|

7 Descartes, Discourse on method I-II and V (AT VI 1-22

and 55-60)

–

Descartes, Discourse on method II Early modern philosophy

was profoundly influenced by developments in two other areas: natural science

and religion. These two influences did

not sit easily with one another. The early modern

period was a deeply religious era, and in France and Great Britain, the main

centers of early modern philosophy, religion took one or the other of two

forms: the external, ceremonial, and hierarchically governed religion of the

Roman Catholics, dominant in France, and the internal, enthusiastic, and

republican religion of the Reformed Church with its Puritan and Presbyterian

offshoots, dominant in England and Scotland.

These two forms of religion had been at war since the time of the

Protestant reformation. However, both

forms of religion were committed to certain fundamental Christian doctrines:

God’s role as not merely designer, but creator of the very stuff the universe

is made of, and the necessity of belief in the risen Christ for salvation and

in Christ’s status as the second person of the Trinity. Neither form of early

modern religion sat well with the mechanistic tendencies of early modern

science. The tension is nowhere as

explicit as it is in the mechanistic philosophy of Hobbes. As has been seen, Hobbes maintained that

human beings are simply machines, he denied the existence of immaterial

spirits and of the freedom of the will, and he had a conception of the Divine

nature that seemed pious only to the extent that it refrained from saying

anything about the nature God, though it seemed to hint that God has to be a

material being. As a result, Hobbes

was widely denounced as an atheist and a libertine, who suggested God is a

material thing, questioned the justice of punishing the wicked in an

afterlife (when there could be no reformative or deterrent justification for

the punishment), and held that there is no need to observe moral rules when

there is little chance of being caught and punished. Hobbes was nonetheless

able to live to a very old age without suffering persecution or more than

temporary and limited censorship of his works. There are a couple of reasons for

this. First, he was very careful not

to go too far. Second, he lived most

of his life in a Protestant country.

The enthusiastic form of the Protestant religion, which emphasized an

ecstatic personal union of the individual with God, pushed the Protestants in

the direction of rejecting ecclesiastical and civil hierarchies, viewing each

person’s religion as their own affair, and consequently instituting a broad

religious toleration and a degree of freedom of the press. This worked in Hobbes’ favour. However Hobbes was also concerned to insist

on his Christianity, and was at pains to demonstrate that nothing in his work

is actually in conflict with scripture.

He may have implied that God is material, but he never said it; in

fact he denied it, and that is what would have counted had he ever been

summoned into court on charges of heresy or atheism. And while he did maintain that our souls

are material and decay along with the body, this was not clearly

unorthodox. The Christian church had

always stressed the resurrection of the body at the final judgment, so Hobbes

could claim that it is not necessary to suppose the existence of an immortal,

spiritual soul in order to believe in an afterlife. And, as already noted, he could point out

that nothing in scripture entails that angels or devils have to be spiritual

in nature. Even Hobbes’

determinism — his denial of the freedom of the will — was not clearly

unorthodox in a Protestant country.

Calvinist Protestantism was itself deterministic and the Calvinist

Puritans and Presbyterians in While Hobbes was able

to avoid persecution and serious censorship, he did not have an entirely easy

time. His philosophy was widely

perceived as opening the door to more radical free-thinkers, who would build

on his work to deny the existence of God and an afterlife. At one point during his lifetime there was

a move in Parliament to launch a formal inquiry into the orthodoxy of his

views on religion, and shortly after his death two of his works, including Leviathan, were formally condemned and

burned at

Galileo’s Recantation

of the views of Copernicus Not surprisingly, many

champions of the new philosophy were anxious to deny any intention of offering

a “reform.” At the outset of his Discourse on method, Hobbes’ French

contemporary, René Descartes, wrote: “I could in no way approve of those

troublemaking and restless personalities who, called neither by their birth

nor by their fortune to manage public affairs, are forever coming up with an

idea for some new reform in this matter.

And if I thought there were in this writing the slightest thing by

means of which one might suspect me of such folly, I would be very sorry to

permit its publication.” His protestations to

the contrary notwithstanding, Descartes did mean to propose a reform in

natural philosophy. But, though this

is what he meant to do, he was reluctant admit it. It is not just that he was afraid, though

he had good reason to be. As many of

his comments in correspondence with his friends make clear, he also believed

that flying in the face of people’s prejudices is no way to make

progress. It simply incites them to

reject and suppress your work, and you end up achieving nothing. It is much wiser, Descartes thought, to

proceed in a more devious fashion: Try

to convince the authorities that the principles you are advocating do not

touch on established beliefs — or that if they do they serve to support them

by setting them forth in the light of a new method of presentation. Then, once you have convinced them to

accept your apparently innocent first principles, you can leave it to them to

draw the conclusions that necessarily follow from these principles. Here, for example, is what Descartes wrote

to Mersenne on the eve of the publication of his Meditations on first philosophy: and I can tell you that these

six Meditations contain all the fundamentals of my physics. But this should not be broadcast, please,

because those who favour Aristotle might then have difficulty in approving of

them, whereas I hope all who read them will become insensibly accustomed to

my principles and recognize the truth of them before they discover that they

destroy the principles of Aristotle.

Sir, I have had here all

afternoon a distinguished visitor, M. Alphonse, who discussed the Descartes had only

been impelled to write what he did because, he claimed, of a sceptical

crisis. In the early years of the

Protestant reformation, Catholics had attacked the Protestant rejection of an

ecclesiastical hierarchy by resurrecting sceptical arguments that showed the

inadequacy of all our knowing powers and the consequent inability of any

individual to discern the Word of God simply from a personal engagement with

scripture, unassisted by traditional and divinely sanctioned authority. However, the sceptical arguments were so

powerful that they proved a double-edged sword, allowing Protestants to

retort that the sceptical arguments applied as well to Bishops and Popes as

people, and that no one unassisted by a direct infusion of Grace and born

again in the Word could overcome the natural weakness of the human knowing

powers. In the end, the only winners

had been atheists and libertines, who wanted to cast all belief and all

religion into doubt. Descartes

presented himself as someone who had found a way to reply to the sceptics. However, the challenge

facing mechanical philosophers in Catholic countries was not just how to

replace Aristotelianism without looking like reformers, but how to justify

replacing it with an alternative as apparently irreligious as the mechanical

philosophy. The Churchmen in Because the church in

Catholic countries was still too powerful, and too authoritarian to be

effectively resisted, those who wanted to advocate mechanistic natural

philosophy had only one choice: to seek for some form of accommodation — to

do for Democritus and Epicurus what Thomas Aquinas had done for Aristotle:

reinterpret their philosophy in such a way as to make it acceptable to

Christians. Descartes was the prime

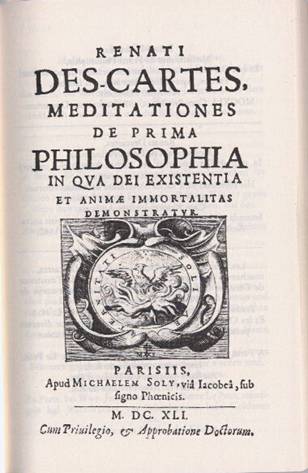

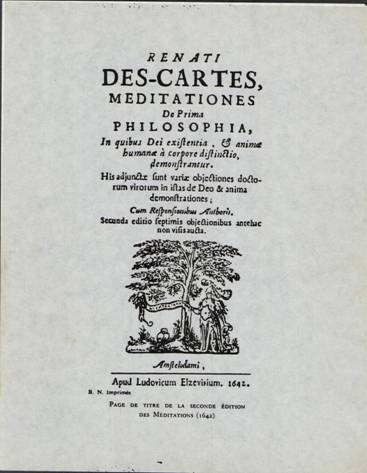

architect of this accommodation. The

sub-title of the second edition of his most famous work, the Meditations, “in which the existence

of God and the distinction of the human soul from the body is demonstrated,”

clearly indicates the direction Descartes wanted his project to take. He was out to write a

Title

pages of the first and second Latin editions of Descartes Meditations. The

subtitles changed between the two editions.

Whereas in the first Descartes claimed to demonstrate the existence of

God and the immortality of the soul, in the second he instead claimed to

demonstrate the existence of God and the distinction of the soul from the

body. The revised claim is the correct

one. philosophy that would

establish the foundations for a mechanistic science of nature and his Meditations were directed to lay the

groundwork for such a science by showing: •

that all that really exists in the physical

world are extended particles in motion, •

that there are no real qualities of hardness,

ductility, and the like inhering in bodies and distinguishing matter into

different kinds or elements, •

that sensible qualities are merely feelings in

us, and •

that the proper

way to gain knowledge is not by a method of observation and experiment

relying upon the senses but by the use of pure reasoning. But you would not learn any of this from reading the title

page of the Meditations. It is instead advertised as an attempt to

prove the existence of God and the distinction of the soul from the body. In billing his work in

this way, Descartes was not simply being devious. In the Meditations

he offered repeated demonstrations of the existence of God, and while he

never actually got so far as to prove the immortality of the soul, he did try

to establish that human beings have spiritual souls, and are not just

bodies. Christian believers of all

types were confronting a sceptical crisis, due not so much to attacks by

atheists but to their own mutually destructive employment of sceptical

arguments against one another. New

arguments to support the old beliefs were needed. Descartes doubtless hoped to profit by this

situation and insinuate the mechanistic philosophy at the same time as he

performed the service of setting religious belief beyond sceptical attack. Neither should we

think that Descartes’s attempts to prove the

existence of God and the distinction of the soul from the body were purely

opportunistic. As he made clear in Discourse V, there are excellent

reasons for taking human nature to be non-mechanical in its operations: the

human reasoning power is, as he put it there, a “universal instrument,” that

is, it is versatile and able to figure out how to deal with novel

difficulties. It can learn from its

mistakes and it can discover universal principles from which it can calculate

in advance how best to approach problems.

A machine, in contrast, particularly a machine of the type Descartes

and other early modern philosophers were familiar with (a mechanical device)

can only do the particular task it was designed to do. Adapting it to perform

multiple tasks requires introducing new design elements, a new element for

each task, and the machine rapidly becomes too complex and unwieldy. Moreover, it is only through introducing new

design elements ahead of time that the machine can be made to perform

different tasks. It remains able to do

only what it was previously designed to do and lacks the ability to figure

out how to deal with novel situations. The non-mechanical

components of human reasoning are particularly evident in speech, where we

seem to be confronted with an infinite number of tasks — answering questions,

describing experiences, giving instructions, recalling events, and on and

on. Descartes believed that it is simply

impossible for any machine to be adequately designed to perform these tasks,

so that the use of language serves as a powerful indication of the ability to

respond spontaneously to unanticipated and novel circumstances, an ability

that, Descartes supposed, cannot be explained mechanically. (It is no objection, therefore, that

machines might be designed to make noises resembling human speech. Such machines would have to be designed to

make certain noises in response to certain stimuli, and while they might

momentarily trick us into thinking they are rational we would soon learn that

they always respond in the same way to the same sort of stimulus, and that

would show to us that they are not reasoning but merely responding.) However, Descartes

seems to have thought that the use of speech serves as more than just a

particularly effective demonstration of our possession of a non-mechanical

reasoning ability. He supposed that

our use of speech shows, in addition, an ability to grasp the sense or

meaning of what has been said to us, and provides us with a way to

communicate the sense or meanings that we have grasped to others. We are able to “respond to the sense” of

what is said, as he put it. This is

something that exceeds the power of any mechanical device. All that a mechanical device can do is

move. If it is hit or its parts are

hit, those parts can move in ways that, say, compress a bellows and cause a

sound to be emitted, or turn the drum of a player-piano and cause a musical

score to be played. But we do not

think that in addition to performing these motions the machine does something

else that we would call grasping the meaning or the significance of what has

happened. If the bellows is compressed

and the sound is emitted we do not think that this is because the machine has

felt pain or understood that someone is saying something false and is wanting

to object to the error. We simply

think that it is moving in a certain way in response to stimuli. But we ourselves are aware of more than

that. We do not just feel our sense

organs, nerves, and brain moving in different ways. We feel pain or pleasure, see colours, and

grasp the meaning of signs. When we

use language we use it to communicate these thoughts, feelings, and

intentions to others. And when we hear

others using language, it is hard for us to think that it is merely a

programmed response made by a machine.

We rather think that it is indicative that they are experiencing

sensations and thoughts and meanings in the way that we do, and that they are

communicating these experiences to us. In previous lectures,

I noted that the lived qualities of our experience, our feelings and

sensations, pose a serious problem for a mechanist like Hobbes, who thinks

that nothing exists inside of us except motions of particles. We know from our personal, lived experience

that there is more to the world than that.

Colours, tastes, and pains also exist.

But where do they exist, and how?

If the external world consists just of shaped particles in motion, and

we ourselves are no more than that, then there is no obvious answer to this

question because it is unclear how any arrangement or motion of shaped

particles could constitute a colour, taste or pain. Unlike Hobbes, Descartes had an answer for

this question. Like Hobbes, he

supposed that we human beings have bodies that operate in purely mechanical

ways. But unlike Hobbes, he supposed

that there is something more to us. In

addition to bodies we also possess minds.

Motions and arrangements of shaped particles in our bodies cause our

minds to feel certain things and to experience certain sensations, feelings

that are unlike any motion or arrangement of shaped particles and sensations

that have qualities that are not reducible to shape and motion. For Descartes the

supposition that we human beings have minds was therefore not just a counsel

of policy. It was an inescapable

conclusion from the evidence that human nature and particularly the human

reasoning and speaking abilities are intractable mechanically. And it was the

product of an inference to the best explanation for the felt qualities of

experience. Something has to be

responsible for these things, and, if it is not a machine, then it might well

be a immortal soul or spirit. And if he could tag on the claim that the

soul or spirit is “immortal” all the better. (Descartes did this on the title page of

the first edition of his Meditations,

though when it was pointed out that he had actually failed to anywhere

demonstrate that the soul is immortal, he modified the title to claim, more

modestly, just that he had established that we must have souls that are

radically unlike our bodies.) Descartes saw this as

the key to reconciling religion and mechanistic natural philosophy. We could split the world into two parts: a

realm of immaterial minds or souls, angels, and God, and a realm of extended

particles in motion. Religion could

describe the former world, where the rules of ethics and commands of God are

the only laws, and natural philosophy could describe the natural world, where

the laws of motion and collision are operative. The two worlds could peaceably coexist,

each running in their own separate ways, but they would also meet within the

human being, who is a unique and special union of the two distinct

substances: extended, moving matter and thinking, sensing, willing mind, the

mind receiving its sensations as a result of “observing” motions set up in

the brain as a consequence of the body’s being hit by flying particles, and

the body in turn being moved not only by impacts from without, but by

commands of the mind within. Christian theology had

an impact on the development of Descartes’s

philosophy at this point. If it is the

soul that senses and feels and grasps the significance of signs, and, as a

matter of Christian doctrine, only human beings have souls, then it follows

that non-human animals must not really be sentient or intelligent, even at a

rudimentary level. They must simply be

machines. This seems

counter-intuitive, but Descartes bit the bullet on the matter and maintained,

with the Christians, that the ancient tradition ascribing souls of varying

capacities to all living things, even plants, is mistaken. Descartes insisted that it is evident that

animals have no speaking or reasoning ability whatsoever, but merely

instincts implanted in them by nature (that is, by the way the machine of the

animal body was designed). Thus,

animal cries and even the speech of parrots are just noises that the animal

body makes in response to set stimuli, and any abilities animals may have to

solve problems better than we do are indicative of a lack, rather than a

presence of reasoning ability. This is

because reason is a universal instrument, which entails that the more you

have of it, the better you ought to be able to perform at all tasks

whatsoever. If animals only perform

some tasks better than we do, but not all, that is an indication that they

are not exceeding us because of superior reasoning ability, which would have

to imply a general superiority, were it to exist. They must rather be acting simply out of

instinct, which is nothing more that a feature of the mechanical design of

the animal body. QUESTIONS ON THE

1. From what

does the diversity of our opinions arise?

2. What are

the sciences of mathematics and philosophy good for?

3. What was

the chief cause of Descartes’s delight with

mathematics and his dismay with philosophy?

4. After

abandoning the study of letters, what two sources did Descartes turn to in

the search for knowledge?

5. What led

him to subsequently reject one of these two sources as well?

6. What excuse

did he offer for proposing an innovation in scientific method, despite the

danger that it might be perceived as reformist?

7. What are

the disciplines that Descartes thought most likely to be able to contribute

to his plan?

8. In what way

does geometry serve as a model for all the things that can fall within human

knowledge?

9. Why was it

so important to Descartes that he begin his investigations with absolutely

certain and indubitable truths? (This

is the first of his four rules of method). 10.

Could we distinguish between machines that

have been perfectly made to look and behave like animals and real animals? 11.

What are the means by which we can distinguish

between machines that look like human beings and real human beings? NOTES ON THE

Descartes prefaced his

three essays with a little essay on method, the Discourse on method. Discourse

I opens with a joke about the distribution of good

sense, which must of all things be the most equitably distributed because no

one can be found who would confess that they did not get their fair

share. But the joke leads to a couple

of serious points. Descartes meant to

suggest that we probably really are all endowed with an equal measure of good

sense. Therefore, there is no one who

has the right to set themselves up as a superior authority to everyone else

in this matter, and dictate what others should think. Moreover, if people do appear to be stupid,

it is not because they are lacking in good sense, but because they are

lacking in something else: method — the ability to apply their good sense in

the right way. Descartes claimed to

have come up with the right method for gaining knowledge, and in the Discourse he described it. By his own confession

over the autobiographical remarks he made in Discourse I and II, Descartes had quickly become disgusted with

the education he had received. He had,

however, retained a degree of respect for three disciplines: logic, geometry,

and algebra. While Descartes thought that there are problems with each of these

disciplines considered individually (logic does not help us discover new

things, geometry exhausts the imagination, algebra

exhausts the intellect), he also thought that there must be something

fundamentally correct about all of them, since they are so successful. What is more, if we keep in mind the point

of the opening joke (that what makes one person, and by implication one

science, smarter than another is not more good sense, but a better method),

then this success in logic, geometry and algebra probably has something to do

with their method. Thinking about this,

Descartes noticed that the same method is employed in all three

sciences. Logic, geometry, and algebra

are all deductive sciences. They

proceed by deriving more difficult or complex propositions from certain

initial definitions, axioms, and postulates assumed at the outset. Realizing this, Descartes proposed to make

some “essays” (trials or attempts) at applying this method within the context

of other disciplines — to the science of optics in the Dioptrics and the science of

meteorology in the Meteorology. He also attempted to apply a refined

version of the method to geometry itself in the essay on geometry. When he did so, he discovered that he was

able to make significant discoveries. This was all the evidence he needed to

convince himself that he had stumbled on the correct method for obtaining

knowledge. Descartes described

his method as involving the application of the four rules laid out towards

the end of Discourse II (AT VI 18-19). The rules recommend that we (i) start

from clear and evident first principles, (ii) determine what we can know

about the most simple things first and only then move to more complex things,

(iii) arrive at our knowledge of the more complex things by deduction

from what we know about the simples, using the axioms identified at step (i),

and (iv) make frequent reviews of our work in order to correct any

mistakes that might creep in. These rules reflect

the way work is carried out in the fields of logic, geometry, and

algebra. In all of these fields,

certain rules are assumed at the outset, and a certain universe of discourse

or set of simple elements for those rules to work upon is formally specified. In Euclidean geometry, for instance, the

rules are the rules for ruler and compass construction of geometrical

diagrams, and the elements are points, lines, planes, solids. In sentence logic the rules are an

inference rule and certain axiomatic sentences and the elements are the

sentence letters and the connectives like “and,” “or,” and “not.” Once the elements and the rules have been

specified, we go on to perform constructions or give proofs and so generate

more complex figures (in geometry) or sentences (in logic). When we do this we make frequent reviews of

the constructions and proofs to ensure that we have not made any mistakes in

the application of the rules. The same

can be said for demonstrations in algebra. The main difference

between Descartes’s method and the method of

geometry, logic, and algebra is that in geometry, logic and algebra the rules

and the simple elements that they are applied to are sometimes simply

arbitrarily stipulated or assumed to exist or to be true,

and this is not something Descartes was willing to countenance. We cannot simply assume our first

principles, even provisionally, but must know for certain that they are

true. And the simple elements cannot

be just any arbitrarily concocted things, but must be the simple elements we

commonly encounter in our thinking. For Descartes, it was

particularly important that the first principles be certainly and evidently

true, and not merely assumed. Were there any uncertainty in the first

principles, everything we derive from them would be open to question. There had been too much arbitrary system

building in the past, Descartes observed, and all that it had produced was

conflict, disputation, and uncertainty over which of many different,

arbitrarily constructed systems is the correct one. The only way to make progress is to not

even begin unless we have first assured ourselves that our fundamental

principles are impeccable. Interestingly, the

rules of Descartes’s method do not just reflect the

way researchers proceed in logic, geometry, and

algebra. They also reflect the way a

mechanic proceeds on the shop floor. A

clock maker sitting at a table in front of a pile of gears and springs and

rods is looking at a collection of simple elements that, when carefully

assembled in accord with certain rules, will build a more complex

device. Descartes’s

method is designed so that, when applied to such fields as physics and

cosmology, it will induce us to treat the parts of the natural world as so

many simple components for a mechanical device. It has a built-in tendency to suggest a

mechanical view of nature. There are two,

further, especially striking features of Descartes’s

method: the order of rules (i) and (ii), and the source to which we appeal

for our information at step (ii). Note

that when we follow the method, the first thing we are supposed to do is

discover absolutely certain first principles (what presents itself so clearly

and distinctly to the mind that there is no room to doubt it, as Descartes

put it). It is only after we have done

this that Descartes envisioned examining our ideas and breaking them down

into their simplest component parts.

This is a reversal from Hobbes’ method, where we are first supposed to

consult sensory experience in order to discover simple elements that we put

together in definitions of terms, and only then relate terms to one another

to formulate the first principles of a science. Indeed, it is more than just a reversal,

because whereas Hobbes saw us obtaining our knowledge of simple natures from sensory

experience, Descartes looked to a quite different source. This is not a point that is immediately

evident from his statement of the four methodological rules, but it is quite

clearly indicated by some remarks he made earlier on in the Discourse. In Discourse I, after recounting how he

came to be disgusted with the learning he had received while at university,

Descartes remarked that he had resolved “to search for no knowledge other

than what could be found within myself, or else in

the great book of the world.” But

towards the close of that section he confessed to feeling the same disgust

with common sense and worldly knowledge that he had formerly felt for

academic teachings. He had discovered,

upon investigation, that “there was about as much diversity [in the customs

of other people] as I had previously found in the opinions of the

philosophers” so that “as long as I merely considered the customs of other

men, I found hardly anything there about which to be confident.” This left

only one alternative. Disgusted both

with academic teachings and with common sense, he “resolved one day to study

within myself.” It is this source,

meditation upon the ideas that he found within himself that Descartes meant

to turn to at the second step of his method.

He was looking for a kind of pure intellectual knowledge, divorced as

much from everyday experience as from scholarly authority. Descartes’s proposed

method is even more fundamentally opposed to Aristotle’s and Bacon’s methods

than it is to Hobbes’. For Aristotle,

experience does not simply supply us with the raw materials for definitions,

but with the basis to go on to discover general rules by induction. For Bacon, likewise, we must proceed

inductively from experience and formulate grand theories and fundamental

principles only after careful testing.

In contrast to these methods, which go up to generalities from sense

experience, Descartes’s method is “top-down.” We formulate our fundamental principles

first, and only then apply them to experience. Thus, in the hands of Descartes, the

tension that has already been observed between the a

prioristic tendencies of the mechanical philosophy

and the inductivist and empiricist ideals of Baconian science turns into a divorce. Mechanical philosophy abandons experience

and relies exclusively on reasoning from introspectively self-evident first

principles. This raises two

questions: If we are not going to

consult experience, where do we get our first principles and our ideas of

simple natures? And how can we be sure

that they are correct? The job of Descartes’s Meditations

on first philosophy and Principles of Philosophy is to answer

these questions. ESSAY QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Assess the

strength of Descartes’s arguments for the existence

of a soul distinct from the body, as those arguments are laid out in Discourse V.

2. Assess the

strength of Descartes’s reasons for denying that

animals have souls.

3. Speculate

on how Hobbes would reply to Descartes’s reasons

for claiming that rational souls “can in no way be derived from the

potentiality of matter,” drawing on his account of the causes of the use of

signs and the basis for our reasoning as that account is laid out in Human nature IV-VI; De corpore

I.1-5, VI.1-6,11-18; and Leviathan IV-V.

4. Consider

which (if either) of the two, Hobbes or Descartes, had the best arguments for

his position on human nature. Was

Hobbes’ attempt to come up with a mechanical account of the workings of the

mind any more compelling than Descartes’s reasons

for claiming that there can be no such account? |