes, and smells is that I sense these things — so that the only things that qualities of colour, taste, and smell do in nature is give me my sensations of colour, taste and smell — then I might as well just suppose that the colours, tastes, and smells only exist in me and are caused by some different, more generally operative qualities in bodies. Galileo proceeded to offer an illustration of what he meant to suggest. We all accept that certain tactile sensations, like those of tickles or pinches, exist only in us. This is evident from the fact that we can immediately observe that what produces these sensations is the motion of another body over certain regions of the skin. We think that the tickly feeling exists only in us, not in the body that tickles us. We think that the body only moves and that it tickles because we, not it, are ticklish (that is, susceptible to experiencing that feeling when bodies move over our skin in a certain way). This is made all the more evident by the fact that we are not equally ticklish on all parts of our bodies, even though the tickling body moves and touches them all in the same way. So it would seem that the tickle exists only in us. It is aroused in us by the motion of bodies over the more sensitive parts of our skin, not transferred to us because the body that touches us itself contains a tickle. Galileo wanted to suggest that all of the other sensible qualities are like tickles. Rather than be transferred into us from out of bodies that themselves contain those qualities, they are effects of something altogether different in bodies: their shape and motion. Over the next few pages, Galileo proceeded to sketch a theory of how this might be the case. He claimed that all our tactile sensations could be effects of bodies moving over or pressing against our skin, that smells might be produced by volatile particles rising into the nose and hitting its parts, that tastes might be produced by moist particles mixing with the saliva on the tongue, and that sounds might be produced by percussion that causes undulations in the air that are transmitted into the ears. But this is all speculation. Why should we believe any of it? Galileo tried to make the theory attractive by claiming that what holds for the case of experiencing tickles, itches, and pains ought to hold as well for the case of experiencing smells, tastes, sounds, and colours, since these are all phenomena of the same general sort. If one of them is caused by motion and impact, then, by analogy, the others ought to be as well. He tried to make this conclusion more attractive by drawing a further analogy between the way the classical element of “earth” is observed to cause tickles, itches, and pains, and the way the elements of fire, water, and air might be speculated to be responsible for causing sensations of smell, taste, and sound. Each type of sensible quality would in this way arise from the motion and impact of one of the four classical elements (earth, air, fire, and water) on a particular sense organ suited to be affected by that element. Galileo even went so far as to suggest that the really hard case, the perception of colour, might be attributed to an interaction between the fifth, celestial element, aether or light, and the sense organs. But anyone impressed with Bacon’s condemnation of idols of the tribe should not be persuaded by such attempts to support a theory by drawing analogies between it and other things. Moreover, Galileo himself was explicit that the theory is merely speculative. (He said, for example, that “perhaps” smell is produced by fiery particles.) And the bare fact that it is possible that all the sensible qualities might be produced in us in the same way that tickles are does not suffice to prove that this is in fact the case. Galileo’s theory does have an attractive feature. It explains why our noses are higher on our faces and our tongues lower down (the nose is higher to receive the fiery particles that rise up from the food, the tongue lower down to receive the watery particles that descend). Though a Baconian would call this just another idol of the tribe, if a theory that was invented for a quite different purpose is able to explain some other, previously unaccountable or arbitrary fact, that is a mark in its favour. When Galileo turned to discuss heat he tried to do more of this. He speculated that the cause of our sensations of heat is a combination of two circumstances: the presence of caloric particles, which he called “ignicoli,” that are very small and very sharp, like tiny needles or daggers, and the acceleration of these particles to a high speed. When the ignicoli are set in motion they penetrate our bodies and produce either an agreeable sensation of warmth (if there are just enough of them to open our pores and facilitate our sweating) or the disagreeable sensations of burning heat (if they start to tear our flesh apart). While this is not something that can be directly observed, it can be rationally deduced from the phenomena. We do feel pain to the extent that our bodies are being damaged. Conjecturally that damage takes the form of alterations to the physical structure of the body. By further conjecture, a stream of sharp particles, tearing at our bodies, would do this. Moreover, we do find that motion produces heat. The theory also does an excellent job of accounting for the phenomena of burning. Penetrating other bodies, the ignicoli either crumble the architecture of the body and cause it to collapse (in effect, to melt), or get caught in pores in the bodies, where they bounce and vibrate about for some time, or they tear the other bodies parts into little, fast-moving parts like themselves, generating yet more ignicoli and producing a conflagration (this is what happens when the ignicoli ignite some flammable material). An intense conflagration, that causes the ignicoli to not only tear the parts of inflammable bodies apart, but also to tear themselves apart into extremely fine and fast moving particles may even account for light, and it would be a particularly attractive feature of the theory if this were so as it would bring two sets of phenomena that were previously thought to be distinct, the phenomena of heating and burning and the phenomena of luminescence, under a single explanation. Idol of the tribe though it may be, the ability to unify disparate phenomena under a single account is an attractive feature of a theory. Galileo attempted to further justify the theory by a form of argument that we now call inference to the best explanation. He picked on a particular case that is a problem case for the Aristotelian theory and argued that his hypothesis is to be preferred because it is able to explain both everything the Aristotelian theory could explain and this problem case as well. The case is that of the heat emitted by a piece of moistened “calcified stone” (calcified stone is the lime that results from heating limestone in a cement kiln). On the Aristotelian account, this phenomenon is unaccountable since both the water and the stone can be supposed to be cold at the outset of the experiment. That the form of heat should suddenly emerge upon contact with something that is not warm, but itself cold, is contrary to anything the Aristotelian theory could easily explain. But Galileo claimed to be easily able to explain the phenomenon mechanically. When the stone, which is somewhat porous, was roasted in the kiln, ignicoli came to be trapped in its pores, where they have since been bouncing about and vibrating. Upon immersion in the water, the pores of the stone are for some reason widened, the ignicoli are able to escape, and heat or warmth is felt. (As a matter of fact, the heating Galileo described, which is actually quite significant, is the product of a chemical reaction. This indicates that the “best explanation” that can be offered for a phenomenon at any given point in history, given what then seems most plausible, is not necessarily anything close to the correct explanation, but “inference to the best explanation” has continued to be a popular means of justifying a theory down to the present day.) In the end, none of this proves that heat could not be a quality actually inhering in bodies, any more than the considerations Galileo had earlier advanced prove that colour, smell, or taste could not be such qualities. Galileo merely succeeded at articulating a theory that takes heat and the other sensible qualities to be effects of purely mechanical causes and hoped that the theory’s agreement with the phenomena, its ability to unify different phenomena under a single explanation, and its ability to account for previously unaccountable phenomena would induce people to accept it in preference to its rivals, or at least to consider it a working hypothesis that is worthy of further investigation. At the same time, however, his theory raised problems that were to continue to trouble early modern philosophers, most notably the problem of how far we can trust the senses if the theory is really correct, and the problem of where and how the rejected sensible qualities might exist. ESSAY QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Galileo

supposed that sensible qualities “reside exclusively in our sensitive

body.” Consider what this might mean

and whether this is a plausible or consistent view. Would it have been possible for him to deny

that sensible qualities exist even in us?

If they exist in us, how do they exist in us? Did Galileo mean to endorse the

Aristotelian view that for me to sense a quality like red or hot is for me to

literally become red or hot? If he is

willing to allow that sensible qualities exist in our sensitive body, then why not allow that they exist in other bodies as

well?

2. Assess the

adequacy of Galileo’s argument against the objective existence of sensible

qualities. Are the considerations

Galileo advanced for his position really compelling? Are they too compelling, that is, might

they work just as well to prove that shape and motion have no objective

existence? Might Galileo have advanced

other, more compelling arguments against the objective existence of the

sensible qualities (think of the traditional sceptical modes or the reasons

advanced by Epicurus in the letter to Herodotus)? Would these arguments have been “too

compelling” (in the sense just mentioned) had he dared to use them? Could an Aristotelian mount an equally

compelling argument for the rival view that sensible qualities do inhere in

objects? |