|

18 Locke, Essay Epistle and I.i.1-4,6-8;

I.ii.1-9,12,14-16; I.iii.1-6,9,22,24-25; I.iv.1-5,8-9,24-25 Innate Ideas

–

Locke, Essay I.iv.25 Though John Locke’s Essay concerning human understanding appeared three years after However, another, much more significant factor

behind the positive reception of Locke’s work was its agreement with the

increasingly republican and anti-authoritarian political views of the

day. Unlike Descartes, Locke was not

primarily motivated to write his book on human understanding in order to

provide a justification for a certain kind of philosophy of nature. Instead, he was motivated by social,

religious, and political concerns. The

introductory Epistle to the Essay

contains a famous allusion to these concerns.

Were

it fit to trouble thee with the History of this Essay, I should tell thee,

that five or six Friends, meeting at my Chamber, and discoursing on a Subject

very remote from this, found themselves quickly at a stand, by the

Difficulties that rose on every side.

After we had a while puzzled our selves, without coming any nearer a

Resolution of those Doubts which perplexed us, it came into my Thoughts, that

we took a wrong course; and that, before we set our selves upon Enquiries of

that Nature, it was necessary to examine our own Abilities, and see, what

Objects our Understandings were, or were not fitted to deal with. [Epistle, Nidditch 7, Winkler 1-2] James Tyrell, one of the “friends” present at

this famous meeting, later reported that the subject of discussion had not

been any topic in natural philosophy, but rather the principles of morality

and revealed religion. It was the

foundations of our knowledge of these topics that Locke was most concerned to

investigate. And Locke made no secret

of the conclusions he hoped to draw from that investigation. Rather than establish a particular doctrine

beyond any hope of contestation, Locke hoped that, by clearly drawing the

bounds between what it is actually possible to know and what can only be

entertained as a matter of opinion he would, “prevail with the busy Mind of

Man, to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its Comprehension;

to stop, when it is at the utmost Extent of its Tether; and to sit down in a

quiet Ignorance of those Things, which, upon Examination, are found to be

beyond the reach of our Capacities,” avoiding “Disputes about Things, to

which our Understandings are not suited” in favour of a general toleration of

the contrary opinions of others (I.i.4). For Locke, doing this was not tantamount to

arguing for scepticism or discounting the efficacy of all of our knowing

powers. He considered that there are

things that we can know, many of them concerning the moral matters of most

concern to us. By drawing the

boundaries between what can be known and what cannot he hoped to avoid the

sceptical funk that people often fall into when, having carried their

researches beyond anything they can hope to achieve and gotten nowhere, they

turn in disgust to the contrary opinion that nothing at all can be known. But he also hoped to prevent people from

disputing about things that we cannot hope to know for sure to be true and

mount a powerful argument for toleration of the contrary opinions of others

in cases where knowledge is beyond our reach and the best we can manage is to

form opinions. The general project of examining what things

our understandings are and are not capable of coming to know is one that

Locke found to be hindered, rather than helped, by the philosophy of

Descartes. Despite his avowedly great

concern to proceed from absolutely certain first principles, and not accept

anything that he could not clearly and distinctly perceive to be true,

Descartes was not very reflective about his own understanding or about the

other operations of his mind, such as imagining, willing, judging, and

believing. As has been noted in past

chapters, Descartes never really paused to consider how he could tell a clear

and distinct perception on the part of the understanding apart from a natural

instinct, or either apart from a hasty judgment. He had more or less simply helped himself

to these notions, as if they were patently evident. As far as Locke was concerned, this was

tantamount to an open invitation to others to do the same, and base their

most fondly cherished beliefs not on reasoning or evidence, but the bald

affirmation that these beliefs are patently evident to the understanding,

innately known, or divinely inspired through a special gift of Grace,

illuminating the understanding with a power it could not resist.

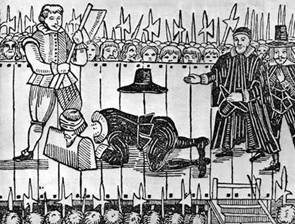

The natural concomitant of “enthusiastic”

religious practices was a belief in the priesthood of all believers (or at

least, those among them — the “Saints” — who had been elected for salvation

and chosen by God to receive his Grace).

These practices and beliefs were inimical to all forms of authority,

be they ecclesiastical, civil, or military.

The Tudor and Stuart monarchs in Apprehensive of yet more violent consequences

were the enthusiastic “Country” and Episcopalian and Catholic “Court” parties

in England to continue to inflame one another’s passions, friends of Locke’s

such as Charles II’s one-time Prime Minister, Shaftesbury, had gotten

involved in plots to prevent James’s succession. When those plots had failed and been

discovered Locke himself, as an associate of the plotters, had been forced

into exile in As far as Locke was concerned, all of these

civil upheavals had arisen from people’s absolute conviction of the

correctness of their opposed beliefs on matters of morals and revealed

religion, a conviction that had fostered a spirit of intolerance and

disputation that was eventually carried to arms. And, to reiterate, as far as Locke was

concerned, the philosophy of Descartes, with its uncritical attitude towards

the difference between understanding, belief, faith, and opinion, had done

more to invite than to remedy this circumstance. Locke took the proper antidote to intolerance

and disputation to rest with a careful examination of the powers of our

understanding. Knowledge, as far as Locke was concerned, arises when we make

judgments about the significance and implications of the information

available to us. For Locke, as for

Descartes, this information was presumed to take the form of “ideas” that are

apprehended by the understanding. Judgments assert the existence of relations between ideas, and

are made true or false by whether the ideas actually prove upon inspection to

exhibit the relations affirmed in the judgment. The limits of our knowledge are accordingly

coincident with what ideas we can actually apprehend, and what content those

ideas exhibit. What was needed, therefore, was an examination

of the origin and nature of our ideas.

If we could once agree on what ideas we truly possess, precisely

ascertain the content of those ideas, reject those that are perhaps not even

ideas at all, but merely unintelligible nonsense or meaningless words

masquerading as rational thought, determine what in general can be inferred

from these ideas, and determine what can and cannot be accepted on the basis

faith or revelation in the absence of a clearly apprehended relation between

ideas, then perhaps, Locke hoped, a way would be cleared for us to end our

disputations or at least develop a more tolerant attitude to opposed beliefs. This, accordingly, was the project Locke set

himself at the outset of the essay. As

he put it, it was to “enquire into the Original, Certainty, and Extent of

humane Knowledge; together, with the Grounds and Degrees of Belief, Opinion,

and Assent” (Essay I.i.2). But Locke immediately went on to propose to

undertake this enquiry in a startling way.

“I shall not at present meddle with the Physical Consideration of the

Mind,” he wrote, “or trouble my self to examine, wherein its Essence

consists, or by what Motions of our Spirits, or Alterations of our Bodies, we

come to have any Sensations by our Organs, or any Ideas in our

Understandings; and whether those Ideas do in their Foundation, any, or all

of them, depend on Matter or no.” How,

we might well wonder, could Locke propose to examine the origin and nature of

our ideas without considering how sensory stimulation affects the brain or

the extent to which ideas are the products of alterations in the matter of

the brain? For Hobbes this would have

been inconceivable and even Descartes, dualist though he was, was nonetheless

intensely concerned to determine how alterations in the body affect the mind

and what the ideas that are present in the mind tell us about our own body

and its material states. It bears noting that, unlike Hobbes and Descartes, Locke had been trained as a physician and

worked in that capacity for a part of his life. He would have attended anatomical lectures

and have had a very clear sense of the dim prospects the science of his day

held out for making any progress in uncovering how sensory stimulation

affects the brain or how the brain works within itself. Rather than attempt to gain knowledge of the

origin and nature of ideas by the method of observing what goes on in the

sense organs, nerves, and brain, Locke proposed a rather different method:

the “Historical, plain Method,” as he famously called it (I.i.2). The “Historical, plain Method” is the

method of first-person, introspective observation or reflective

self-consciousness. It begins with

meditations on one’s own ideas as they appear in consciousness and then seeks

to uncover the ways in which those ideas are worked up into knowledge claims

by means of introspectively evident processing operations — operations that

we may not always attend to, but that we can, with a bit of effort, reflect

upon and observe in action within ourselves.

As Locke put it, it involves considering “the discerning Faculties of

a Man, as they are employ’d about the Objects,

which they have to do with” (I.i.2).

It does not really matter, Locke claimed, what physical processes

first gave rise to our ideas. All that

matters is what ideas we have to start with and what we can proceed to do

with them once we have them. The “Historical, plain Method” was coincidentally

paralleled by the method employed by However, the project of investigating the

limits of knowledge and opinion by means of the “Historical, plain Method”

could only get off the ground if all of our knowledge turns out to be a

product of operations that lend themselves to study by the method, such as

operations of the understanding performed upon raw materials given to us in

sensory experience. Were it allowed

that there are some things that we are just born knowing, an investigation

into the bounds or limits of our cognitive powers would be pointless. There are no constraints on what we could

be born knowing. So, even if we did

discover that there are limits to what we can come to know later on, by

sensory experience and reasoning from sensory experience, it would remain

possible that those limits could be surpassed by what we were born knowing to

begin with. Opening the door to innate

knowledge opens the door to anyone wanting to claim that their most cherished

beliefs, however remote from what can be ascertained by experience or

reasoning from experience, are evidently and certainly true and known. It allows anyone who sees their most

cherished convictions challenged by a critique of the limits of our powers of

knowledge to challenge that result by claiming that we are all born knowing

these things, and that those who think otherwise are either willfully

perverse (denying what deep down they know to be true) or the victims of some

sort of birth defect that has left them incapable of knowing something perfectly

evident to the rest of us.

Alternatively, following a line of thought that was very popular in

the predestinarian Presbyterian and Puritan

denominations, it could be maintained that God has only elected a chosen few

for salvation and that these alone have been granted the gift of innate

knowledge. The rest, being corrupted

by original sin, not remedied by God’s Grace, will remain forever reprobate

and unknowing. Needless to say, views

such as these go hand in hand with a license to persecute those who do not

share your beliefs — at the very least to regard them as defective and

sub-human. As Locke himself dryly

commented, we should not be surprised to find that “enthusiasts,” those who

are convinced they have been granted knowledge that surpasses the powers of

understanding granted to the rest of us, are persecutors. Having done violence to the most noble part of themselves, by denying the sovereignty

of their understanding and preferring to love their convictions more than

what their understanding reveals to be the truth, it is not surprising that

they should not hesitate to do violence to others, and persecute those who do

not share their beliefs. Not surprisingly, therefore, Locke devoted a

good deal of effort to a preliminary attack on the supposition that there are

certain principles that we are just born knowing. In opposition to this view, he maintained

that all our ideas are obtained from sensory experience, and that all our

knowledge is obtained from discerning relations between ideas that have

previously been obtained from sensory experience, or from some mental

processing operation (such as compounding, dividing, abstracting or naming)

performed on ideas previously received from experience. On this supposition, there is a criterion

that we can appeal to in order to determine whether we do or do not have a

certain idea: we need merely trace the purported idea back to its roots in

sensory experience, identify the sorts of circumstances under which the root

parts of the idea are supposed to have arisen, put ourselves in those

circumstances, and see what idea we get in those circumstances. Whatever idea we get, that is all that the name for that idea can

possibly refer to. Then we need merely

determine what can be inferred from that content. This is so much the case that Locke quite

consistently applied the principle to himself. He observed that his own results in the Essay concerning human understanding

are subject to being in conformity with what his own readers could justly infer

from their own sensory experience. And

he claimed no more certain validity for them (Essay I.iv.25). This is quite opposed to Descartes’s

insistence that we must start from absolutely certain first principles, but

as Locke saw it, if reasoning from sense experience is not recognized as the

one, solid source of our knowledge, then there can be no limits to what can

be supposed to be known. Cromwell’s

mystical illuminations would be on a par with Descartes’s conviction that he

must exist as a thinking thing. However, the “Historical, plain Method” faces

a challenge of a different order — one that Locke acknowledged, but never

addressed and that consequently remains a persistent source of ambiguity and

frustration throughout the pages of the Essay. The method begins with introspective

identification of the information originally available for us to process into

knowledge claims: information that for Locke takes the form of a collection

of “ideas.” But it is very difficult

to say exactly what an idea is for Locke.

At I.i.8 he defined “idea” as “whatsoever is the Object of the

Understanding when a Man thinks” or “whatever it is which the Mind can be employ’d about in thinking.” But these are ambiguous phrases that might

be understood in at least three different ways. At least some of the objects we are

concerned with when thinking are naturally taken to be the objects that exist

outside of us in the surrounding world.

And, as odd as it may be to speak of an external object as if it were

an “idea” the mind is working with, Locke at least seems to have done so on

some occasions (II.viii.8). But when

he gave examples of ideas Locke included on his lists things like colours,

tastes, and smells — things which most of his early modern contemporaries had

since the time of Galileo considered to have no

existence outside of the body or the mind of the being that senses them. And, as a matter of fact, Locke was fond of

describing ideas in terms that suggest that they are mental images or

pictures of external things — images or pictures that may not resemble their

objects in all respects (II.i.25, II,viii.3, II.xi.17, III.iii.7,

IV.xi.1). However, on yet other

occasions, Locke described ideas in terms that suggest that they are not any

sort of object, either external or internal, but are rather actions or

operations. Locke maintained that we

have ideas of our own mental operations, such as perceiving, remembering,

willing, imagining, and understanding.

But the way we get these ideas is simply by “taking notice” of those

operations (II.i.4). The idea is not

an image or picture of the operation.

Neither is it that very image or operation. It seems rather to consist in the further

operation of “taking notice” of the fact that one is

perceiving, remembering, willing, etc.

Perceiving, remembering, willing, etc. are the objects we take notice

of, but the idea of these objects

seems to consist in the operation of taking notice of them. Did Locke mean to use the term “idea”

indifferently in all of these three senses, recognizing them each as a

distinct phenomenon that nonetheless deserves to be lumped in with the others

in a larger class? Or was his

considered view that one of the senses is primary and the others can be reduced

to it? The Essay does not say. Whatever difficulties there may be with

Locke’s project, its aim is one that merits a final comment. Locke was out to emancipate the individual

knower from the shackles of authority, just as many of his contemporaries were

out to emancipate the subject from the authority of the King. For Locke, republicanism was not just a

political doctrine, concerned with rights and powers within the state, but an

epistemological doctrine, concerned with the determination of truth. Locke’s own words put it best. And it was of no small advantage to

those who affected to be Masters and Teachers, to make this the Principle of Principles, That Principles must not

be questioned: For having once established this Tenet, That there are innate

Principles, it put their Followers upon a necessity of receiving some

Doctrines as such; which was to take [their followers] off from their own

Reason and Judgment, and put them upon believing and taking [these purported

principles] upon trust, without farther examination: In which posture of

blind Credulity, they might be more easily governed by, and made useful to

some sort of Men, who had the skill and office to principle [i.e., instruct]

and guide them. Nor is it a small

power it gives one Man over another, to have the Authority to be the Dictator

of Principles, and Teacher of unquestioned Truths; and to make a Man swallow

that for an innate Principle, which may serve to his purpose, who teacheth them. [Essay

I.iv.24] In contrast, Locke maintained that it is the

natural cognitive capacities of individuals exercised upon the things

themselves that are the best judges of truth, and he took this “republican”

epistemology so far as to hold that even expert opinion ought not to be

allowed to determine the views of individuals — though only on matters of

“probability” and at the cost of requiring that all individuals tolerate one

another’s contrary opinions on such matters. It was views such as these that made Locke’s Essay one of the most popular readings

among the founders of the American Revolution. QUESTIONS ON THE

1. What was the main

question that the Essay concerning human understanding was

written to answer?

2. What has so far served

as the main impediment to the advancement of knowledge?

3. In what does the

“Historical, plain Method” consist?

4. What are the main

consequences of a failure to inquire into the limits of what can be known by

our understanding?

5. What does the term,

“idea,” stand for?

6. What is the argument

from universal consent?

7. What, in general, is

wrong with the argument from universal consent?

8. What is wrong with

supposing that there might be certain truths that we have always known and

that were imprinted on our minds at birth, but that we are unconscious of?

9. Did Locke deny that we

have innate capacities? 10.

What is wrong with supposing that there might be certain

truths that we have always known and that were imprinted on our minds at

birth, but that we need to employ reason to discover what they are? 11.

What is wrong with supposing that there might be certain

truths that we have always known and that were imprinted on our minds at

birth, but that they only come into our consciousness when we attain the age

of reason? 12.

What is there about the fact that there are some truths

that we come to know very early in life that actually goes to prove that

these truths are not innately known? 13.

Did Locke believe that there are absolute truths

concerning what is right and wrong, or did he hold that moral rules are

purely conventional? 14.

What reasons did Locke offer for rejecting the view that

criminals still accept the truth of moral principles even though they do not

act in accord with them? 15.

Did Locke deny that we have innate dispositions and

tendencies? 16.

What are the main factors inducing people to take

principles upon trust? 17.

What special reason does a consideration of the “parts” of

principles give us for thinking that there could be no innate principles? 18.

What are the principal considerations leading Locke to

deny that ideas are innate? Note: Essay

I.iv.4-5. In this passage, Locke made a number of allusions to the ancient

Pythagorean doctrine of reincarnation, according to which our souls could be

born again, perhaps in the bodies of other kinds of animal. According to the classical historian of

philosophy, Diogenes Laertius, Pythagoras had

himself claimed to be the reincarnation of Euphorbus,

who was among those reported to have fought in the Trojan war. The reference to Pythagoras’s soul ending

up in the body of a cock may also be based on some historical source, though

I have as yet been unable to locate it.

The Pythagorean view that human souls are reincarnated in animal

bodies motivated many dietary restrictions but not, so far as the historical

record shows, one against fowl, so this may have been the matter for a joke

of some kind. Locke’s suggestion is

that even were the Pythagorean doctrine generally accepted, there would be

some who would hesitate to maintain that when the soul that previously

occupied the body of Pythagoras is reincarnated in the body of a cock, the

cock deserves to be considered to be “the same” as Pythagoras. He also notes that anyone who thinks these

speculations outlandish would have to confront similar problems when

considering the Christian doctrine of the resurrection. Would the resurrected soul still be the

same were it placed in a different body? 19.

What is Locke’s principal reason for denying that the idea

of God is innate? NOTES

ON THE Locke devoted most of Book I of the Essay to a protracted attack on the

belief that we have innate knowledge.

The attack is executed under three heads: I.ii

attacks the supposition that we have innate factual or “speculative”

knowledge (for example, knowledge that God exists and is no deceiver, that

the essence of body is extension, or that the mind is distinct from the

body); I.iii attacks the supposition that we have

innate practical or moral knowledge (for example, the knowledge that suicide

is immoral), and I.iv attacks the notion that we

have innate ideas (for example, the idea of an all perfect being or of the

ideas perfect geometrical shapes). Locke’s comments on the second of these topics

caused a great deal of consternation in certain circles of British

society. In his chapter on innate

practical principles Locke drew attention to the variation in ethical customs

that is evident to anyone who has “look’d abroad

beyond the Smoak of their own Chimneys” (I.iii.2),

and appealed to this evidence to undermine the claim that people are born

knowing certain ethical principles.

Locke was no relativist. He

believed that ethical propositions have an absolute foundation. But he also believed that this foundation

is not to be found in a little voice of conscience or an innate sense of the

natural law. It is rather to be found

in reasoning from the relations we are able to discern between our ideas —

reasoning that is no more innate than the reasoning that establishes any

other demonstration in geometry or logic or mathematics, but that is much

less evident and easy to obtain. The

wide variety of opinion in moral matters is not due to the fact that morals

are merely conventional, but rather to the fact that they are so difficult to

figure out. As a consequence, many

peoples and cultures have simply gotten them wrong. To many in Locke’s day, this looked like an

attempt to supplant an ethics based on the divinely revealed commandments

with a purely secular morality based on rational principles. The proposal was not one that endeared

Locke to partisans of either the puritanical or the “high” church forms of

Christianity in England, but it was one of a half dozen features that helped

earn his Essay concerning human

understanding the status of the bible of enlightened thought in Europe

(the others will be discussed in following chapters). Locke’s general attack on innate principles is

drawn from one basic argument. The

argument proceeds by first establishing a kind of reverse onus: it is

incumbent on those who believe in innate knowledge to prove there is such a

thing. After all, it is evident that

we do have senses and understanding and learn things from sensory experience

and from reasoning from sensory experience.

Anyone who wants to go beyond this, and postulate that in addition to

reasoning sensory experience we have some special, extra-sensory source of

knowledge, is first obliged to tell us why sensory experience and reasoning

from sensory experience are not alone adequate to give us all the knowledge

we have. Locke proceeded to observe that there has only

been one argument ever offered for innate knowledge: what we can call the

argument from universal consent. This

argument claims that there are some principles that all people in all times

and cultures have always known and agreed upon. These include speculative principles, such

as the principle of non-contradiction, and practical principles, such as the

principle that you ought to treat others as you would want them to treat

you. From the fact that there is

universal knowledge of and agreement to these principles, the argument goes

on to conclude that these principles must be innate or inborn in us all. Somewhat more formally laid out, the

nativist’s argument is as follows:

Locke charged that each of the premises of

this argument is false. The second premise is false because there is no principle

that is accepted by all people, at all times, and in all cultures. Even the principle of non-contradiction is

not such a principle, because it is not known by children and idiots. Neither are any other supposedly innate

principles. The first premise is false because, even were

we to grant its antecedent, its consequent could still be false. That is, even were we to grant that there

is some principle that everyone knows and agrees to, this could still be because

they learned it from sensory experience. For example, the principle that the

sky is blue is probably known even more generally than the principle of

non-contradiction, but no one would think that this is because it is innate

in us. It is rather because the

blueness of the sky is one of the first and most easily discovered items of

knowledge learned from sensory experiences. Having taken things this far, Locke proceeded

to turn the argument on its head.

While it does not follow that if a principle is universally assented

to, then it must be innate, it does follow that if there were any innate

principles then everyone would have to assent to them. The fact that children and idiots do not

assent to any principles therefore proves that none are innate.

A natural response to this counter-argument is

to attempt to dismiss the counterexample of children and idiots by claiming that

people can have an implicit knowledge of certain things that they do not

explicitly affirm. Being “innate” does

not (extravagantly) mean being assented to from the moment of birth. But Locke dismissed this with the charge

that nothing can be in the mind that it is not aware of. He had little more sympathy for a variant on

this response, according to which the fact that people assent to principles

as soon as they come to the use of reason proves that they must have been

implicitly known. The view is ambiguous,

he charged. Does it mean that when

people come to the use of reason, using their reason leads them to grasp and

assent these principles? In that case

the principles are confessedly not innate, but known only through deduction

and inference from something more fundamental (since that is just what reason

does: deduce unknowns from knowns by means of

argument and demonstration). Moreover,

the claim has the absurd consequence that it makes whatever is rationally

demonstrated into an innate truth. The

most abstract truths of mathematics — ones only recently discovered and

unknown to past generations are “innate” on this account because known

through reasoning. So might the view

instead just be that the age at which we come to be rational is the time when

these principles come to be known, even though it is not a process of

reasoning that discovers them? If so,

the claim is demonstrably false, since many people do not assent to these

principles when they come to the age of reason, but only do so much later, if

at all. Moreover, the claim is

extravagant, because it picks, as the cause of the recognition of innate

principles the point in time where we develop a capacity that, ex hypothesi,

has nothing to do with demonstrating or discovering these principles. Why pick on this faculty rather than any

other? If innate principles are not

known at the moment of birth, then the point in time when they emerge ought

to at least have something to do with the development of a capacity that

leads us to recognize them rather than one that confessedly has nothing to do

with this. Where moral principles are concerned, Locke

had the same points to make. Just as

the cases of children and idiots prove that there are no universally accepted

speculative principles, so the cases of those placed outside of the

constraints of laws and punishments (e.g., the members of an invading army

ransacking a town) or of people living in very different times and places,

prove that there are no universally accepted moral principles. If even thieves and villains observe

principles of justice and honesty within their own gangs, it is only because

they deduce that this is necessary if the gang is to hang together, not

because they have an innate knowledge of the truth of the principles. Such a knowledge

ought to make them reluctant to ever break the principles, not just to keep

them where their gang is concerned, as it ought to restrain the members of

invading armies, which it never does. As before it might be objected that thieves

and villains may still tacitly accept the principles of justice and honesty

even though they do not act on them.

But Locke insisted that failure to act on a principle is the best

indication that one does not really believe it, whatever one might say. Where some might object that thieves and

villains really know better and merely act differently out of weakness of the

will, being too strongly tempted by other considerations, Locke would respond

that what makes their will weak is that they can’t really bring themselves to

believe the moral principle, whatever they may say to the contrary. And, as a matter of fact, evil-doing

typically goes along with rationalizations offered to justify why the rule

deserves to be breached in this particular case, rather than an admission of

weakness of the will. It would be an

odd thing, Locke claimed, if some people were to accept the truth of a

practical principle and yet never act on it because it is of the very nature

of a practical principle that it is a principle governing action. Locke also had a few special remarks to make

about the weakness of the nativist position when applied to the case of

practical principles. He observed that

were moral principles truly innate, it would be absurd to ask for a

justification for them. Yet in fact

there is no moral principle that is so evident and so much beyond controversy

that people simply accept it and to not demand a justification. What is more, those moral principles that

seem most universally accepted, such as the principle that one ought to keep

one’s promises, are given different

justifications by different peoples, and this goes to prove that, even where

there might appear to be widespread agreement on a particular principle, it

is not because the principle is innate, but merely because a number of

different considerations all imply it. Locke claimed that all principles, even the

principle of non-contradiction, are actually learned from sensory

experience. As

noted earlier, Locke argued that all our knowledge arises from making

judgments about or, as he put it, discerning the relations among our

ideas. This means that knowledge

requires first obtaining ideas from sense experience, then comparing those ideas

with one another, and then describing the general results of those

comparisons. In the case of the

principle of non-contradiction, we first have to have an experience of more

than one idea. Then we need to compare

these two ideas with one another and discover that the one is not the other. This teaches us a kind of specific

principle of non-contradiction that applies just to the incompatibility

between those two ideas. We then need

to note a number of other instances of specific principles of

non-contradiction. At that point, we are put in a position to make an

induction from all of these specific principles to a general rule governing

them all: that everything is what it is and is not anything else. For example, the child suckles at its

mother’s breast and gets the idea of sweet, then tastes wormwood and gets the

idea of bitter. Reflection on these

ideas teaches it that sweet is not the same as bitter. Then it looks at one thing and gets the

idea of red, at another and gets the idea of white. Comparing all these

ideas, it observes that they are distinct — that sweet is not the same as

bitter or red or white, that red is not the same as white or sweet or bitter,

and so on. It then generalizes these

discoveries and others like them to formulate the principle that each idea is

what it is and no idea is ever what it is not. In effect, the general law of

non-contradiction arises by induction from experience in the same way as the

law of universal gravitation, and the former is no more necessary and no less

dependent on observation and induction than the latter. Since young children are likely incapable

of thought processes at this level of sophistication, it is no wonder that they show no evidence of understanding this

principle. According to Locke, what holds for the

principle of non-contradiction holds for all supposedly innate principles,

including the principles of mathematics and geometry. These principles are known only by first

obtaining, through sensory experience, ideas of particular shapes and numbers

of things, isolating the general features of those ideas, and then comparing

and contrasting the features so isolated and making judgments about the

relations of identity, similarity and difference, or equality and inequality

that those ideas are shown by experience to exhibit. People do not recognize these facts, Locke

observed, because they mistake principles learned very early in life for

principles they were born with, especially if those principles are broadly

accepted and frequently repeated in their society. To this fact we must add the consideration

that most people simply do not have the leisure to sit back and reflectively

examine their principles. The needs of

life compel them to make quick decisions, and lacking the opportunity for

reflection, they simply act on the basis of what they have been taught,

discover that it generally proves reliable, and so conclude that they are

best off if they simply accept the principles they have been taught. (As

Locke put it, they accept the principle that principles ought not to be questioned.) These are practices that can be further

entrenched by laziness, impatience, ignorance of the existence of widespread

exceptions (in those who have not looked beyond the smoke of their own

chimneys, as Locke put it), and indoctrination, all of which can dispose even

those with the leisure to reflect on their principles to refrain from doing

so. It is much easier to justify one’s

practices and beliefs by simply insisting that they are innate and beyond

question than to go to the hard labour of investigating the justice of them. There is a further factor that leads people to

suppose that moral principles are innate: conscience. When people consider violating moral

principles, particularly ones that they have been indoctrinated in since earliest

childhood, they sometimes feel a little voice of conscience advising them to

stop and do the right thing. This

leads them to suppose that conscience is a special moral cognitive capacity

that they were born with, that knows moral rules, and that tells those rules

to them. Locke dismissed this

reasoning, claiming that conscience is not knowledge of right or wrong, but

merely a feeling of pride or guilt about doing those things we have

previously been taught are right or wrong.

Someone who had been taught at her parent’s knee that loyalty to

family comes before loyalty to the law would feel the same twinge of

conscience about betraying a family member as someone who had been taught the

opposite would feel about breaking the law for the sake of a family member. After these devastating attacks on innate

theoretical and practical knowledge, Locke turned, in the final chapter of

the first part of the Essay, to

consider innate ideas. That this is

the topic that should come up last is in a way surprising, if only because

Locke is more often described as someone who denied that we have innate ideas

than as someone who denied that we have innate knowledge. But, in fact, he was far more invested in

the latter claim than in the former, and he was only interested in the latter

claim because he thought it would contribute to establishing the former. No knowledge is innate, Locke claimed,

because knowledge consists of asserting or denying relations between ideas,

and no ideas are innate. It is just as well that he shunted this

argument off into what is in effect an appendix to the first part of Essay, because this argument suffers

from the same defects he found in the opposed argument for innate knowledge

by appeal to universal consent: the premise that no ideas are innate is not

obviously true, and even if it were true, it does not imply that knowledge

could not be innate. Even if we need to have experience to supply

us with all of our ideas, it does not follow that we need further experience

to learn of all the relations between those ideas. The ideas, once given, might become the

subjects of relations that the mind itself is innately disposed to impose on

them. As Kant was later to claim, just

because all knowledge begins with experience, it does not follow that all knowledge

arises out of just what is supplied to us by experience. In order to make what William James was

later to call “the booming, bursting confusion” of all that is given to us in

sensory experience intelligible to ourselves, we

might need to bring this “matter” under forms or relations that are not

contained in experience. We might need

to draw distinctions between which of our experiences are experiences of

something new, that has just come into existence, and which are of something

old, that is only newly experienced by us but was in fact in existence all

along. Doing this might require

imposing a “objective” temporal, causal structure on

experience that is different from the actual temporal sequence of the

experiences and an “objective” spatial, part-whole structure on experience

that is again different from the part-whole structure of experience. In the process, we might need to invoke

concepts of cause and substance and principles of causality and identity that

have no clear origin in experience. But never mind whether or not knowledge could

be innate if ideas are not innate.

Locke’s argument depends on the truth of the antecedent,

that no ideas are innate, and his arguments on that score are

weak. He made his case by appeal to

the unlikelihood that children would form the highly abstract theoretical

ideas of possibility and identity that are involved in claims like the

principle of non-contradiction, the claim that it is impossible for the same

thing to both be and not be involve equally abstract concepts, like those of

identity, and had an easy time of it arguing that such ideas are not grasped

by children and so could not possibly be innate. But these are not the ideas he ought to

have been most concerned with. The

treatment of the ones he ought to have been most concerned with is something

of an embarrassment. For

I imagine any one will easily grant, That it would be impertinent to suppose,

the Ideas of Colours innate in a

Creature, to whom God hath given Sight, and a Power to receive them by the

Eyes from external Objects [Essay

I.ii.1] Locke cannot have meant this. He did not believe, any more than anyone

else did at the time, that colours exist outside of us in external objects

and are “received” from the eyes and the power of sight. Like all other early modern philosophers,

he believed that sensible qualities exist only in us, and not outside of us

in bodies. Admittedly, there is some

ambiguity in his use of terms. He is

capable of using the same word to refer to those qualities in bodies that

give them the power to produce ideas in us, and to refer to the ideas thus

produced. Nonetheless, as we will see

when we read Essay II.viii, he rather clearly and unambiguously maintained

that, when it comes to things like colour, understand that term how you will,

“There is nothing like our Ideas

existing in the Bodies themselves” (Essay

II.viii.15). If there is nothing like

the ideas existing in the bodies themselves, there is nothing

for the senses to “receive … from external objects” that is at like the ideas

produced in us when we are affected by those bodies. That leaves us having to confront the

consequence that we produce those ideas ourselves, out of our own inner

resources. We are innately

pre-disposed to form the ideas on the occasion of sensory stimulation. That having been said, Locke could still

maintain that sensory experience forms a necessary part of the antecedent

causal process leading us to produce our ideas of sensible qualities, and

that even though the ideas are produced by us and not conveyed into us from

the outside, we cannot produce them without having been first affected in the

right way by the right objects. Hume,

in a passage we will read later (Enquiry

II, note) was to comment that all Locke should have said is that we have no

power to imagine anything that is not compounded from simple elements

originally encountered in sensory experience, though Hume was himself capable

of equally ill-considered pronouncements (e.g., Enquiry 12.9 on the senses as “inlets” through which images are

“received”). It should be remarked in passing that though

Locke denied innate knowledge he did not deny either innate dispositions or

capacities, or innate tendencies of the will.

He was quite willing to admit that we are born with certain abilities

already developed in us, such as the ability to sneeze, the ability to make

judgments or the ability to learn.

(For obvious reasons, if we had to learn how to learn, we would be in

deep trouble.) Indeed, Locke was

willing to grant that we are born with all our cognitive capacities intact

and ready to work. But to be born with

the ability to learn or to make judgments is not at all the same thing as to

be born with a particular judgment already learned and in your head. The capacity may be innate, but for Locke

nothing emerges from that capacity until it is applied to sensory

experience. There can therefore be no

innate products of cognitive processes, even though there can be innate

cognitive capacities. Similarly, Locke was willing to admit that we

might be born with innate impulses or tendencies of will. We might be born, for instance, with an

innate tendency to curl our toes when the sole of the foot is stroked, or an

innate tendency to crawl back from a precipice, or an innate tendency to

pursue pleasure and avoid pain, that is, to act out of self-interest. But a tendency to motion is not a

belief. You do not curl your toes when

your sole is stroked because you believe anything. The sensory stimulus

simply elicits that motor response.

Similarly, the infant need not shrink back from a precipice because it

believes it will fall over the edge, or pursue pleasure and avoid pain

because it believes that pleasure is good for it, but simply because the

visual or tangible stimulus elicits that response. ESSAY

QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Locke’s definition of

“idea” as “whatever it is, which the Mind can be employ’d

about in thinking,” (Essay I.i.8)

has long puzzled commentators. According

to one theory, Locke expressed himself so vaguely because he wanted to

include both images formed by the imagination and concepts grasped by the

intellect under the umbrella of the term, “idea.” However, other commentators have criticized

Locke’s definition for failing to provide adequate guidance on the question

of whether ideas are acts whereby the mind thinks of an object or “third

things” (in addition to the mind and the objects in the external world) that

are produced in the mind as a consequence of the activity of objects. These questions have recently been

judiciously reviewed by Michael Ayers, Locke,

2 vols. (London: Rougledge, 1991), vol. 1, chs. 5-7. Summarize and comment on Ayers’s

position.

2. The main objection

that Locke raised against innate knowledge in Essay I.ii-iii is that no good argument

has been offered for supposing that there is any such thing. However, Locke only ever considered one

argument for innate knowledge: the argument from universal consent, and it

might be objected that this is to attack a straw man, for there are better

and more convincing arguments for innate knowledge. Locke was attacked in just this way by

Leibniz, who wrote an extended commentary on Locke’s Essay, the New essays on human understanding. Leibniz’s New essays have been translated by Peter Remnant and Jonathan

Bennett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981). Review Book I of Leibniz’s New essays (which comments on Book I of

Locke’s Essay) and write a paper

outlining Leibniz’s main objections to Locke.

Assess whether Leibniz or Locke has the better case. |