|

16 Cartesian

Science (Principles

of Philosophy II.3-23, 36-40, 64; Discourse

V [AT VI: 40-46]; Principles IV.196-99, 203-4; Discourse VI [AT VI: 63-65])

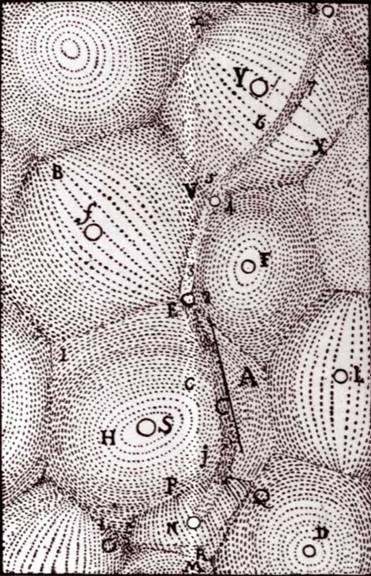

In Discourse

V, Descartes claimed to have accounted for all the phenomena of nature on the

basis of just these principles: the creation of stars and planets, of the various elements and

minerals on Earth, for light, fire, gravitation, magnetism, and even for the

evolution of living bodies. In developing this account, Descartes’s

first project was to determine what the laws of motion and collision

are. Applying these laws to a universe

that is everywhere full of matter led him to develop explanations of natural

phenomena that made heavy use of the notion that matter is swirling around in

vortices. Matter has to swirl around

since there is no empty space for it to move into. This means that motion can only occur

through material parts giving way by moving into the places left behind by

the bodies they give way to, that is, by having things move around in closed

loops. However, he recognized that he

was only able to discover the most general things simply by deduction from

metaphysical first principles. When it

comes to accounting for the specifics of how bodies interact, experience has

an important role to play. At the close of the Principles, having, as he believed, successfully shown how all

the phenomena of nature could be explained by mechanical principles,

Descartes returned to the topic of sensible qualities, and offered a final

set of reasons for concluding that these qualities should not be attributed

to material things. QUESTIONS

ON THE

1. What is

hardness, as far as our senses are concerned?

(This question and the following two are on the reading from Principles II.)

2. Why must the

quantity of motion in the universe be preserved?

3. Is it natural

for bodies that have been set in motion to slow down and stop? What is it that teaches us the answer to

this, sense experience or understanding?

4. Are there any

random or chance occurrences in nature, according to Descartes? (This question and the following two are on

Discourse V.)

5. In giving his

account of the nature of matter in Discourse

V, what features or properties did Descartes explicitly identify as ones he

had no use for and did not need to suppose matter to have?

6. How did

Descartes respond to the objection that it is contrary to the creation story

of the Bible to suppose, as he did, that all God needed to do to make the

solar system, the Earth, the arrangement of water and minerals on the Earth,

the weather, and the life on Earth, was institute certain laws and set an

originally chaotic arrangement of matter in motion?

7. What do the

nerves transmit to the brain? (This question and the following three are on

the reading from Principles IV)

8. Where does the

feeling of titillation or pain, and the appearance of light and sounds

originate?

9. What makes it

unlikely that the colours we sense are produced by colours actually existing

on the surfaces of bodies? 10.

What is the major guide Descartes relied upon when

deciding what hypotheses to formulate about the workings of the small parts

of nature? 11.

Is there a role for experimentation in Cartesian

science, and if so what is it? (This

question is on the selection from Discourse

VI.) NOTES

ON THE Principles II.3 opens where Meditations VI left off, with the

assertion that sensations were only given to us to reveal what is good or bad

for the mind/body union, not to discover the essences of material

things. That is to be done by pure

understanding alone. And that is what

Descartes proceeded to do: to consider what pure understanding itself tells us about bodies. When we do that, he claimed, we don’t just

discover what we have already learned, that our ideas of sensible qualities

might be materially false ideas of nothing whereas extension is something

positive and real that constrains our thoughts to conform to the laws of

geometry. We further discover that

there is nothing aside from extension that bodies cannot be conceived to

lack. Recall that Descartes has maintained

that if it is possible for us to conceive one thing without thinking of

another, then it must be within the power of God to create the one thing

without the other. So if we can

conceive bodies without particular qualities, they must be really distinct

and separable from those qualities.

This is certainly the case with taste and smell, as there are

tasteless and unscented bodies, and it is even the case with colour as there

are transparent bodies, like glass and air.

It is even the case, Descartes claimed, with qualities like weight and

hardness. Pulverized stones do not

feel hard, and if all bodies retreated from our hands as we approached them

we would have no sensations of weight or hardness, even though those bodies

might exist. It is only extension that

is essential to bodies, he claimed. But might the very argument Descartes

used to deny that bodies have any other qualities also be applied to

extension itself? We discover by experience

that different materials have a different weight to them even though they

take up an equal space. It is more

difficult to lift or throw a cannon ball than an equally sized wooden

ball. And same quantities of some materials,

like air or like the wax of Meditations

II, might be compressed into a smaller volume in a piston cylinder or

observed to expand when heated. (It is

not as if the wax gets puffed up by the insertion of fire particles because

when you put it on a scale it retains the same weight.) This evidence would appear to indicate that

even the extension can change while the body remains the same and so that

body might be something more or other than extension. This is why, Descartes claimed, the “subtlety”

(i.e., the overly refined thought) of some people had led them “to distinguish

the substance of a body from its quantity, and even its quantity from its

extension” (Principles II.5). These people would take the weight or mass

of a body to measure its quantity and distinguish the quantity from the

extension that quantity takes up, and they would use a measure of quantity

per unit of volume or extension to distinguish different species of material,

like gold or lead, from one another.

(Hence, the term “specific gravity” which refers to how much equal

volumes of different materials weigh, and which is used to distinguish

elements.) Descartes would have none of this. He wanted at all costs to deny all other

qualities, even mass and solidity, of body, and maintain that the only

qualities it possesses are those which arise from the way its spatial

extension is modified. To this end he

declared that the phenomena of rarefaction and condensation (or expansion and

contraction) and of differences in mass per unit of volume can all be

explained simply by supposing that bodies contain pores, which can be

inflated by an ingress of other bodies, like balloons, or collapsed into one

another, like crushed honeycombs. What

we experience as weight is simply the motion of bodies in a particular

direction, and the resistance of those bodies to changes in motion. If equally sized bodies seem to have different

weights, it is only because the lighter one has larger pores, which means

that there is less of it moving in a particular direction while surrounding

bodies pass through its pores unmolested.

Think of swinging a sieve through the air and swinging a frying pan

through the air. The sieve and the

frying pan look to be the same size only because the sieve is full of holes,

and the sieve moves so much more quickly and easily because there is actually

so much less of it to move, and the surrounding bodies do not get caught in

its pores and carried along with it, but merely pass through it as it goes on

its course. Were the sieve compressed

so that its parts all come into contact with one another, it would be seen to

take up much less extension than the frying pan. To back this speculation up, Descartes

claimed that it defies our understanding to explain the rarefaction or

condensation of materials in any other way.

More rare or lighter bodies must have been made lighter by having

their stuffing knocked out of them, leaving holes behind (albeit holes that

get filled with surrounding materials flowing through them, rather than holes

that are conceived as absolutely empty spaces). And more weighty or massive ones must have

had their architectural vaults and caverns either crushed and collapsed or

stuffed with more of the same material. There is simply no other way to understand

rarefaction or condensation, Descartes claimed, than through the addition and

subtraction of parts. To become

lighter is to lose something, to become heavier to gain something. That thing could only be a quantity of

matter which is extracted or inserted.

The quantity of matter therefore cannot be separated from the quantity

of its extension — not if you are careful to subtract the false extension of

the holes or pores, which are not properly part of the body. In addition to supporting his claim that

body is nothing more than extension, Descartes offered more support for his

claim that all spatial extension is body.

The one does not automatically follow from the other. Even if bodies are nothing more than cut up

bits of space, it does not follow from this that wherever there is space

there is body. A body is a movable space, and it is a serious

question whether there might not also be an immovable space (often called

“place”) that stays where it is and so remains behind when a body moves away

from it. We do think this way about

places. We think that they stay where

they are, and we think that there is a kind of space that consists, not of

the extension of some movable body, but of the aggregate of places — a kind of infinite or indeterminately large

container. Descartes argued that this

latter notion is absurd. If we only

pay attention to what we very clearly and distinctly perceive in our idea of

an empty space, he claimed, we will see that the idea of an empty space is

the idea of a space that contains nothing, not even air or light or other

subtle material. But if an empty space

contains nothing, then to say that a certain space, say the space between the

walls of a vessel, is empty is to say that there is nothing between the walls

of the vessel. But if there is nothing

between the walls of the vessel, then they must be together. In other words, it is not merely

physically, but logically impossible that empty space or nothingness should

exist. We do speak of empty spaces all the

time. But in ordinary discourse, when

we speak of an empty space, we do not mean a space that contains nothing

whatsoever, but just a space that does not contain what it is supposed to

contain. Thus, a pond is said to be

empty when it contains no fish, even though it is full of water, and a bottle

is empty when it contains no water, even though it is full of air. Consider concave shape, Descartes said,

like the inside of a bottle. You

cannot conceive the concavity without conceiving there to be some extension

between the ends. To imagine a “C”

shape without imagining extension between the ends of the “C” would be like

trying to imagine an up-slope without a down slope. But all extension must be the extension of

something. An extension that was the

extension of nothing would be no extension at all. So it is impossible to conceive anything to

have a concave shape without at the same time conceiving something to fill

the concavity. Absolutely empty space

is simply unthinkable. Our views to the contrary are, Descartes

claimed, due to the fact that when we see a body move relative to certain

landmarks, we are still able to specify the original place of the body by

reference to the landmarks. This makes

us fall into the error of thinking that the place exists independently of the

body that was in it. What really happened

was that the body moved away, carrying its space with it, and was replaced by

some other body, carrying its own extension.

But, because the replacement body occupies the same position relative

to the landmarks, we think of the replacement as being in the same place and

imagine that the place exists independently of either body. Then we concoct the idea of immovable space

as the aggregate of places. But in

fact place is not a real thing, but a mere relation. Suppose, as seems necessary, that space is

infinite in extent (the notion of a boundary to space seems absurd so Descartes

felt confident claiming this is clearly and distinctly perceived to be

impossible). Then beyond any bodies

taken to be landmarks there will be yet other bodies, relative to which the

first set of bodies are moving. In

that case there would be no ultimate landmarks relative to which places could

be defined. Places are merely

artifacts of our choice of which bodies to take as landmarks and exist only

as a consequence of that choice and not independently. Our belief that empty space might exist

arises another, rather less sophisticated source. As Descartes himself noted, we consider it

at least possible that some of our sensory ideas, like those of cold or the

colour black, might be “materially false” ideas that represent nothing as if

it were something. We consider that in

these cases there may be no bodies in the space around us, and that the sensations

we experience are not so much real, positive sensations as the state our

sensory awareness is left in when there is nothing around us that stimulates

our senses. But this is just a “juvenile

preconception,” or hasty judgment, Descartes objected. Just because our sense organs are not being

stimulated by anything around us it does not follow that we are not still

surrounded by bodies. The bodies may

just not be of the sort that affect our senses. We know there are transparent stones,

tasteless and odourless air, and many bodies that are too small or soft or

close to our own body temperature to affect our touch, and air can have all

of these qualities even though a puff it is sufficient to set a huge sailing ship

in motion, proving that it is still something and not nothing. So we have no justification for taking our

experience of spaces where there is nothing that stimulates our senses to be

evidence for the existence of empty space. Descartes took the fact that there is no

empty space to entail that all motion must be the rotary in nature. After all, if the world is full of body,

then the only way anything can move is if a whole ring or sphere or cylinder

or other cyclical form rotates. This

in turn entails that matter would have to be infinitely divisible. In a universe composed of a solid mass of

cubes, motion can occur as long as the cubes slide past one another in a

line. But if the cubes must move in a

curve, they could not pass one another without creating gaps, that is, empty

spaces. Since that is impossible, the

pieces of extension must constantly be bending and breaking as they move past

one another, in order to generate little pieces to fill the interstices that

would otherwise form, and these pieces must be arbitrarily small. (Principles

II.20 offers a different, less self-serving reason for believing that bodies

must be infinitely divisible: Since any body must be extended, and what is

extended has sides set outside of one another, it must be at least possible

for God to separate one side from the other.)

Consistently with his rejection of

vacuum, Descartes also claimed that rarefaction and condensation (expansion

and contraction) must be due to the entry or exit of foreign bodies into

inflatable and compressible chambers within the circumference of a body, and

that it must only be possible to compress bodies down so far (to the point

where all the foreign matter has been squeezed out of their chambers and

their walls are completely collapsed.

Differences in the mass and density of different materials, like equal

volumes of lead and wood, are not due to the fact that these bodies have

different weights or masses, but are rather due to the fact that they are

more or less porous. Wood has large

pores through which more subtle matter readily flows and when we go to move

it, it looks like we are moving a solid volume, but really we doing the

equivalent of moving a sieve through the air.

There is really not that much material there to move. Lead has smaller pores and that is why it

is harder to move. There is actually

more of it in the space, and more effort is required to set all of that

material in motion. Descartes’s physics also appealed to the

principle that God is supremely constant in all of his operations. Descartes took this to follow from the

perfection of the Divine nature. An

all-perfect being would not change his mind, since that would show

indecision, uncertainty, or lack of foresight. This is not to say that God never does

different things in different times and places. He created a universe containing various

things, differently shaped and moving in different directions. But Descartes insisted that unless

well-verified sense experience or revelation inform us to the contrary, our

default assumption should always be that God keeps working in the same way. God’s constancy needs to be combined

with the doctrine of constant creation.

Recall that according to that doctrine God must constantly recreate

the world from one moment of time to the next. Since it is of the nature of time that the

past no longer exists, a bare tick of the clock, meaning that the present

moment has become past, signifies that everything that now exists has been

annihilated. It must, therefore, be

recreated in order to be sustained in existence. God is constantly doing this. This is the doctrine of constant creation. But now we need to think that God is

supremely constant in all his operations.

Combining these two doctrines yields the result that in recreating the

world from one moment to the next, God will conserve everything, recreating

each body that existed at the previous moment and putting into it just those

modifications it possessed at the previous moment. Among these modifications would be a state

of motion, and Descartes thought that having once injected a certain quantity

of motion into a body God would recreate that motion from moment to moment in

an unchanging way, just as he would recreate the body itself. This means conserving both the direction

and the speed of the motion and so recreating the body just slightly further

down on a straight line path. The

effect of this operation is to underwrite what was later called the principle

of inertia: the principle that each body in the universe, once set in motion,

will continue in that motion in the same direction and at the same speed,

unless something special happens to alter that state. Descartes recognized one such special

cause of a change of motion: collision.

From time to time, as a body moves, it will run into other bodies

standing in its path. (Indeed, in a

plenum, that is, a world that contains no void, this will happen in no time

at all.) When running into an

impediment, the body cannot simply pass through, since we

very clearly and distinctly perceive that two different bodies cannot occupy

the same place at the same time.

Consequently it must either drive the impediment on in front of it, or

bounce back, or come to rest and transfer its motion to the impediment (or,

more precisely God must so recreate it), and whichever of these cases occurs,

the overall quantity of motion cannot be increased or diminished. Just which of these three cases occurs in

which circumstances is something Descartes thought he could deduce from the

constancy of the Divine operations.

The main point is that, on this scheme, the motions of the parts of

matter are rigorously determined by the laws of inertia and collision. The one exception to these rules concerns

the motions of those bodies that are united to finite minds (i.e., human

bodies). God is willing to move these

bodies in ways projected by the wills of the minds that they are attached to.

On the basis of nothing more than this

simple physics, Descartes proposed to explain the evolution of the solar

system from an original, chaotic state, the formation and burning of the sun,

the formation of the planets and evolution of the various minerals on earth,

and even the evolution of life and such physiological processes as the

beating of the heart and the circulation of the blood. All of these phenomena, he claimed,

originate from nothing more than the motion and collision of otherwise

uniform and undifferentiated particles of matter. There is no need to invoke forces of

impenetrability, chemical bonding, electromagnetic or gravitational

attraction, or notions of variations in mass, and certainly no need to

ascribe different sensible qualities to bodies. Here is how Descartes attempted to

justify his position. He supposed that the universe consists

of three different kinds of matter: gross matter (which goes to make up very

large bodies like the planets and the bodies on the planets like our own

bodies, the water, and the air), intermediate matter (which goes to make up

an extremely fine aether that fills the interstices between bodies and fills

the universe with vortices), and subtle matter (which goes to make up light). Intermediate matter is composed of very

tiny, approximately spherical bodies, and is the original form of

matter. Subtle matter is created when

the pieces of intermediate matter move and some of them break into extremely

tiny, spiky pieces that fill in the interstices that would otherwise form

between the subtle matter. Gross matter is composed of pieces of

subtle matter that get stuck together to form jagged, twisted shapes that

readily interlock with one another to form arbitrarily large chunks. Originally, when God created the

universe he just created intermediate matter in a very compact form (squashed

into cubes, as it were). But then God

injected a certain quantity of motion into the universe, and, being supremely

constant in his operations, he preserves this same quantity of motion through

the rest of time. The moving pieces of

intermediate matter quickly generate subtle matter, which generates stars and

suns, which in turn generate gross matter, which generates the planets and

the minerals, vegetables and animals on the Earth. As noted earlier, vortex mechanics is

supposed to take care of all the details. While Descartes paid lip service to the

Christian dogma that God spent six days creating the world out of nothing and

ordering all its parts, he also observed that God could have simply injected

a certain quantity of motion into a chaotically arranged mass of

particles. Simply as a result of the

necessities of vortex mechanics, systems of stars and planets, and worlds

like our own would very quickly evolve.

Be this as it may, he added that the doctrine of constant creation

makes it sufficiently evident that God is required to sustain the universe

from moment to moment, and indeed, make the laws of physics possible. So we need not worry that casting doubt on

the creation story will in any way damage the need to accept the existence of

God. One final feature of Descartes’s physics

deserves some consideration: its position on the role of experiment and

hypothesis. As so far described, Descartes’s

science proceeded in what might be described as an exclusively top-down

fashion. From metaphysical first

principles concerning the nature of God and matter, Descartes proceeded to

derive the laws of motion, to deduce the necessity of the existence of

vortices and the three main kinds of matter, and to account for the origin of

the general kinds of things: the Sun, planets, minerals, winds, tides, and so

on.

But Descartes noted that this

exclusively top-down procedure could not suffice to explain the nature and operations

of more particular objects, like the particular species of animal and

vegetable life. The reason for this is

that the first principles and what follows from them are too simple and

general. They tell us that everything

that happens must be the result of rolling vortices and the impact of

particles. But what vortices and

particles, moving in what ways? Just

as it is possible to compose an infinite variety of novels with the few

letters of the alphabet, so it is possible to account for the generation of

an infinite variety of different species of things from mechanical

principles. To discover what species

actually exist, as opposed to what ones might possibly exist, we need

recourse to experience. This is just one respect in which we

must have recourse to experience. When

we attempt to explain why particular species behave as they do, we find

ourselves not so much as at a loss for an explanation as overwhelmed with the

number of different possible explanations.

Just as it is possible to make clocks with many different arrangements

of gears and wheels that will all tell the same time, so it is often possible

to conceive of many different mechanical devices that could all produce the

same visible effect. Under these circumstances, Descartes thought

that we have no recourse but to consult our experience with the operations of

the larger-scale objects whose parts we can see, particularly machines of our

own invention. To understand the

operation of the muscles for instance, we must consider how we would

construct devices to alternatively draw strings together and release

them. We must then provisionally

suppose that some such machine is the one that actually produces muscular

motion. That is, we must formulate a

hypothesis. And then, if there are

rival, alternative hypotheses that both seem to be likely ways of explaining

the phenomenon, we must look for some respect in which they are different and

devise some sort of experiment that, when performed, would yield one type of

result when one machine is responsible, but another if a different one is

responsible. We must then choose in

favour of the machine that our experience of the results of the experiment

indicates. Of course, our hypotheses cannot be

wild: they have to conform to the things Descartes claimed to have

established so far. They cannot

involve postulating unextended bodies, forces, real qualities, or other

non-mechanical modes of explanation, and they cannot violate the laws of

motion or collision. But within these broad bounds, we are free to speculate

about precisely what mechanism may be producing the phenomena we observe. Cartesian science may accordingly be

viewed as a three-tiered structure. On the top tier is metaphysics and first

philosophy and all of the things we clearly and distinctly perceive. It is there that we do the exercise of the

Meditations and establish the fundamental principles of physics. It is there that we learn of the existence of

God, of the equation of body and extension, and of the laws of motion and collision.

On the bottom tier is sensory

experience. It is there that we learn,

more or less accurately, what particular sorts of objects there are in the

regions immediately around us and what sorts of effects these objects have on

us. It is experience that teaches us

such things as that there are planets that are carried in circles through the

constellations, that there are tides, that iron is attracted towards the

magnet, and that bodies that feel heavy in our hands tend towards the centre

of the earth. In between the top tier and the bottom

there is a gap. Descartes recognized

that science cannot proceed in a purely top-down fashion to derive all the

particular features of the world from general principles. From first principles we can only carry our

deductions so far, to draw conclusions about general laws and

structures. After that, we must go

down to the sensory level, accept what it tells us about what the particular

phenomena of nature are, and construct hypotheses that connect the general

principles found at the top level with the phenomena observed at the sensory

level. These hypotheses must be

consistent with the general principles and of such a nature as to allow us to

see how the specific phenomena follow.

But because there will typically be alternative, rival hypotheses, all

apparently capable of connecting the general principles with the observed

phenomena, we cannot simply accept the hypotheses as statements of the truth

of the matter. We instead have to rely

on sensory experience of the results of crucial experiments to help at least

narrow down the range of alternative hypotheses. The middle tier of Descartes’s system,

the tier where the gap in the deduction occurs and at which hypotheses are

made, is therefore simultaneously determined by both the lower and the upper

tiers. The hypotheses that are arrived

at must be consistent with the principles discovered at the upper tier, but

it is the lower tier that tells us what these hypotheses have to explain, and

it is the lower tier that judges their adequacy. In this way, we might hope to eventually

arrive at the correct hypothesis. Physiology and the phantom limb. The selections we have read from the Principles close with a further argument for the ideality of sensible qualities (IV.196-198). This concluding argument is more ambitious than any we have encountered so far. It does not just establish not that sensible qualities are not essential to body or that body is really distinct from sensible qualities, but that it is most likely that they only exist in us and not in bodies. This argument depends on experience, but not experience of things like transparent stones, where body is experienced apart from sensible qualities. It instead appeals to cases where sensible qualities are experienced apart from bodies. Descartes cited the example of amputees who report feeling pains that they experience as being located in a limb that does not exist. By itself, this suggests that the pains these people are feeling are not located where they think they are, but are in fact only in their minds. Nor is this a special case. Like Hobbes, he appealed to the case of people who are struck in the eyes and see light, and he also mentioned the case of people who stop their ears and hear a roaring sound. In all of these cases, the qualities that are experienced are only in the mind and not located where they are perceived as being located. Thus, experience itself reveals to us that these sorts of judgments are mistaken. By itself this is not a very compelling argument, because the same point could be made about experiences of shape, size and motion, which Descartes wanted to say are not merely ideas in us but qualities of external objects. However, there is more to be learned from these sorts of cases than just that we might sometimes be wrong in supposing that there is anything outside of us that resembles what we are currently experiencing. When we inquire into the cause of these experiences by doing some anatomy, we discover the existence of nerves leading from the sense organs to the brain. We further discover that what leads us to experience sensations is impact on or pulling of these nerves at any point along their length. The reason the amputee feels the phantom pain is that the nerve that used to lead to that part of the limb is affected. This led Descartes to infer that when God unified our minds with our bodies, he set things up in such a way that the mind, which is not extended and nowhere in space, would communicate with the body from a certain point in the brain. Information about what is happening in the body would have to be communicated to the mind by nerves extending from the brain to the various parts of the body, inevitably creating the possibility of misperception when these nerves are affected by a disease or some other intrusion along their length, rather than stimulated by objects touching their far ends. God would have set things up so that, in the normal case, where an internal bodily state affects an internal nerve, or an external object touches the end of a nerve that reaches out to the skin or a sense organ, we form in our minds an appropriate sensation. Descartes had one final point to make before launching his capstone argument: when we inspect the nerves that proceed from the different sense organs, we do not find any evident differences between them. We don’t see visual nerves being stained by colours, or auditory nerves vibrating with sounds, nor find any differences in the nerves that might account for how they convey different sorts of qualities up to the brain. We don’t find, for instance, that the olfactory nerves are tubes for the conveyance of scented air or that fluids flow through the nerves from the tongue to convey tastes to the brain. Instead all the nerves look the same, like cords, and they are all affected in the same way, by being touched or pulled. Touch or pull an optic nerve and the subject sees a flash of light. Touch or pull a nerve on one part of the tongue and the subject tastes salt. This means that we can’t be experiencing sensible qualities because our nerves are conveying those qualities to our brains. Instead we are experiencing them because we were designed from birth so that, when certain sensory nerves are stimulated, we experience certain sensible qualities. What stimulates the nerve in these cases is not a sensible quality. It is instead a motion of some sort. But if bodies only stimulate the nerves in virtue of touching them, then it would be extravagant were they also supposed to be coloured, or hot or cold, or saline, or acidic, etc. Such qualities, were bodies to possess them, would serve absolutely no purpose in nature. They would not affect us insofar as they had such qualities. They would only affect us insofar as they have shape, size, and motion and impact on our sense organs. And, in all likelihood, they would not affect one another insofar as they had such qualities either. Experience itself teaches us, therefore, that we are in no position to affirm that bodies possess sensible qualities. All that we can be sure of is that we experience these qualities when our nerves are affected by bodies. Descartes’s developmental psychology. We might wonder why Descartes waited until the very end of the Principles before advancing his best and most powerful argument for denying the external reality of sensible qualities. The answer is that the argument presupposes the existence of an external world of extended and moving things, the existence of our own bodies, an account of how our minds are united with our bodies, and an account of all the phenomena of nature that succeeds at making it plausible that all these phenomena are produced only by the shape, size, motion, and impact of bodies. It was only at the end of the Principles that Descartes was in a position to claim that he had done all of these things. In the Meditations the best he could do was make unjustified assertions. Elsewhere, Descartes attempted to buttress this negative argument with an explanation of why people assume that sensible qualities exist in bodies. This explanation is rooted in a kind of developmental psychology, presented in the opening paragraph of a brief discussion of the principal causes of error, with which Part I of the Principles concludes. According to the account, when we began life as infants we experienced ideas of shapes and ideas of sensible qualities separately. The shapes we saw and felt were colourless and without tangible quality, and the colours and tactile sensations we experienced were aspatial and unordered. We considered these sorts of things, and indeed all our sensations, to be merely qualities of our own thoughts. This changed when we began to move around. We then noticed a distinction between those things we carry around with us wherever we go and those that remain behind when we move away. Principal among these things are shapes, which remain where they are relative to other shapes when we move our eyes or heads or bodies. So we came to distinguish shapes from ourselves and to consider them to exist apart from us. However, a further experience led us identify shapes with colours and other sensible qualities. This is the experience of only encountering particular sensations when in the presence of certain shapes. As a consequence of this experience, we first came to think of the shapes as being the causes of the sensations, and then to think of them as having the same qualities as the sensations (supposing that the cause must be like its effect). Indeed, we went so far as to consider the sensible qualities to be more real than the shapes, and to consider things that are merely extended without affecting our senses much (e.g. air) to be less real than those that affect our senses more. We also supposed that objects have exactly those sizes and shapes they appear to have (for instance, that the Earth is flat, and the heavenly bodies small.) It was only later that we learned the error of many of these opinions, and by that time they had become so entrenched in our thought that they have persisted, despite our knowing better. Thus, just as we continue to “see” (that is, judge) the Sun as orbiting around the Earth and as being only a few feet across, even though we know better, so we continue to “see” (that is, judge) colours to be on the surfaces of bodies and pains to be located in body parts — the only difference is that we have become so blinded by the latter preconception that, despite having once been able to see shapes apart from colours or other sensible qualities, we are no longer able to do so, even though we know better. This error is compounded by the fact that we find it difficult to think about things that cannot be readily sensed or imagined. So, though we could do analytic geometry (which Descartes invented) and in this way come to think of the objects of geometry in terms simply of numerical formulas and avoid reliance on visual diagrams (which always import the unnecessary element of colour), we find it too hard to do so and revert to what is sensible. A further problem is that we have a tendency to think by making use just of the words we use to name ideas, and perform calculations with these words rather than recover and inspect the ideas that they name. This introduces the possibility of ambiguity and equivocation, as words can drift away from the ideas they were devised to name and so mislead us by leading us to think of the wrong thing or confuse things that are really distinct. ESSAY QUESTIONS

AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Descartes’s

position that there is no such thing as space, but just extended bodies in a

plenum, was challenged in his own day by Pierre Gassendi,

and in the generation after by Isaac Newton.

Both Gassendi and Newton maintained that

space is something in its own right, that would continue to exist even if

bodies were annihilated, and Newton maintained that an “absolute space” (a

space that is not defined relative to bodies but is supposed to be separate

from them and immovable) must be presupposed as an ultimate reference frame

for inertial motion.

2. Descartes’s

position that the essence of body consists just of extension, so that

whatever other real qualities a body might in fact have are ones that would

have to be merely accidental to it and that it could stand to lose without

ceasing to be a body, was in perfect accord with the mechanistic outlook of

the early seventeenth century, but it was challenged in the later part of the

century. Locke maintained, in

opposition to Descartes, that bodies must have a real quality of solidity in

addition to extension.

3. Leibniz’s view

that repulsive force is responsible for the transmission of motion upon

impact naturally led him to suppose that collisions would always have to be

elastic. This is turn led him to

attack Descartes’s account of the laws of collision on the ground that they

violate a fundamental metaphysical principle, the law of continuity. Outline Descartes’s account of the laws of

collision as stated over Part II, Articles 46-53 of his Principles of philosophy

and Leibniz’s critique, given over Part II, Articles 46-53 of his “Critical

remarks on Descartes’s principles.”

4. In Part II,

Article 36 of his Principles of philosophy Descartes maintained

that the same quantity of motion is present after collision as before, so

that quantity of motion is conserved through collision. Leibniz objected to this view, maintaining

that it is rather the quantity of moving force in bodies that is conserved

through collision. (The moving force

or “vis viva” is another of the

forces Leibniz attributed to bodies.)

Descartes considered the quantity of motion to be the product of the

quantity of matter and its speed, a formula very close to that |

|

|

|

Cartesian

science is built on the foundations Descartes had established by the close of

the Meditations:

Cartesian

science is built on the foundations Descartes had established by the close of

the Meditations: