|

19 Locke, Essay Epistle and I.i.1-4,6-8;

II.i.1-8,20,23-25; ii, viii.1-6, iii-vi; vii.1-2,7-10 Sensation

–

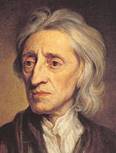

Locke, Essay I.iv.25 Though John Locke’s Essay concerning human understanding appeared three years after However, another, much more significant

factor behind the positive reception of Locke’s work was its agreement with

the increasingly republican and anti-authoritarian political views of the

day. Unlike Descartes, Locke was not

primarily motivated to write his book on human understanding in order to

provide a justification for a certain kind of philosophy of nature. Instead, he was motivated by social,

religious, and political concerns. The

introductory Epistle to the Essay

contains a famous allusion to these concerns.

Were

it fit to trouble thee with the History of this Essay, I should tell thee,

that five or six Friends, meeting at my Chamber, and discoursing on a Subject

very remote from this, found themselves quickly at a stand, by the

Difficulties that rose on every side.

After we had a while puzzled our selves, without coming any nearer a

Resolution of those Doubts which perplexed us, it came into my Thoughts, that

we took a wrong course; and that, before we set our selves upon Enquiries of

that Nature, it was necessary to examine our own Abilities, and see, what

Objects our Understandings were, or were not fitted to deal with. [Epistle, Nidditch 7, Winkler 1-2] James Tyrell, one of the “friends”

present at this famous meeting, later reported that the subject of discussion

had not been any topic in natural philosophy, but rather the principles of

morality and revealed religion. It was

the foundations of our knowledge of these topics that Locke was most concerned

to investigate. And Locke made no

secret of the conclusions he hoped to draw from that investigation. Rather than establish a particular doctrine

beyond any hope of contestation, Locke hoped that, by clearly drawing the

bounds between what it is actually possible to know and what can only be

entertained as a matter of opinion he would, “prevail with the busy Mind of

Man, to be more cautious in meddling with things exceeding its Comprehension;

to stop, when it is at the utmost Extent of its Tether; and to sit down in a

quiet Ignorance of those Things, which, upon Examination, are found to be

beyond the reach of our Capacities,” avoiding “Disputes about Things, to

which our Understandings are not suited” in favour of a general toleration of

the contrary opinions of others (I.i.4). For Locke, doing this was not tantamount

to arguing for scepticism or discounting the efficacy of all of our knowing

powers. He considered that there are

things that we can know, many of them concerning the moral matters of most

concern to us. By drawing the boundaries

between what can be known and what cannot he hoped to avoid the sceptical

funk that people often fall into when, having carried their researches beyond

anything they can hope to achieve and gotten nowhere, they turn in disgust to

the contrary opinion that nothing at all can be known. But he also hoped to prevent people from

disputing about things that we cannot hope to know for sure to be true and

mount a powerful argument for toleration of the contrary opinions of others

in cases where knowledge is beyond our reach and the best we can manage is to

form opinions. The general project of examining what

things our understandings are and are not capable of coming to know is one

that Locke found to be hindered, rather than helped, by the philosophy of Descartes. Despite his avowedly great concern to

proceed from absolutely certain first principles, and not accept anything

that he could not clearly and distinctly perceive to be true, Descartes was

not very reflective about his own understanding or about the other operations

of his mind, such as imagining, willing, judging, and believing. As has been noted in past chapters,

Descartes never really paused to consider how he could tell a clear and

distinct perception on the part of the understanding apart from a natural

instinct, or either apart from a hasty judgment. He had more or less simply helped himself

to these notions, as if they were patently evident. As far as Locke was concerned, this was

tantamount to an open invitation to others to do the same, and base their

most fondly cherished beliefs not on reasoning or evidence, but the bald

affirmation that these beliefs are patently evident to the understanding,

innately known, or divinely inspired through a special gift of Grace,

illuminating the understanding with a power it could not resist.

The natural concomitant of “enthusiastic”

religious practices was a belief in the priesthood of all believers (or at

least, those among them — the “Saints” — who had been elected for salvation

and chosen by God to receive his Grace).

These practices and beliefs were inimical to all forms of authority,

be they ecclesiastical, civil, or military.

The Tudor and Stuart monarchs in Apprehensive of yet more violent

consequences were the enthusiastic “Country” and Episcopalian and Catholic

“Court” parties in England to continue to inflame one another’s passions,

friends of Locke’s such as Charles II’s one-time Prime Minister, Shaftesbury,

had gotten involved in plots to prevent James’s succession. When those plots had failed and been

discovered Locke himself, as an associate of the plotters, had been forced into

exile in As far as Locke was concerned, all of

these civil upheavals had arisen from people’s absolute conviction of the

correctness of their opposed beliefs on matters of morals and revealed

religion, a conviction that had fostered a spirit of intolerance and

disputation that was eventually carried to arms. And, to reiterate, as far as Locke was

concerned, the philosophy of Descartes, with its uncritical attitude towards

the difference between understanding, belief, faith, and opinion, had done

more to invite than to remedy this circumstance. Locke took the proper antidote to

intolerance and disputation to rest with a careful examination of the powers

of our understanding. Knowledge, as far as Locke was concerned, arises when

we make judgments about the significance and implications of the information

available to us. For Locke, as for Descartes,

this information was presumed to take the form of “ideas” that are

apprehended by the understanding. Judgments assert the existence of relations between ideas, and

are made true or false by whether the ideas actually prove upon inspection to

exhibit the relations affirmed in the judgment. The limits of our knowledge are accordingly

coincident with what ideas we can actually apprehend, and what content those

ideas exhibit. What was needed, therefore, was an

examination of the origin and nature of our ideas. If we could once agree on what ideas we

truly possess, precisely ascertain the content of those ideas, reject those

that are perhaps not even ideas at all, but merely unintelligible nonsense or

meaningless words masquerading as rational thought, determine what in general

can be inferred from these ideas, and determine what can and cannot be

accepted on the basis faith or revelation in the absence of a clearly

apprehended relation between ideas, then perhaps, Locke hoped, a way would be

cleared for us to end our disputations or at least develop a more tolerant

attitude to opposed beliefs. This, accordingly, was the project Locke

set himself at the outset of the essay.

As he put it, it was to “enquire into the Original, Certainty, and

Extent of humane Knowledge; together, with the Grounds and Degrees of Belief,

Opinion, and Assent” (Essay

I.i.2). But Locke immediately went on

to propose to undertake this enquiry in a startling way. “I shall not at present meddle with the

Physical Consideration of the Mind,” he wrote, “or trouble my self to

examine, wherein its Essence consists, or by what Motions of our Spirits, or

Alterations of our Bodies, we come to have any Sensations by our Organs, or

any Ideas in our Understandings; and whether those Ideas do in their

Foundation, any, or all of them, depend on Matter or no.” How, we might well wonder, could Locke

propose to examine the origin and nature of our ideas without considering how

sensory stimulation affects the brain or the extent to which ideas are the

products of alterations in the matter of the brain? For Hobbes this would have been

inconceivable and even Descartes, dualist though he was, was nonetheless

intensely concerned to determine how alterations in the body affect the mind

and what the ideas that are present in the mind tell us about our own body

and its material states. It bears noting that, unlike Hobbes and

Descartes, Locke had been trained as a physician and worked in that capacity

for a part of his life. He would have

attended anatomical lectures and have had a very clear sense of the dim

prospects the science of his day held out for making any progress in

uncovering how sensory stimulation affects the brain or how the brain works

within itself. Rather than attempt to gain knowledge of

the origin and nature of ideas by the method of observing what goes on in the

sense organs, nerves, and brain, Locke proposed a rather different method:

the “Historical, plain Method,” as he famously called it (I.i.2). The “Historical, plain Method” is the method

of first-person, introspective observation or reflective

self-consciousness. It begins with

meditations on one’s own ideas as they appear in consciousness and then seeks

to uncover the ways in which those ideas are worked up into knowledge claims

by means of introspectively evident processing operations — operations that

we may not always attend to, but that we can, with a bit of effort, reflect

upon and observe in action within ourselves.

As Locke put it, it involves considering “the discerning Faculties of

a Man, as they are employ’d about the Objects,

which they have to do with” (I.i.2).

It does not really matter, Locke claimed, what physical processes

first gave rise to our ideas. All that

matters is what ideas we have to start with and what we can proceed to do

with them once we have them. The “Historical, plain Method” was

coincidentally paralleled by the method employed by However, the “Historical, plain Method”

faces a challenge —

one that Locke acknowledged, but never addressed and that

consequently remains a persistent source of ambiguity and frustration

throughout the pages of the Essay. The method begins with introspective

identification of the information originally available for us to process into

knowledge claims: information that for Locke takes the form of a collection

of “ideas.” But it is very difficult

to say exactly what an idea is for Locke.

At I.i.8 he defined “idea” as “whatsoever is the Object of the

Understanding when a Man thinks” or “whatever it is which the Mind can be employ’d about in thinking.” But these are ambiguous phrases that might

be understood in at least three different ways. At least some of the objects we are

concerned with when thinking are naturally taken to be the objects that exist

outside of us in the surrounding world.

And, as odd as it may be to speak of the external object as if it were

an “idea” the mind is working with, Locke at least seems to have done so on

some occasions (II.viii.8). But when

he gave examples of ideas Locke included on his lists things like colours,

tastes, and smells — things which most of his early modern contemporaries had

since the time of Galileo considered to have no existence outside of the body

or the mind of the being that senses them.

And, as a matter of fact, Locke was fond of describing ideas in terms

that suggest that they are mental images or pictures of external things —

images or pictures that may not resemble their objects in all respects

(II.i.25, II,viii.3, II.xi.17, III.iii.7, IV.xi.1). However, on yet other occasions, Locke described

ideas in terms that suggest that they are not any sort of object, either

external or internal, but are rather actions or operations. Locke maintained that we have ideas of our

own mental operations, such as perceiving, remembering, willing, imagining,

and understanding. But the way we get

these ideas is simply by “taking notice” of those operations (II.i.4). The idea is not an image or picture of the

operation. Neither is it that very

image or operation. It seems rather to

consist in the further operation of “taking notice” of the fact that one is

perceiving, remembering, willing, etc.

Perceiving, remembering, willing, etc. are the objects we take notice

of, but the idea of these objects

seems to consist in the operation of taking notice of them. Did Locke mean to use the term “idea”

indifferently in all of these three senses, recognizing them each as a

distinct phenomenon that nonetheless deserves to be lumped in with the others

in a larger class? Or was his

considered view that one of the senses is primary and the others can be

reduced to it? The Essay does not say. Whatever difficulties there may be with

Locke’s project, its aim is one that merits a final comment. Locke was out to emancipate the individual

knower from the shackles of authority, just as many of his contemporaries

were out to emancipate the subject from the authority of the King. For Locke, republicanism was not just a

political doctrine, concerned with rights and powers within the state, but an

epistemological doctrine, concerned with the determination of truth. Locke’s own words put it best. And it was of no small advantage

to those who affected to be Masters and Teachers, to make this the Principle

of Principles, That Principles must

not be questioned: For having once established this Tenet, That there are

innate Principles, it put their Followers upon a necessity of receiving some

Doctrines as such; which was to take [their followers] off from their own

Reason and Judgment, and put them upon believing and taking [these purported

principles] upon trust, without farther examination: In which posture of

blind Credulity, they might be more easily governed by, and made useful to

some sort of Men, who had the skill and office to principle [i.e., instruct]

and guide them. Nor is it a small

power it gives one Man over another, to have the Authority to be the Dictator

of Principles, and Teacher of unquestioned Truths; and to make a Man swallow

that for an innate Principle, which may serve to his purpose, who teacheth them. [Essay

I.iv.24] In contrast, Locke maintained that it is

the natural cognitive capacities of individuals exercised upon the things

themselves that are the best judges of truth, and he took this “republican”

epistemology so far as to hold that even expert opinion ought not to be

allowed to determine the views of individuals — though only on matters of

“probability” and at the cost of requiring that all individuals tolerate one

another’s contrary opinions on such matters. It was views such as these that made

Locke’s Essay one of the most

popular readings among the founders of the American Revolution. QUESTIONS

ON THE

1. What was the

main question that the Essay concerning human understanding was

written to answer?

2. What has so far

served as the main impediment to the advancement of knowledge?

3. In what does the

“Historical, plain Method” consist?

4. What are the

main consequences of a failure to inquire into the limits of what can be

known by our understanding?

5. What does the

term, “idea,” stand for?

6. What are the two

sources of ideas?

7. What exactly is

conveyed to our minds by our senses?

8. What are the

“originals” from which our ideas “take their beginnings?”

9. What evidence

did Locke offer for supposing that all ideas originate from either sensation

or reflection? 10.

Do we only ever experience one simple idea at a

time? 11.

What makes simple ideas simple? 12.

Is it possible for us to spontaneously create ideas

on our own? 13.

Do we have ideas of privations? 14.

What did Locke consider to be the likely causes of

our ideas of white and black? 15.

Did Locke think it is even likely that any of our

ideas could be caused by privations? 16.

What is solidity and how does it differ from

hardness? 17.

Why does the mind consider solidity to be a feature

even of bodies that are too small to see? 18.

What does it mean for a body to fill a space? 19.

How does the extension of body differ from that of

space? NOTES

ON THE In Book II of the Essay Locke turned to his proper project: the anatomy of our

knowing powers. There are three parts

to this project. First, Locke tried to

determine what information is available to our knowing powers to work with,

or, as he preferred to put it, what sorts of ideas are given to the

mind. Then he tried to determine what

sorts of things we can and cannot come to know on the basis of this

information. Finally, he inquired into

what things we can accept on faith or trust, even though they may be beyond

our knowledge. The first of these tasks, the survey of the information available

to the understanding to work with, is undertaken over Book II of the Essay. Over the course of this book,

Locke identified the main sources from which we originally receive

information or ideas, and what sorts of ideas we receive from these

sources. He then identified various

operations that the mind is capable of performing on originally received

ideas and identified various derivative ideas that result from these

operations. Over Essay II.i-viii he took on just the

first of these tasks: identifying the main sources from which we originally

receive ideas and what sorts of ideas we receive from these sources. For Locke, there are three sources of

ideas: sensation, reflection, and imagination. However, imagination is not an original

source of ideas. It generates new

ideas only by repeating, compounding, dividing, comparing, abstracting, and

naming previously obtained ideas. So

there are just two ultimate sources of ideas, sensation and reflection. Sensation. Sensation is the most basic of these

remaining two ways, but also the most difficult to understand properly. In general, Locke thought that the ideas

that arise from sensation are those we get when we observe external objects

(II.i.2). But it is important to be

clear about just what this means. For

Locke, the observation of external objects is not something that we do; it is

rather something that is done to us.

We are passive when receiving ideas by sensation (II.i.25). For observation to take place, objects must

first affect our sense organs. The

effects that objects have on our sense organs are then conveyed to the brain,

which Locke described as the mind’s “presence room” (II.iii.1). (A presence room was a room where a person

went in order to have an audience with the Sovereign.) Once there, the effects somehow cause the

mind to have or become aware of an idea.

As Locke wrote at II.i.3: when I say the senses convey [ideas]

into the mind, I mean, they from external Objects convey into the mind what

produces there those Perceptions. The

claim remains frustratingly ambiguous.

Is “perceptions” used as a synonym for “ideas,” in which case the

claim would be that what is conveyed into the mind is something that causes

ideas to arise in the mind? Or are

ideas the things that are perceived, so that what is conveyed into the mind

is something that produces a perception of something else, called an

idea? And is anything literally

conveyed into the mind or is it

just the case that the occurrence of certain brain states is somehow

connected with the emergence of perceptions in the mind? At II.23 Locke defined sensation as

“such an Impression or Motion, made in some part of the Body, as produces

some Perception in the Understanding.”

This suggests that what is conveyed is not conveyed into the mind but only into the brain (the mind’s “presence

room”). Somehow, this conveyance has

an effect on the mind, giving rise to an idea (perception) or the perception

of an idea. According to II.23,

sensations are motions of body parts, not ideas. Ideas are things perceived by the

understanding. Importantly, and far from

trivially, Locke seems to have thought that the perceptions produced in the

understanding are not perceptions of the very things that cause those

perceptions — of the motions produced in our body parts. At Essay

II.viii.4 Locke wrote, at least speculatively, that “all Sensation” is

“produced in us, only by different degrees and modes of Motion in our animal

Spirits, variously agitated by external Objects,” so that “the abatement of

any former motion, must as necessarily produce a new sensation, as the

variation or increase of it; and so introduce a new Idea.” But the ideas thus

introduced are not ideas of motions of animal spirits. They are, according to II.iii.1, “Light and

Colours, as white, red, yellow, blue; with their several Degrees or Shades, and

Mixtures, as Green, Scarlet, Purple, Sea-green, and the rest … All kinds of

Noises, Sounds, and Tones … The several Tastes and Smells” as well as “Heat

and Cold, and Solidity.” On this

account, sensations are not ideas; sensations are physiological states of the

sensory nerves and brain that cause the mind to have certain ideas — those

ideas that we denominate as ideas “of” (i.e., ideas coming from) sensation. And just as the perceptions produced in

the understanding do not resemble the sensations or body motions that cause

them, so they do not — at least not obviously or necessarily — resemble

anything in the external objects that affect the sense organs. Essay

II.viii.2 is once again explicit: These are two very different

things, and carefully to be distinguished; it being one thing to perceive,

and know the Idea of White or

Black, and quite another to examine what kind of particles they must be, and

how ranged in the Superficies, to make any Object appear White or Black. So the properties of white and black

that we perceive as a consequence of sensation cannot be confidently affirmed

to resemble anything that exists in the outside world, at least as far as

Locke was willing to say at this point.

External objects exist in the outside world. The ideas we receive through sensation do

not even exist in our bodies or brains.

Physiological states of the sensory nerves and brain exist in our

bodies and brains. Our sense organs

and brains convey something from external objects to the mind. This conveyed item is not our ideas of

colours, heat and cold, or other qualities.

What is conveyed by the senses is rather some motion or impression. This motion or impression somehow produces

ideas of colours, heat and cold, and other qualities in the mind. So, whatever ideas may be, they are

something that arises in the mind.

They are not something that is conveyed into the mind from the

outside. They are, however, caused to

arise in the mind by something conveyed to the brain from the outside. Consequently, the extent to which there is

any resemblance between ideas and objects, or, for that matter, between ideas

and their causes in the brain, is unclear.

Locke considered this matter later, in II.viii.7-26, the topic for the

next lecture. This is not to say that Locke had a

single, clear and settled account to give of sensation. As will be seen to have been very often the

case, he was often not consistent in his views, either on this or other

important matters, and was capable of speaking in ways that convey an

entirely different picture. Consider

once again Essay II.iii.1: Thus Light and Colours, as white,

red, yellow, blue; with their several Degrees or Shades, and Mixtures, as

Green, Scarlet, Purple, Sea-green, and the rest, come in only by the

Eyes: All kinds of Noises, Sounds, and

Tones only by the Ears: The several

Tastes and Smells, by the Nose and Palate.

And if these Organs, or the Nerves, which are the Conduits, to convey

them from without to their Audience in the Brain, the mind’s Presence-room

(as I may so call it), are any of them so disordered, as not to perform their

Functions, they have no Postern to be admitted by … In this extraordinary passage, light,

colours, and the other sensible qualities are described as things that do

exist outside us and as things that are conveyed by the nerves from outside

of us into the brain, in contradiction to what must in fact be Locke’s

considered view of things. Texts that

will be examined in conjunction with the next lecture make it clear that he

could not have meant this literally.

It must be treated as a metaphorical description — one that is

particularly unfortunate for not being labeled as such and for therefore

being liable to misinterpretation. We

need to beware of this. Locke was a

sloppy writer. Just because he says

one thing in one place, it does not follow that he really meant it. We need to be sure that he did not say

something inconsistent with it somewhere else. If he did, we cannot jump to the conclusion

that he contradicted himself but must sympathetically consider things in

light of the entire corpus of his thought to try and sift out whether one or

the other pronouncement was not intended to be taken literally and what he

was ultimately trying to get at. To return to the topic, though on

Locke’s considered view ideas arise only in the mind, and are not conveyed

into it from outside, it does not follow that ideas are innate. They are not innate because they only get

produced in the mind through something else being, as Locke put it, conveyed

to the brain by the senses from objects.

Somehow — we do not know how — objects affecting the senses and so the

brain determine what ideas are produced in the mind, so that, were those

objects not to affect the senses and the brain, the ideas would simply not

arise. The mind is nonetheless so

constituted as to produce certain ideas when appropriately stimulated, and

this constitution is innate. Locke had

no quarrel with innate abilities and innate dispositions; though he did

reject ideas and judgments that are supposed to emerge out of the

constitution of the mind independently of any influence from the senses. Reflection. Locke is famous for having denied that

we have innate knowledge or innate ideas, a topic to which the first book of

the essay is largely devoted. But he

accepted that we have innate abilities, such as the ability to perceive,

remember and imagine. Some of our

innate abilities are cognitive and some conative in nature. The conative abilities produce desires and

aversions and our other passions, and the cognitive abilities modify our

ideas in various ways: by comparing them and noting marks of resemblance or

difference, by compounding or dividing them, by abstracting their common

characteristics, by applying names to them, or simply by attending to them

and leading us to become conscious of their presence. Once the mind acquires a store of ideas

from sensation, these abilities begin to operate on the ideas. Locke supposed that the mind’s

operations are transparent to it. It

need only exercise an adequate degree of attention in order to become aware

that it is performing them. This means

coming to have an idea of the particular operation it is performing. These ideas are ideas of reflection. It is important to stress that though

the operations the mind performs may be operations it is innately enabled to

perform, the ideas it forms of these operations are not innate but only

discovered by experience. This is because,

unless something first happens to the mind to arouse it to perform the innate

operations, it will never become aware of what abilities it has. The mind’s abilities only become

transparent to it through their exercise, and this requires that sensations

first come into it and create the occasion for it to exercise its abilities. Moreover, it requires that the

individual attend to what they are doing — which is something that they need

not necessarily do. Locke remarked

that many people live large parts of their lives without ever attending to

their own mental operations, and so without forming distinct ideas of them,

even though they perform them (II.i.7-8).

This is different from how things are with ideas of sensation. Whereas we are largely passive in the

reception of the latter, obtaining the former requires some action on our

part. We need to focus our attention

in a way that is not generally required for ideas of sensation. A further difference between ideas of

sensation and ideas of reflection goes unremarked. It has already been noted that when

discussing ideas of sensation Locke stressed that the idea produced by the

sensation is one thing, its cause is something else, and knowledge of the one

implies nothing about the other. Thus,

“A Painter or Dyer, who never enquired into their causes, hath the Ideas of White and Black, and other

Colours, as clearly, perfectly, and distinctly in his Understanding, and

perhaps more distinctly, than the Philosopher, who hath busied himself in

considering their Natures [i.e., the features of bodies that cause our ideas

of colours].” But it appears that, in

having ideas of perceiving, willing, remembering, discerning, desiring,

fearing, judging, reasoning, knowing, and so on, we are having ideas of those

very operations and not of something distinct from them. Having these ideas of reflection does not

involve having an “image” produced in us by causes that may in no way

resemble that image (to follow the comparison of ideas with images in a

mirror of II.i.25). It instead

consists of simply “taking notice” of the very operation itself that the mind

is performing. The mind does not “take

notice” of the very motions in the body parts that cause ideas of perception,

much less of the qualities in objects that are ultimately responsible for

producing those motions. But its ideas

of reflection are defined as “that notice which the Mind takes of its own

Operations, and the manner of them, by reason whereof, there come to be Ideas of these operations in the

Understanding” (II.i.4). Locke never

commented on this difference between ideas of sensation and ideas of

reflection. Indeed, he seems not to

have noticed it. Locke’s discussion of ideas of

reflection has anti-Cartesian implications that he remarked on over

II.i.9-19. For Locke, the mind is not

equated with the act of thinking. It

is rather described as the thing that holds ideas. It is in principle possible that the mind

could be empty of ideas (as the metaphor of blank paper at II.i.2 implies),

yet still exist. Thought, therefore,

is not the essence of the mind, as Descartes supposed, and it is not

necessary that the mind always think. Locke attempted to prove this

empirically, by claiming that there is no thought in deep sleep, even though

the mind may be supposed to persist throughout. Locke’s

Empirism. Locke claimed

that the two sources of sensation and reflection are the sole sources of our

ideas. Ideas that do not originate

from sensation or reflection are generated by acts of mind performed upon

ideas that have previously been received from sensation or reflection. However, this is not something Locke

claimed to prove with certainty. The

Cartesian idea of starting from absolutely certain first principles is one

that he rejected. But while he did not

have a proof from first principles, he did think we have good evidence for

this proposition. The evidence is of

two main sorts. Locke first claimed that there are

certain ideas that are obviously acquired from sensation. He then tried to show how all of our other

ideas could be derived from those that are obviously acquired from sensation. The second of these points is one that

Locke argued for over the course of Essay

II. To buttress his position on the

first point, the claim that there are certain ideas that are obviously

acquired from sensation, Locke appealed to our observation of children

(II.i.6 and 22), of those born lacking the use of particular sense organs

(II.ii.3, II.iii.1, and III.iv.11), and of those who have never had

experience of certain objects (II.i.6-7 and ii.2). Observation appears to indicate that there

are certain ideas that children only acquire from experience; indeed, some of

these ideas are acquired so late that we can actually remember the occasion

when we first acquired them (think of the tastes of certain wines or exotic

foods). Even more tellingly, those who

were born without the use of a particular sense organ cannot form any ideas

of the qualities specific to that sense.

Those who have been blind since birth, for example, are unable to form

any idea of colours, and even extensive discussion with those who can see is

inadequate to give them any concept of what the experience of colours is

like. A similar point holds for those who, while they have the use of all

their senses, have never had their senses affected by particular

objects. Those who have never tasted

pineapple, for example, are no more able to form a concept of this taste than

someone who has been blind since birth is able to form an idea of colour. Locke took these points to indicate that

there are certain ideas that can only be obtained through having particular

sense organs affected by particular objects, and that can in no way arise in

the absence of those objects or in the absence of the appropriate sense organs. Having established that much, it only

remained for him to argue that all of our remaining ideas are derived from

one or another set of operations performed upon these obviously acquired

ideas. Simple

and complex ideas. The ideas we get

from external sensation and reflection may be either simple or complex. They are simple when they “exhibit one

uniform appearance” (II.ii.1), that is, when they do not look to contain more

than one thing. They are complex when

they are repeated, compounded or otherwise related to one another. Examples of simple ideas are all the

individual colours in their different tints, tones, and shades; particular

smells and tastes like the smell of lily or rose and the taste of sugar;

noises, sounds and tones; feelings of hardness and softness, warmth and

coldness, smoothness and roughness, and solidity; also the ideas we have of

space or extension in general, duration in general, motion in general; and

the ideas we have of the distinct acts of the mind: believing, imagining, remembering,

willing, and so on. Complex ideas can arise from modifying

simple ideas by repeating, compounding, dividing, delimiting or comparing

them. For example, the ideas of shapes

arise from delimiting simple ideas of space, the ideas of numbers from repeating

simple ideas of numbers; the ideas of a red triangle or a turtle from

compounding simple ideas or modifications of simple ideas, and the ideas of

brightness or cause by comparing ideas. Locke remarked that our “understanding”

(i.e., imagination) can itself spontaneously repeat, compound, divide or

compare ideas to create new complex ideas, and he also claimed that our ideas

“enter by the Senses simple and unmixed” (II.ii.1). But it would be a mistake to suppose that

for Locke we receive simple ideas one after another in a stream, and that all

aggregation of ideas is due to the mind.

On the contrary, in the sentence immediately following that in which

he wrote that ideas enter by the senses simple and unmixed he stated that

“the Sight and Touch often take in from the same Object, at the same time,

different Ideas.” It would appear, therefore, that Locke

considered us to receive entire bundles or collections of ideas

simultaneously through the act of perception.

He just thought that these ideas retain their individuality so that

they can be immediately told apart from one another. Simple ideas cannot be confused with one

another (so they are perfectly clear) and, being simple, they have no parts

(so there is nothing in them that can be confused with anything else). The awareness of simple ideas therefore

constitutes the clearest and most distinct knowledge that we are capable

of. “Nothing can be plainer,” Locke

wrote, “than the clear and distinct Perception [we have] of those simple

Ideas” (II.ii.1). Over II.viii.1-6 Locke remarked on an

anti-Cartesian implication of his account of simple ideas: On his account, ideas of privative

qualities like those of black, cold, or soft, are as real and positive as any

others. There is, in other words, no

such thing as material falsity.

(Material falsity was discussed in conjunction with Descartes’s

arguments in the 3rd Meditation and at the close of the first part

of his Principles.) For Descartes, the only “simple ideas”

that are perceived with perfect clarity and distinctness are those the

understanding is supposed to be able to discern through its own inner

resources, without the aid of the senses.

Locke’s rejection of understanding as a distinct source of ideas led

him to invert Descartes’s picture. For

Locke, what is most certain and trustworthy is what our senses first tell us

about. This includes the modes of

thought (which are revealed to us by reflection) and the modes of extension

(which are revealed to us by sensation), but also all the other sensible

qualities — colours, weight, solidity, temperature, scent, and the like. The “historical, plain method” is not

concerned with uncovering what may be in the object that causes these ideas —

whether the presence of a thing or its absence — but with investigating how

that idea gets processed once it has been received. From this perspective,

even if there were “materially false” ideas produced in us by nothing at all,

they would have as real and positive a role to play as any other ideas. The idea itself is not nothing, even if its

cause might be. But Locke also had problems with the

notion that our supposedly privative ideas could in fact be caused by

nothing. If one idea (for example

heat) is caused by a certain motion in the sense organs (say high and

frequent vibration), then the opposite of that idea (cold) would be brought

about by the absence of that motion (no vibration) or by a contrary

motion. But the absence of motion is

not nothing, but rest, and a contrary motion is certainly not nothing. So as far as Locke was concerned, not only

is every idea real and positive, but the causes of ideas must be real and

positive as well. Solidity. Locke singled out the idea of solidity

for special attention, identifying it as the idea that “seems the ... most

intimately connected with, and essential to body” (II.iv.1). This is something of a startling claim if

we think that the idea of solidity is an idea of sensation and recall what

was said earlier about the distinction Locke otherwise drew between perceiving

an idea of sensation and knowing what it is about the nature of objects that

is the ultimate cause of that idea.

But there are yet more incongruous features to Locke’s account of

solidity. He maintained that it is

impossible to define a simple idea of sensation. If anyone is unfamiliar with some simple

idea we are talking about, such as the colour red, all we can do is expose

them to the circumstances that will cause them to have that idea. We cannot otherwise explain what the idea

is (II.iv.6, cf. III.iv.11).

Occasionally, Locke treated solidity as just such a simple idea,

claiming that if anyone asks what solidity is, we must send them to their

senses to inform them (II.iv.6). This

is just what we would expect if solidity is an idea produced in us by touch

or the product of a tactile sensation.

As so understood solidity would be a particular feeling we experience

when we run into something — a feeling that can vary from the feeling of a

prick or pressure point to acute pain.

But elsewhere, Locke gave a very precise definition of solidity,

something that should be impossible if it is just a feeling. He defined it as the idea of resistance to

penetration. Supposedly, this is an

idea that we get through our sense of touch when we approach a body and find

that it does not allow us to enter the space it occupies. As such, it is a far from simple idea,

involving just “one uniform appearance.”

It is instead a complex made up of ideas of motion, collision, and the

consequences of collision, apparently including the idea of “resistance” to

compression and so the idea of what is in effect a repulsive force — a force

or power to resist motion in a certain direction. Even more extraordinarily, it is not a

feeling produced in us as a consequence of tactile sensation. It is a quality of a body that resides in

that object. Locke seems not to have realized that he

was speaking of “solidity” in two different ways, as a simple and indefinable

feeling produced in us by touch, and as a body’s quality of exercising a

repulsive force to prevent other bodies from entering the space that it

occupies. Not surprisingly, therefore,

it is far from clear how we are supposed to get the latter idea. Does the experience of the tactile feeling

somehow lead us to infer or intuit that we are encountering a body that is

exercising a repulsive force? Does the

experience involve the sort of direct awareness of this quality in bodies

that is involved in obtaining ideas of reflection? Locke never said. It is simply not obvious how Locke’s

account of the idea of solidity fits with his official position on sensations

as motions of body parts and ideas of sensation as perceptions of images

produced in the mind as a consequence of the nerves conveying motions to the

brain. Setting this aside, Locke distinguished

the idea of solidity from that of hardness.

Whereas solidity has to do with repulsion, hardness has to do with

attraction or cohesion. When the parts

of a body attract one another or cohere together so strongly that they resist

our attempts to move them relative to one another, we say the body is

hard. But very soft bodies, such as

water, can still be solid, in the sense of resisting compression. Locke considered hardness to be something

that comes in degrees and is relative to our own strength. The stronger we are, the sooner we can make

the parts of a body move relative to one another and the softer we consider

it to be. But solidity is something

Locke assumed to be absolute. It does

not come in degrees but is always entirely present. He did not believe, as we do today, that it

is in principle possible to go on compressing materials forever to produce

denser and denser things like neutron stars or black holes. Instead, like Whether

we move or rest, in whatever posture we are, we always feel something under

us that supports us and hinders our further sinking downwards, and the bodies

[that] we daily handle make us perceive that, while they remain between them,

they do by an insurmountable force hinder the approach of the parts of our

hands that press them. [II.iv.1] It is in part because of this absolute

nature (most other qualities come in degrees) that Locke considered solidity

to be the idea that “seems the ... most intimately connected with, and

essential to body” (II.iv.1). In fact,

he speculated at Essay II.iv.5 that

inertial force (“impulse”), cohesion, and hardness may simply be modes of

solidity. In opposition to Descartes,

he maintained that wherever we think there is some body, that is, some

material thing, we also think there is resistance or solidity. In making this claim, Locke was staking out

a very different position on our idea of the essential nature of body. Rather than say that our idea of body is

just an idea of a shaped and movable piece of extension, Locke insisted that

it requires something more: the additional idea of solidity or

impenetrability — the idea, in other words, of repulsive force. Remove this idea of solidity from the idea

of an extended body and it ceases to be an idea of body and becomes an idea

of empty space. Thus, for Locke, unlike for Descartes,

there is a distinction to be drawn between the ideas of space and of

body. The idea of body is the idea of

a solid, divisible, and movable extension.

The idea of space is the idea of a penetrable, indivisible and

immovable extension. We think that

bodies sit in space, which they penetrate perfectly and move through. We think that space and all its parts are

immobile, so that no part can be moved out of the vicinity of its

surroundings and space itself cannot be divided or broken. Locke justified this position on body

and space by appeal to experience.

Whenever our experience supplies us with an idea of something that we

consider to be a body, he claimed, we also find that it supplies us with the

idea of solidity. Descartes had tried

to undermine this view with the argument of Principles II.4 and II.11, where he had claimed that if all bodies

retreated from our hands when we attempted to touch them, we would still have

an idea of body. But Locke could have

replied that the thought experiment only proves that we can conceive of

bodies without having to conceive them to be hard, not that we can conceive

of them without having to conceive of them to be solid. Solidity is the property of resisting

penetration, and if bodies retreat from our hands as we approach them that

does not mean that they are not solid.

After all, as long as they retreat from our hands, the test to

determine whether they resist penetration has only been confirmed, not

disconfirmed. If they were not solid,

they would not retreat but would allow our hands to pass through them like mist. Locke could have asked what would happen if

there were an immovable wall just behind the bodies we reach out for. Would they retreat through the wall? Then there would be two bodies in one place

at the same time, which Descartes would hardly accept. Would they allow our hands to penetrate

their dimensions? Then we would not

think they are bodies, but empty space. Or would they resist the motion of

our hands with “an insurmountable force?”

Then solidity, and not just extension, is essential to body. Neither was Locke convinced by Descartes’s

arguments against empty space. For Locke, if you remove all solid, movable

extension from a container, there will still be something, namely penetrable

immovable extension, left over between its walls, and therefore the walls

will not be together. Locke reiterated these points, and

supplemented them with further arguments in favour of the existence of a

vacuum, over Essay II.xiii.11-27. Locke’s position on these matters was

seconded by ESSAY

QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Critically

assess Locke’s argument for empirism, as presented

over Essay II.i.5-7, ii.2-3, iii.1

and III.iv.11.

2. In the

mid-eighteenth century the French philosopher, Etienne Bonnot,

Abbé de Condillac, argued

that Locke had been too moderate in his empirism

insofar as he had allowed that we might be innately capable of performing

certain operations on our ideas and obtaining “ideas of reflection” from

reflecting on those operations.

According to the argument of Condillac’s most famous work, the Treatise on sensations, we learn to

perform all mental operations through having our attention focused in certain

ways as a consequence of the experience of pleasure and pain. Study Condillac’s work and explain whether

his “sensationist” reply to Locke is ultimately

successful.

3. Locke’s position

on the distinction between body and space was a controversial one, and many

philosophers in addition to Descartes found it difficult to accept. He offered further arguments for it in a

chapter specifically devoted to space, Essay

II.xiii.

Some of the principal arguments against the possibility of empty space

were articulated by Pierre Bayle in note I of the article on “Zeno of Elea”

from his Historical and critical

dictionary (Richard H. Popkin, trans.

[Indianapolis: Hackett, 1991], pp.377-385), with specific reference to

Locke’s inability to defend his position with anything more than objections

to the contrary position. |