|

15 Descartes, Meditations VIb (AT VII 80-90)

Over the second half of Meditations VI, Descartes looked in more detail at what he could

know about material things. His

investigation was guided by the principle that “because of the very fact that

God is not a deceiver … it is impossible for there to be any falsity in my opinions

which I cannot correct with another faculty God has given me” (AT VII

80). He was particularly concerned

with the opinion that material things resemble the ideas we receive of them

through our senses, right down to their weight, heat, colour, and taste, and

with a related opinion that spaces in which there is nothing that can be

sensed are empty. Together these

opinions entail that space is distinct from body, because there can be spaces

where there is no body, and because bodies have other qualities than just

those that have to do with being spatially extended. Descartes wanted, on the contrary, to

identify space and body with one another, and hold that wherever there is

space there is body and that body is nothing more than cut-up bits of space. To support his position, he offered an account

of God’s purpose in giving us sensations, an account that takes off from an

understanding of our nature as thinking beings, who

have been joined to a particular body in such a way that their continued

union can be facilitated or impaired by surrounding bodies. (Descartes liked to speak of things that

facilitate or impair the mind body union rather than things that might

preserve us or kill us because he considered the mind to be immortal.) This investigation culminated in the

statement that “sense perceptions are, strictly speaking, given to me by

nature merely to indicate to my mind which things are agreeable or

disagreeable to that combination of which it is a part,” and not for

recognizing “the essence of bodies placed outside of me.” (AT VII 83) This conclusion gave rise to a further

problem arising from the fact that there are cases in which our sensations cause

us to impair or even destroy the mind body union. (The disease of dropsy, which is

characterized by feelings of thirst that worsen the condition if satisfied,

is an example.) Descartes attempted to

resolve this problem over the closing pages of the mediation. This set of notes culminates with a discussion

of two problems raised by the position Descartes took in Meditations VI: the problem of mind/body interaction, and a

problem his identification of body with space posed for accepted Catholic

doctrine on the sacrament of the Eucharist. QUESTIONS

ON THE

1. Why is it that even

though Descartes thought he could demonstrate that corporeal things must

exist, he still did not think that those things exist exactly as we grasp

them by sense? What must be true of

them?

2. What things did

Descartes think are taught to us by nature and what by a habit of making

reckless judgments?

3. What is the proper

purpose for which sensations were given to the mind?

4. Did Descartes think

that all the motions of our bodies are mechanically caused?

5. What is necessary if

the mind is to be affected by the body?

6. Does the brain feel

pain?

7. Why is it in fact

better that our senses should occasionally deceive us about what is good or

bad for us?

8. What needs to be done

in order to be sure that our senses are not deceiving us?

9. In what does the

difference between dreaming and waking experience consist? NOTES

ON THE The proof of the existence of material things

given over the first half of Meditations

VI establishes that my sensory ideas must be caused by something that is

spatially extended. This is because spatial

extension is the one feature that is objectively present in my sensory ideas

that I know to be a real, positive thing rather than a materially false idea

of nothing. And God would be a

deceiver if the cause of my sensory ideas did not actually contain everything

that is objectively present in those ideas. But while Descartes’s

proof establishes that my sensory ideas must be caused by a spatially

extended thing or things, it does not justify my earlier opinion that the

causes of my sensory ideas must be spatially extended in exactly the way the

objects depicted in those ideas are spatially extended. Because God is not a deceiver, there can be

no incorrigible falsity in my opinions.

But in this case, subsequent sensory experience and reasoning tell me

that objects are not always extended in exactly the way they are depicted as

being extended in my initial sensory experiences. Square towers seen from a distance look

round, and many distant objects appear to be much smaller than they actually

are. There are many other such

examples. This having been said, Descartes was unwilling

to retreat to the view that all we can ever know for sure is just that our

bodies are extended in some way or other.

Careful use of our senses and our reasoning ability to correct one another’s

information and one another’s speculations ought to bring us some way towards

the truth, and there are certain strong natural impulses we have on these

matters that cannot be denied. For Descartes’s

larger purposes (notably, establishing that we can know that body is nothing

more than just spatial extension and is not heavy or solid or hot or coloured, etc.), I can be assured of

at least these general things: that there are many different bodies in

existence, that one of these bodies is special to me, and that the various

other bodies can affect this one special body, some for better, others for worse. Though, as a thinking being, I am “really

distinct” from anything extended, it appears to have been the will of God

that I be unified or bound up with a particular extended thing, my body. As a thinking thing I am also likely

“naturally immortal,” simply because I am not extended in space and so cannot

be broken to pieces. But this natural

immortality notwithstanding, God appears to have willed that I do everything

in my power to preserve my union with the special body I call my own. To this end, God has not joined me to my body

in the way a sailor is joined to a ship.

A good sailor understands the state a ship is in, and knows when it has

fallen into disrepair and what must be done to sail it out of danger. But I do not understand these things about

my body. Instead, I feel them. When the body is in disrepair, I feel pain

and a need to move it in ways that will remove the pain even though I may not

understand why those motions are effective.

Likewise, when the body is in danger or in need of things like food or

drink I feel sensations like fear, hunger, or thirst that drive me to do what

is needed to keep the body in the state required to “preserve the mind/body

union,” that is, to prevent what we call “death,” which is really just the

separation of the mind from the body.

I don’t understand the mechanism of the body or how other objects

interact with it to benefit it or harm it.

I don’t know what makes different foods nutritious or noxious. I just feel needs that prompt me to eat or

drink, and I experience smells and tastes and feelings of heat and cold that

prompt me to eat or drink this rather than that, or do other things that are in

fact necessary for my health, that is, my continued union with my body. Though these feelings do not give me the

sort of understanding of the way my body interacts with its surroundings that

a sailor has of the way a ship works, they are particularly effective means

to induce me to do what is in fact necessary to preserve the mind/body

union. The sailor’s understanding

takes time to acquire and even when acquired it may not motivate the sailor

with any strong concern, as the sailor can simply decide to sail the ship to

pieces and then transfer to another.

But I needed to be motivated to act in the right way to preserve the

mind/body union while still a child who lacked the reasoning ability, or a

young adult, who had it, but lacked the instruction. And I could not be allowed to let the body

fall into disrepair the way a sailor can, who sees the state of disrepair the

ship is in but does not feel any pain over that fact. Thinking along these lines led Descartes to

conclude that the reason all of my sensations were given to me was to assist

me in preserving the mind-body union.

Hunger, thirst, and other appetites teach me what is necessary for me

to do to maintain the body. Pleasure

and pain teach me what objects to pursue and avoid. Smells and tastes teach me what objects are

nutritious or noxious. Colour and

sound to enable me to tell bodies apart from one another when observed from a

safe distance. And so on. The purpose of these sensations is not to

reveal the essence or the properties or the internal constitution of objects

to me, but simply to assist me in determining which are beneficial and which

harmful to the mind body union. Having drawn this conclusion, Descartes was in

a position to reject the natural impulse to consider bodies to be coloured or

hot or cold or possessed of other sensible qualities like those we find in

our sensory ideas. This impulse is a “juvenile

preconception,” formed in our youth and never subsequently considered. When we consider what God’s purpose was in

giving us sensations, we realize that it was never to reveal the nature of

external objects to us. The proper

tool for investigating that nature is just the understanding, and it tells us

that we can only be assured that bodies are extended. Our impulse to think they are more than cut

up bits of space was given to us for an entirely different purpose. The prejudice that spaces that do not contain

anything that affects our senses must be empty must likewise be

abandoned. All we can justly conclude

is that such spaces do not contain anything that it is important for us to know

about for purposes of survival. What

we have since learned about germs and disease, or environmental toxins and

radioactivity shows that Descartes was mistaken about this, but it was a

plausible enough thing to think for the time.

It is, moreover, entirely consistent with the view that these spaces

are not truly empty but contain things too small to see. That these things should happen to be

dangerous to the mind/body union is something Descartes himself noted when he

mentioned poisoned food (poisoning was a favourite method of assassination at

the time). God cannot be expected to

have made us sensitive to everything in

the environment that might be dangerous to the mind/body union, he

observed. He is not obliged to make us

omniscient. It is enough that we

understand that his purposes in giving us those sensations we have was to

enable us to do something to

preserve that union, rather than to give us insight into the true nature of

things. Sensory

illusion. There is a more serious problem with this

account of the purpose of sensory experience.

It is one thing for our senses to fail to inform us about things that

are dangerous to the mind/body union.

It is quite another for them to misinform us, and induce us to do

things that might be bad for us. Some

of this might be due to willful perversity on our part, as when we persist in

consuming in alcohol or tobacco or other substances that appear noxious to us

on first encounter, or when we spice and season foods to make them

artificially palatable so that we over-indulge. But there are other cases where we cannot

so easily be blamed. Descartes

instanced the sensation of thirst felt by a person with dropsy — a sensation

that, if satisfied, would actually worsen the body’s condition. Should we treat these sorts of experiences

the way we treat experiences of square towers that look round from a distance

— as evidence that what our senses tell us about what is good or bad for the

mind/body union is not implicitly to be trusted? This is hardly tenable. There is a particular urgency to our

obtaining knowledge of the state of our own bodies. We cannot afford to indulge in doubts

about, say, whether we really need to move away from the fire or not. But

given the particular urgency of this matter, it is particularly disturbing

that God should not have given us reliable sensations of pleasure and

pain. How is this fact to be

reconciled with his goodness? Descartes’s reply to this problem

what that this is a case where God really could not have made things any

better than he did. This sort of

design flaw is one that is inevitable when making a being that is a union of

a mind with a body. To explain why, Descartes

developed a theory of the physiology of sensation, and an account of the

mechanics of the mind/body union. The body, Descartes observed, is an extended

thing, and as such is divisible into a number of parts, indeed into

infinitely many parts. But the mind is not divisible into parts. It might carry out different activities,

such as willing or understanding or sensing, but it is not divisible into a

willing part that is set outside of the understanding part, or a sensing part

that is set outside of the other two (the sensing function might be a

redundant one that the mind need not perform, but it is not an external part

that could be cut off with a scalpel).

Moreover, experiments with amputations would seem to indicate that the

mind is not in communication with each and every one of the body’s parts (I

find myself to be as completely and wholly contained in what is left of my

body after the loss of a limb or an eye as I was previously in the whole;

none of my mind seems to have been cut off with the amputated part). Insofar as it is united with the body, it

is joined to it just at a small part, likely in the brain. If we accept that the mind communicates with

the body in the brain, and that external objects communicate with it at the

surface of the sense organs, something has to happen to bring the effect from

the sense organ to the mind.

Consistent with his belief that all we can be sure bodies have is extension

and motion, Descartes supposed that what happens in sensation is that certain

bodies either emit or reflect particles or themselves fly through the air and

hit our sense organs. Depending on the

shape and motion and size of these impacting bodies, the sense organs are

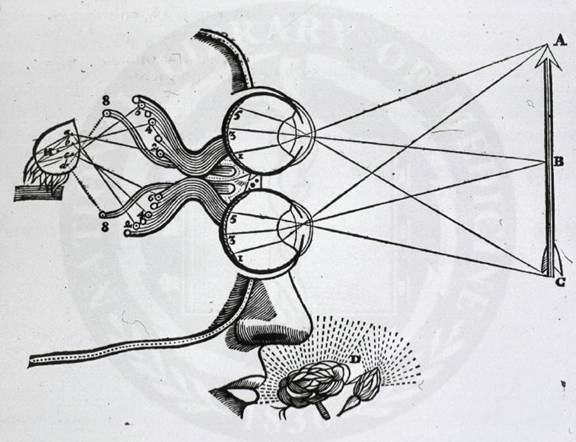

impressed, like wax, or made to vibrate, like drum skins. Behind the sense organ Descartes supposed

there to be a number of “tubes” or “strings” — the nerves. (If the nerves are tubes, then they are

filled with a very fine, vaporous fluid or gas called the animal spirits.) The effect of impression or vibration of the

sense organ is to “pull” on the nerve cord, or change the motions of the

animal spirits flowing through the nerves.

These effects are propagated along the nerves and into the brain,

where a physical organ called the corporeal imagination is impressed. Impressions on the corporeal imagination in

turn, through more nerves, propagate impressions to the part of the brain

that communicates Even if this story is not correct in all of

its details, it makes a general point that Descartes took to be beyond doubt:

given that our bodies are extended and our minds capable of communicating with

them only at a point, it is inevitable that sensation be the product of

transmitting a signal from receptors on the body’s surface in to the locus of

its communication with the mind. But

this means that, equally inevitably, there will be some chance that the

process of sensation will be interfered with, due to agents acting within the

body to interrupt, alter, or even generate a signal in the absence of its

usual cause. This is a feature of the

design that follows necessarily from the fact that an unextended mind has

been joined to an extended body, and even God could not do anything to

rectify it. In the case of vision and hearing this problem

is magnified, because these senses inform us of things that exist at a

distance from us, and there is a further chain of causes (e.g., reflected and

refracted light rays, echoes) intervening between the object and the sense

organ, creating yet more avenues for interference or distortion. God has designed us in such a way that certain

kinds of signal, coming to the locus of the soul from the receptors on the

outer surface of the body, arouse certain kinds of ideas of sensation in the

mind. And, being all good, God will

have made us so that the ideas that are aroused by a signal are the ones

that, in the great preponderance of cases, we ought to get: the ones that

will correctly represent whether the object is good or bad for us and that

will correctly inform us about where those objects are and how they are

shaped and moving. That is: • the ideas we get of the shape, size,

position, order, and motion of objects are ideas that represent the actual

shape, size, position, order, and motion of the objects normally causing the

signal; • the ideas we get of the sensible

qualities contained within a particular figure at least correspond to some

smaller structure of parts within the figure of the objects normally causing

the signal so that same corpuscular structures always bring about same ideas • our ideas of pleasure and pain are

caused by truly beneficial or harmful corpuscular structures in the objects

normally causing the signal; • our sensations of bodily states like

hunger, thirst, fatigue, and cramping, are linked to volitions to move our

bodies in ways that are truly beneficial to the union. It is just that, sometimes, these signals can

be interfered with, either by very small, undetectable parts entering into

the bodies that normally cause a sensation, or by some agent interfering with

the transmission of the signal en route. God can do nothing to prevent this, and it

is rather a mark of his goodness that we have been designed so as to get the

correct ideas in normal circumstances. This means that, in normal circumstances, we

can trust our senses to inform us accurately about the disposition of objects

in space around our bodies, about at least their larger-scale shapes, sizes,

positions, orders and motions, about which ones are different in ways that do

not depend on their gross size or shape, and about whether they are good or

bad for us. Moreover, when mistakes

are made they will typically be the result of some specific agent interfering

with the connection between one of the sense organs and the brain. It is unlikely that all five senses,

distributed throughout the body as they are, would simultaneously be attacked

at once. Consequently, we have a ready

means at our disposal to correct almost all sensory errors. We need merely be careful to check the

reports given by one sense against those given by the others and assent only

to those reports that all the senses agree on giving. At the close of Meditations VI Descartes applied this claim to resolve the doubts

raised by the dreaming argument. He

claimed that as long as we bring all our faculties, particularly our memory,

to bear before making a judgment, we will discover that dreams contain

tell-tale discontinuities. When the

dreaming sequence starts, a whole scene just pops into existence without our

being able to tell where it came from or how we got to be there observing

it. Moreover, in dreams events

frequently occur that are in violation of established laws of nature. In

waking life, in contrast, there is continuity to our experience and a

rigorous obedience of events to natural laws.

Therefore, we need only consider whether our experiences are coherent

and regular in order to discriminate waking from dreaming experiences. Though it is not explicit, this argument most

likely depends on the same appeal to the goodness of God in not allowing us

to be deceived that all of the other doctrines of the second half of Meditations VI presuppose. It is logically possible that we could have

coherent dreams. It is also logically possible that we might dream that we

remember a coherent past to our current dream. Descartes seems to have rejected these

possibilities on the ground that God would not have made our memories

defective in any irremediable or undetectable way, and would not have allowed

us to have dreams that are so coherent as to be more than temporarily

undetectable. All this having been said, the concluding

sentence of the Meditations remains

worth quoting and considering. But because the need to get things done

does not always permit us the leisure for such a careful inquiry, we must

confess that the life of man is apt to commit errors regarding particular

things, and we must acknowledge the infirmity of our nature. In the end, absolute certainty in all things

is neither possible nor necessary. The

demands of daily life are often such as to prohibit taking the time for a

careful examination of whether all the senses, memory, and the understanding

agree on some point. As a consequence

we will continue to get things wrong.

The Meditations has not

provided us with a remedy for all error.

But, in Descartes’s estimation, it has at least

provided us with certainty about some very basic and foundational truths, and

so a secure foundation on which to build the rest of our knowledge, fallible

though that superstructure might turn out to be. CARTESIAN

DUALISM One of the most serious challenges faced by

the Cartesian philosophy concerns the nature of the mind/body union and the

manner in which mind and body might interact with one another. Critics have charged that it is impossible

to understand how the mind is able to move the body or the body able to cause

the mind to experience sensations, and that it is impossible to understand

how two such radically distinct substances could be welded together to form

the “substantial union” Descartes spoke of in Meditations VI.

This problem becomes particularly acute in

connection with Descartes’s attempt to resolve the

problem of sensory error. In that

attempt, he maintained that since the mind is unextended and the body

extended, there must be just one place within the body where the two communicate.

Earlier, this claim was defended by appeal to experiments with

amputations. But these experiments

only provide partial confirmation of Descartes’s

position. Were I to have a stroke, or

were a part of my brain to be amputated, I would sense that I had lost a part

of my mental capacities. This suggests

that the mind may be connected with the body at more than just a point, and

that severing off parts of the brain may be tantamount to severing off parts

of the mind. Hobbes’s materialism took this consequence to

its logical conclusion: simply deny that there is any such thing as mind and

attempt to account for all the characteristic mental functions by reducing

them to operations of the brain. Those who have been unwilling to accept either

of these radical solutions are called dualists, because they follow Descartes

in holding that mind and body are two distinct kinds of thing, neither of

which is reducible to the other, and they have inherited Descartes’s

problem of accounting for how the thing in us that senses, thinks, and wills

could interact with the body. Among

the solutions to this problem that dualists have come up with are Leibniz’s

pre-established harmony, Spinoza’s double aspect theory, and Malebranche’s occasionalism.

According to the theory of pre-established harmony there are both

material and spiritual things, but neither interacts in any way with the

other; rather, like two clocks that independently tell the same time, each

evolves over time in accord with its own internal principles, but does so in

such a way that changes in the one just happen to be completely in accord

with changes in the other. According

to the double aspect theory, there is really only one substance, but this

substance appears to us in two different ways depending on whether it is

considered through the senses or through the intellect; therefore, mind does

not interact with body; there is just one thing that changes over time and

that appears in one way as a body in motion (when viewed using the senses)

and in another way as a mind with ideas (when viewed using the

intellect). According to the theory of

occasionalism, God is constantly inspecting minds

and bodies, and on those occasions where particular motions occur in the

sensory parts of the brain, God causes the mind to experience corresponding

ideas of sense, whereas on those occasions where particular volitions occur

in the mind, God moves the body in corresponding ways. Descartes’s own position on this

problem is difficult to make out. While some of his remarks might be taken to

suggest a commitment to occasionalism, his claims

that when God made us he mixed two distinct substances to form a substantial

union, and that the mind is naturally so constituted as to receive certain

sensations as a consequence of affection of the corporeal imagination,

suggest that he may have held that there is some sort of real causal

interaction between the mind and the body.

But since the interaction cannot take place at many points without

treating the mind as coextensive with the brain and reverting to Hobbist materialism, the one-point interaction theory

appears to have been Descartes’s only remaining

option. The precise nature of his

position continues to be a matter of dispute among commentators. SUBSTANCE,

REAL QUALITIES, AND THE EUCHARIST One of the most serious difficulties with

Descartes position in the Catholic France of his own day concerned the threat

his philosophy was taken to pose for the doctrine of transubstantiation and

the theology of the Eucharist. Unlike

the more internal, enthusiastic and iconoclastic forms of Reformed

Protestantism dominant in England and Holland, Catholicism tended to place

emphasis on a more external, ritualistic form of worship, involving beliefs

and ceremonies that the Protestants denounced as absurd and

superstitious. One such element was

the ceremony of the Eucharist, where, in imitation of events reported to have

taken place at the “Last Supper” between Jesus Christ and his disciples, a piece

of bread and a goblet of wine are supposed to be literally (not just

figuratively or metaphorically) turned into the body and blood of Christ,

despite continuing to look to all appearances like bread and wine. The Protestants had maintained that Christ

should be understood to be only spiritually present in the bread and wine,

but the Catholics had denounced this as a patent heresy. Christ had reportedly said “This is my body

… this is my blood.” The Catholics took

this to be meant literally. And they

insisted that ordained Priests acquired the power to re-enact this miracle

during their religious ceremonies. Of

course, the bread and wine continue to look and taste like bread and wine,

even after the miracle has been performed (though there were, of course,

occasional reports of more literal sightings). But, according to the Catholics, they have

really been transformed or “transubstantiated,” notwithstanding the

appearances. This belief was

underwritten by the Aristotelian notions of substance and real quality. At the moment when the priest “consecrates”

the bread and wine, it was thought that the essence or substantial form of

the host changes from that of bread to that of the body and blood of

Christ. However, all the merely

“accidental” qualities that were previously evident in the bread and wine

continue to be there (which is why it still looks, feels, tastes, and smells

the same). However, these qualities

subsist outside of any substance (the substance of Christ’s body and blood

was not supposed to take on these accidental qualities but to exist apart

from them). Crucial to this

explanation of the miracle is the notion that sensible qualities like colour,

smell, and taste, are real qualities that exist outside of us and that can

even exist apart from the substances in which they normally inhere. Even more interestingly, this was taken to

extend, not just to the sensible qualities of smell, taste, and colour, but

also to the extension, shape, size, motion and solidity of the bread and

wine. The substance of Christ’s body

was supposed to exist distinctly from the particular extension of the bread

and wine, a detail that allowed the Catholics to maintain that the whole of

the body of Christ could be present in even very oddly shaped small fragments

of the bread and wine. Insofar as the Cartesian philosophy is

unfriendly to the existence of real qualities, it is unclear that it can

countenance the miracle of the Eucharist.

This is a problem that was raised by Arnauld

in his fourth set of objections to the Meditations. Arnauld wrote: But what I see as likely to

give the greatest offence to theologians is that according to the author’s

doctrines it seems that the Church’s teaching concerning the sacred mysteries

of the Eucharist cannot remain completely intact. We believe on faith that

the substance of the bread is taken away from the bread of the Eucharist and

only the accidents remain. These are extension, shape, colour, smell, taste

and other qualities perceived by the senses. But the author thinks there

are no sensible qualities, but merely various motions in the bodies that

surround us which enable us to perceive the various impressions which we

subsequently call ‘colour,’ ‘taste’ and ‘smell.’ Hence only shape, extension

and mobility remain. Yet the author denies that these powers are intelligible

apart from some substance for them to inhere in, and hence he holds that they

cannot exist without such a substance. … Further, he recognizes no

distinction between the states of a substance and the substance itself except

for a formal one; yet this kind of distinction seems insufficient to allow

for the states to be separated from the substance even by God. Questioning the mystery of the Eucharist was

something that Descartes wanted, at all costs to avoid. Two paths were open to him. One was circumspection of the sort we have

seen him recommend to Regius, cited at the end of

Chapter 7. Taking this path would mean

refraining from denying outright that sensible qualities are real

things. It would mean instead

maintaining that while we have excellent reasons for concluding that external

objects must be extended and so must possess the modifications of which

extension is capable, we do not have the same reasons to think that they must

have any other sort of qualities. They

might possibly have further qualities, though we have no need to suppose any

other such qualities when giving scientific explanations. If we accept that bodies have further

qualities, it is not because we very clearly and distinctly perceive that

they must but only because this is a truth that has been revealed to us (by

the Biblical account of the last supper and the accepted theology regarding

the Eucharist in particular). We might

think that Descartes had good reasons to take this path, because the

arguments of Meditations VI are

simply not strong enough to give us reason to deny the existence of real

sensible qualities. Those arguments go

so far as to assure us that bodies must have the primary qualities of

extension and motion, but they do not rule out the possibility that bodies

might turn out to have other qualities as well. At best, they tell us that we are in no

position to know this without the assistance of revelation. But in the end, this was a path that Descartes

could not take. Allowing for even the

possibility of the existence of real qualities would undermine his physics,

which was invested in the notion that bodies can have no other qualities than

those that arise from extension. So

Descartes took a different route. He

attempted to reconcile his philosophy with the doctrine of

transubstantiation. His reply to Arnauld invoked a distinction between the “superficies”

or outer surface of a body (including all its pores, if it has them, or the

outlines of all of its parts, if it has independently movable parts) and the

material contained within this superficies.

The latter could change while the former remains the same he

maintained. But were this to happen,

the body would continue to affect our sense organs in the same way, and so

bring about the same sensations in us, even though it is constituted of

material of an entirely different kind (that is, even though its ultimate

parts are differently shaped and moving).

This, in his estimation, constitutes a far more intelligible

explanation of the primary doctrine, that of transubstantiation, than that

offered by the Scholastics with their commitment to real qualities. It preserves the essential tenet that the

substance changes while the way it acts on us remains the same, at the same

time avoiding the Protestant heresies on this topic. This did not go all the way to resolve the

problem, however, and it was not intrinsically very satisfying. It did not account for how an extended

substance could be separated from its modes of size, shape, and motion, which

was also a part of the doctrine, and it raised questions about how far the

substance could have been really transformed if it continued to occupy the

same superficies, given what Descartes had to say about how extended

substances are distinguished from one another. When pressed on these issues, Descartes

became very reticent to go into detail, and turned to the claim that it is

union with a mind that really makes a human substance the kind of thing it

is. The same would have to hold of the

substance of Christ insofar as it shares any physical nature. However, this was all too close to the

Protestant view that Christ is merely “spiritually” present in the

sacrament for comfort, and Descartes

knew it because he asked those to whom he had revealed these speculations to

not reveal his identity. Mesland, a Jesuit who corresponded with Descartes about

these topics and who may have made some moves in the direction of getting Descartes’s philosophy endorsed by the Jesuits, was sent

off to the missions in ESSAY

QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Over the course of the

Meditations, and particularly over

the second half of Meditations VI,

Descartes frequently invoked the term, “nature,” and discriminated a number

of different kinds of “nature” and senses in which he wanted the term,”nature” to be understood. “Nature taken generally” is defined at AT VII 80, but there is another definition of “nature

taken more narrowly” at AT VII 82. Descartes outlined correspondingly

different accounts of what is “taught by nature” in each of these senses and

what is taught to us by “a certain habit of making reckless judgments.” At AT VII he also

contrasted what has been “taught by nature” with what is known in the “light

of nature.” And over AT VII 84-85 “nature” is used again in a “latter” and a

“former” sense that do not bear any obvious relation to either the “general”

or the “narrow” definitions of “nature.”

Taking all of these passages into account, formulate a general account

of Descartes’s position on “nature” in all of its

senses. Determine whether he managed

to clearly separate the different senses of the term.

2. Did Descartes have any

principled way of distinguishing between what is “taught to us by nature” and

what is taught to us by “a certain habit of making reckless judgments” or is

this distinction irredeemably confused and ambiguous?

3. Undertake a study of Descartes’s correspondence and that of his contemporaries

in order to determine exactly what problems he got into over the issue of the

Eucharist and why.

4. One of Descartes’s most astute critics was Princess Elizabeth of

5. Undertake a this same project with reference to Descartes replies to

the author of the fifth set of the objections to the Meditations, Pierre Gassendi.

6. Did Descartes come up

with an adequate response to the dreaming argument? |