|

20 Locke, Essay II.viii.7-26 Primary and

Secondary Qualities Over Essay II.viii.7-26 Locke considered the question of how our

simple ideas of sensation are related to the objects that produce them. Might

the qualities that appear in our ideas also be qualities of bodies that exist

outside of us? Might they at least

resemble qualities of bodies? Or might

there be nothing like the qualities of our ideas to be found in bodies? Alternatively might some qualities of our ideas

be qualities of bodies while others are not? In addressing these questions, Locke

divided our simple ideas of sensation into three different classes: i) ideas of solidity, extension or

bulk, and their various modifications, ii) ideas of sensible qualities like

colour, smell, taste, sound, heat and cold, iii) ideas of pleasure and pain. He proceeded to point out that people

have generally supposed that the qualities represented by our type (i)

and (ii) ideas are more or less exact replicas of properties existing in

external objects, and that we only have these ideas because external objects

have somehow managed to impress us with these qualities. In contrast, people have generally supposed

that type (iii) ideas of pleasure and pain do not resemble anything to

be found in external objects, even though they are also caused by these

objects. Type (iii) ideas are supposed to exist only in the mind, and

only when they are perceived. Locke’s main point over this part of

the Essay is that while the

tradition is right about type (i) and type (iii) ideas, it is wrong

about type (ii) ideas. The main reason Locke had to offer for

this position is given in Essay

II.viii.11. Locke there claimed that

the only way in which one body can be conceived to act upon another is by

impact. This requires us to ascribe

motion, solidity, and figure to bodies, since to impact one another bodies

have to be moving and solid, and to be solid they have to take up a space of

some figure. However, it also means

that we must consider all of our ideas to be products of the motion, solidity

and figure of bodies, rather than to be due to some quality in the bodies

that bleeds out of them and into our sense organs. For, if all action of one body on another

requires impact, then the action of bodies on our sense organs must also

require impact; and that means that bodies must be supposed to affect us

through being moving, solid and figured, and not through transmitting other

qualities. QUESTIONS

ON THE

1. Explain the

difference between qualities and ideas.

2. What features

must a quality have if it is to be considered primary?

3. How do the

secondary qualities differ from the primary, if at all?

4. How do the

tertiary qualities differ from the primary and the secondary, if at all?

5. How is it

possible for one body to act on another?

6. Given that

external objects are not only not united to our minds but even sometimes set

at some distance from us, by what means do we come to perceive their original

qualities?

7. When Locke

wrote in II.viii.15 that “the Ideas,

produced in us by these Secondary Qualities, have no resemblance

of them at all,” what were the ideas he was referring to, and what were the

secondary qualities that he had in mind?

8. What produces

the idea of the motion and shape of a piece of manna in us? What produces the ideas of sickness, acute

pains, and gripings in those who have eaten a piece of manna? What produces our ideas of the whiteness

and sweetness of the manna?

9. What is the

only effect that the pounding of an almond can produce in the almond? What effect does the pounding of an almond

produce in us when we perceive it? 10.

Under what conditions do we have an idea of the

thing as it is in itself? NOTES

ON THE The topic of Essay II.viii.7-26 does not fit very well with the idea of doing

a critique of the human knowing powers by means of the “historical, plain

method” of investigating the origin of our ideas, their nature, and the

conclusions that can be drawn from them.

Instead of starting from ideas and determining what can be inferred

from them, Locke here simply presupposed the existence of external objects,

presupposed that these objects affect us, and went on to inquire how our

ideas might be related to them. However, what Locke later described as

“this little excursion into natural philosophy” (II.viii.22) is not entirely

unjustified if we consider that, unlike Descartes, he did not think that he

first needed to prove the existence of bodies from absolutely certain first

principles. For him, it is enough that

it should be likely that there are bodies.

Granting that it is indeed likely, the question of the relation

between our ideas and bodies naturally arises, and Locke thought it would be

wise, right at the outset, to get clear about which features of our ideas

might even possibly be supposed to be resemblances of qualities in

bodies. This is especially the case

since, as he thought, people have generally taken things like colours, heat

and cold to be qualities in bodies when in fact they can be nothing more than

ideas in us. He began by drawing a distinction

between ideas in us and qualities in bodies. Whatsoever the Mind perceives

in it self, or is the immediate object of Perception, Thought, or Understanding,

that I call Idea; and the Power to

produce any Idea in our mind, I

call Quality of the Subject wherein

that power is. [II.viii.8] The inference seems solid enough. If there are ideas in us and we are not

ourselves responsible for producing them, then there must be something in

things other than us that is. Consider

whatever it is in a thing that does this to be a quality of that thing. But what might such qualities be? Locke needed to come up with some sort of

test for discriminating which, among the various things we find in our simple

ideas, might resemble qualities actually existing in bodies. He fixed on the same criteria Qualities

thus considered in Bodies are, First such as are utterly inseparable from the

Body, in whatever estate soever it be; such as in all the alterations and

changes it suffers, all the force can be used upon it, it constantly keeps;

and Such as sense constantly finds in every particle of Matter [that] has

bulk enough to be perceived, and the Mind finds inseparable from every

particle of Matter, though less than to make itself singly be perceived by

our Senses [II.viii.9] Compare We might wonder why Locke thought

these are useful criteria for identifying the “first” qualities of

bodies. After all, it is not as if we

see the bodies themselves and so can discern from experience that all bodies

in fact have certain qualities and that no process in nature ever destroys

those qualities. We can only see our

ideas. Unfortunately, Locke provided

us with no enlightenment on this score.

The most likely answer is that he may have thought that if any

features of our ideas could be ascribed to bodies, they would be those that

are present in all of our ideas of bodies. Applying this rule, Locke determined

that all bodies must be solid (for reasons already considered in the previous

chapter), and also that they must be extended. For, even though bodies may be divided,

division does not destroy their extension, but merely cuts it up into

separate pieces that can be moved apart from one another. Unlike Newton, however, Locke did not list

gravitational mass among the qualities that must be admitted among all bodies

(action at a distance seems to have been simply too much for him to accept,

though in later editions of the Essay

he silenced his objections to it in deference to Newton’s results), and he

speculated that inertial mass and hardness may be simply modifications of

solidity (II.iv.5). Insofar as bodies are admitted to be

solid and extended, they must also have all the qualities that arise from the

ways solidity and extension can be modified.

They must have inertia (which Locke took to be an effect of solidity

[II.iv.5]), hardness, figure, size, orientation, and mobility, and they must

be divisible into parts. These parts

in turn must have their own inertia, hardness, figures and sizes, and

depending on how they are ordered and interlinked in composite bodies, they

create different textures. There is another reason for concluding

that all bodies must have qualities of solidity and extension. Recall that Locke defined a quality as a

power in a body to produce an idea in us.

Locke also took it to be “manifest” that the only way that one thing

can act on another is by impulse, that is, communication of motion as a

result of impact or collision (Essay

II.viii.11). (Hence, his inability to

accept gravitational mass among the primary qualities.) It would have to follow that insofar as

bodies have powers to produce ideas in us, those powers must involve

impulse. But impulse presumes motion

and solidity, and motion presumes some number of things placed at different

locations over time, situated in some way with respect to one another to

constitute a shape of a certain size.

So all of the qualities that Locke identified as primary are necessary

if bodies are to exert a power to bring about ideas in us in the only way

Locke considered action to be possible, by impulse. Looking at things in this way led

Locke to conclude that people are in fact right to take their type (i) ideas

to be reflections or resemblances of qualities that are actually in

bodies. (Interestingly, Locke did not,

as was speculated in the previous chapter concerning solidity, take our type

(i) ideas to be direct perceptions of the primary qualities in bodies. Instead, he here took them to be images or

resemblances of such qualities. “The Ideas of primary Qualities of Bodies, are Resemblances of them, he

wrote, and their Patterns do really exist in the Bodies themselves,” he wrote

at II.viii.15, suggesting that the idea is one thing, the quality another,

even though they may resemble.

II.viii.7 similarly worries which of our ideas are “Images and Resemblances” of qualities in bodies,

not which are direct perceptions of those very qualities as they exist in

bodies.) However, Locke did not think

that the solidity, shape, and motion of bodies are directly communicated to

the mind, to produce our type (i) ideas.

Because he took it to be “manifest” that the only way bodies can bring

about ideas in us is by impulse he could not countenance any direct

connection between external objects and our minds, particularly in the case

of vision. Impulse requires contact,

and bodies are not in contact with our minds, or even with our brains.

Indeed, some of the bodies that we sense are set at quite some distance from

us. Reflecting on this fact, Locke

concluded that if we nonetheless get type (i) ideas from these bodies, it must

be because they emit or reflect a stream of insensibly small particles

towards our sense organs. But even the

objects of touch do not touch our brains, but only the exterior surface of

our sense organs, which produces alterations in the way the nerves or the

particles flowing through the nerves are moving. These motions are transmitted to the brain

and the result of this process, a motion of the parts of the brain, likely

bears only the most remote similarity to the body that originally caused

it. However, Locke supposed that the

particular ideas of extension and solidity that are produced in the mind when

particular motions occur in the brain do, happily or because of divine

providence, at least bear some degree of resemblance to the macroscopic shapes,

motions, and solidity of the bodies that originally affected us. Very often, the shapes we see are

distortions of the actual shapes of the objects, and the distortions are

mathematically related to the actual shapes and are distorted in the ways

that they are in accord with constant laws, the laws observed by painters

when depicting how the shapes and sizes of objects are changed as a

consequence of distance and perspective. Locke went on to claim that while our

type (i) ideas are at least “resemblances” of qualities in bodies, it is a

vulgar error to suppose that the type (ii) ideas also resemble qualities in

bodies. In fact, he claimed, we have

more reason to suppose that they are like the type (iii) ideas — that they

only exist in us and only exist when perceived, though they are caused by

something that endures in external objects independently of being perceived. It is important to understand the path

of Locke’s argument. Locke did not

claim that we can know that our

type (i) ideas are resemblances of qualities in bodies, but that our type

(ii) ideas are not. He rather argued

that we have a number of good reasons to doubt that our type (ii) ideas

resemble any qualities actually inhering in bodies. These same reasons do not, however, apply

to our type (i) ideas (Essay

II.viii.21 contrasts the different sensations of heat and cold that we can

get when we immerse a hot and a cold hand in the same bucket of water with

the sensations that we have of the figures of bodies, which according to

Locke never vary regardless of what state our hands are in). Therefore, while we have reason to doubt that our type (ii) ideas

resemble qualities in bodies, we have no reason to doubt that our type (i)

ideas do so. This does not mean that

we can claim to know or be certain that our type (i) ideas do resemble

qualities in bodies. At best it means

that we have no good reason to doubt this claim, and so can believe it is

probably true. Locke offered five main reasons for

doubting that type (ii) ideas resemble qualities in bodies. The first is to be found at

II.viii.16. Locke there observed that

type (ii) ideas can, as it were, shade off into type (iii) ideas. Warmth and cold, for example, are type (ii)

ideas that turn into pain as they are intensified. This is an indication that type (ii) ideas

cannot really be distinct from type (iii) ideas. They are simply lesser degrees of the same

phenomena that are present in more intense degrees in our type (iii)

ideas. But everyone is agreed that

type (iii) ideas exist only as ideas in us and are not qualities in

bodies. If the type (ii) ideas are

simply less intense degrees of the type (iii), then they ought to exist only

as ideas in us as well. Locke’s second argument is alluded to

in the last clause of II.viii.16 and laid out more fully in II.viii.18. (II.viii.17 does not offer an argument but

simply further describes the theory and is passed over here.) At the close of paragraph 16 he observed

that if the only way change can occur is by impulse (as was claimed in

II.viii.11), then the only way any ideas whatsoever, including our ideas of

sensible qualities, can be brought about in us is by motions of solid, shaped

parts. But if all that needs to exist

in order to cause our ideas of sensible qualities is the motion of shaped and

solid particles, then it would be extravagant to suppose that bodies must

also have qualities that resemble colours, smell, heat and cold, and other

sensible qualities. II.viii.18 argues

for this same point by means of an extended discussion of a piece of manna. (Manna was an 18th century medicinal

concoction used to induce nausea and vomiting. It was white and sweet and was baked up in

pans like cake and then cut up in squares.)

Locke’s point is that the type (i) ideas we get of the manna’s shape

and motion are supposed to be the result of the aggregate shape and motion of

its insensibly small parts. Similarly,

the type (iii) ideas we get of pain in the guts are supposed to be the result

of exactly the same cause: the motion of the insensibly small, shaped and

solid parts that go to make up the manna, acting on our intestines. Why, therefore, asked Locke, should we

suppose that the whiteness and sweetness must alone have some other, unique

cause, qualities actually resembling whiteness and sweetness? It is not as if it is any more mysterious

how colourless, tasteless particles could produce ideas of colour and taste

than it is how they could produce ideas of cramping and pain, yet we have no

problem accepting the latter consequence.

By parity of example we ought to accept the former. Locke’s third argument is given over

II.viii.19, and turns on the observation that our type (ii) ideas can

disappear even though the bodies remain and are not thought to have undergone

any alteration. Locke instanced the mineral, porphyry, which looks to be red

and white, but which does not have those qualities in the dark. Since the red and white disappear in the

dark, but we do not think that the porphyry is destroyed or altered by shutting

off the light, we must conclude that these colours are not really qualities

in the body, porphyry, but rather results of the way light affects our

senses. At the very least, they are

not qualities bodies have to have in order to be conceivable and that they

have to retain through all eventualities. Locke’s fourth argument is found at

II.viii.20. He there observed that

operations that can only plausibly be supposed to change the shapes,

arrangements, and motions of the insensibly small parts of bodies lead us to

have different type (ii) ideas.

Pounding, for instance, is an operation that can only be supposed to

break the extension of a body up into a number of separately movable parts,

and so make it softer. But pounding

also changes the colour and taste of an almond. Since all that pounding can really do is

alter the almond’s texture and hardness, the changed taste and colour must be

merely effects of the changes in the texture and hardness on our senses of

vision and taste, and not independently existing qualities in the bodies at

all. Locke’s final argument is found at

II.viii.21 and takes the form of an inference to the best explanation. He there observed that the same body can

simultaneously give us different, incompatible type (ii) ideas. The same

bucket of water, for instance, can simultaneously feel warm to a cold hand

and cold to a warm one. Locke pointed

out that it is difficult to account for this fact on the supposition that our

ideas of colour or heat and cold are caused by resembling qualities that

migrate into us from the bodies that affect us. Since the ideas are incompatible, both

cannot simultaneously exist in the object.

At least one of them must be merely an idea in us and not a quality in

the body. But which one is the real one and where does the unreal one come

from and how do we know that the real one does not come from the same sort of

causes that produce the unreal one rather than from a resembling quality in

the object? All of these difficult

questions are avoided, Locke claimed, if we accept an alternative

theory. If we take the colour and the

degree of temperature to be merely ideas produced in us as a result of bodies

hitting our sense organs, then we can take the previously existing state of

the sense organ to enhance or impede the motion and so alter the character of

the sensation that is communicated to the brain. And altered sensations can be expected to

produce different ideas in the mind. Thus, taking type (ii) ideas to be

produced in us by the impact of solid, moving parts provides a better

explanation of the phenomena of perceptual relativity than does the

supposition that they are caused by resembling qualities in the bodies. Summing up all of these considerations,

Locke claimed that there are three types of qualities in bodies, and three

types of ideas in us: First, there are primary qualities in

bodies. These qualities are solidity,

extension, and their modifications.

When bodies are aggregated together in large enough numbers to build

up composites of sufficient size to be visible or tangible, our type (i)

ideas can be considered to be resemblances of the macroscopic solidity, size,

shape, and motion of the composite bodies.

However, when the parts composing an object are too small for us to be

able to perceive, or when they lie below an opaque surface that has not been

anatomized, our ideas are less accurate. Locke considered that in addition to

the primary qualities of extension, solidity, and their modes, bodies also

have a further set of qualities. He

called these qualities powers. When we

consider what bodies can do to us, we get the idea that they have the power

to bring about ideas of sensation in us, and when we consider what they can

do to one another, we get the idea that they have the power to change one another. If all motion is due to impact, these

powers must ultimately arise from something solid, shaped, and moving hitting

something else. But when we cannot see

what it is in bodies that brings about these effects, our ideas of the powers

in things are only “relative.” The

power is really some arrangement of solid, shaped, moving, particles. But since this arrangement of particles is

invisible, we identify the power relative to its sensible effects. It is particularly important to

distinguish between secondary qualities as they are in bodies, and type (ii)

or non-resembling ideas as they are in us.

Colours, smells, tastes, and so on are not secondary qualities. They are type (ii) ideas brought about

by the secondary qualities of bodies.

As effects of the secondary qualities in objects, which are powers to

affect us arising from the insensibly small bulk, figure, number, situation,

and motion of particles, they may serve as “relative” ideas of those powers,

and this can lead to some confusion.

Since we can only think of the different powers by referring to their

effects, not by directly discerning the powers themselves, we tend to

substitute our ideas of the effects in the place of that of the powers, of

which we have no idea. This can happen

easily and inadvertently in language, where it is simply easier to talk about

the “redness” in a body than to employ a circumlocution like “the power in

the body to bring about the idea of red in us.” Locke warned us that he himself would often

speak this way, even though he knew better.

We need to keep in mind, therefore, that even though he may on many

occasions speak as though he takes colours, scents, tastes, and the like to

be secondary qualities in bodies, his considered position is that the

secondary qualities are powers due to the arrangement of solid, shaped, and

moving parts and do not resemble our type (ii) ideas in any way. If they resemble anything, it is our type

(i) ideas. To confuse colours, smells,

tastes and the rest with secondary qualities in bodies is to commit just the

error Locke was attempting to expose over II.viii.7-26. Essay II ix.1-4,8-9; x.1-2;

xi,1,4,6,8,9,15,17 Perception and

other Simple Ideas of Reflection For Locke, in addition to the ideas

that we get from sense, which refer to objects outside us, there are ideas we

get from reflection on the operations of our own minds. It is through these ideas that we first

become conscious of what our own minds do to the ideas they have previously

received. Through them, we learn how the mind processes ideas to generate

knowledge, belief, opinion, fantasy, and even experience itself. Essay II.ix-xi is devoted to an examination

of some of the main ideas of reflection and the operations they refer to. These main operations are perceiving,

remembering, discerning and comparing, compounding and repeating, naming, and

abstracting. QUESTIONS

ON THE

1. Can we have

ideas that go unnoticed by us?

2. What is the

idea immediately imprinted on the mind when we see a black or golden globe?

3. What makes it

“evident” that this is all there is to the immediate idea?

4. What was

Molyneux’s question and what was his reason for answering this question in

the negative?

5. What moral did

Locke draw from Molyneux’s negative answer to this question?

6. Explain

Locke’s distinction between the role played by “perception of sensation” and

“idea of judgment” in visual perception.

What is immediately perceived as a consequence of sensation and what

is judged?

7. What is wrong

with viewing memory as a storehouse for ideas we have had in the past? What is memory if not a storehouse?

8. How is it that

particular ideas can be made to become general? NOTES

ON THE Perceiving consists in attending to

the effects our senses convey from objects to the brain. Locke maintained that, unless the mind

actively attends to or “perceives” these effects, ideas will generally not

arise from sensation. There are

exceptions — bright lights, fast moving objects, cuts, burns, pinches, and

loud noises tend to intrude on the mind, draw its attention, and force it to

form corresponding ideas of colour, motion, pain, and sound. But objects can often have an influence on

our senses and brains that goes unnoticed and does not lead the mind to have

any perceptions. This is readily

exemplified by the case of our sensations of pressure and gravity. Up until this moment, you have likely not

been aware of the feeling of your chair or the ground pressing up on you from

below. Yet the chair and the ground

have all along been having an influence on your sense of touch, and your

sense of touch has all along been transmitting something to your brain as a

consequence of being so affected. But

until you chose to attend to them, those sensations did not produce any ideas

of solidity or pressure in your mind.

In this case, your ideas are not simply passively received as a result

of stimulation of your sense organs, but depend on a special effort of

attention. That act of attention,

whether forced upon us by the violence of the sensation of the product of an

effort, is what Locke called perceiving. Note that Locke did not define

perception as the operation of attending to ideas that already exist,

unnoticed, in the mind. The process of

perceiving or attending is required to bring ideas into being. If that process is not performed, the sense

organs can still transmit motions or impressions into the brain and those

motions and impressions will exist in the brain. But they will not cause ideas. They cause

ideas only with the cooperation of the perceptual faculty of the mind. This cooperation can sometimes be compelled

(as in the case of very strong sensations, as noted earlier), but if it is

not compelled, ideas will simply not be created, even though the appropriate

impressions and motions exist in the brain. There can be no unperceived

ideas, therefore. Ideas only exist

insofar as they are perceived. Locke went on to note that there is

much less happening in perception than many suppose. This is because acts of perception can be

overlaid with judgments from which they have not been properly distinguished. Usually, when we judge, the act of

judging is explicitly a two-stage process.

There is something that is given to us in perception as information or

premises, and then a conclusion is drawn from this information. We are perfectly aware that the information

is one thing and the conclusion drawn from the information something quite

different. However, in cases where we

have been called upon to make the same judgment over and over again, the

judgment can become so automatic that we are not aware of making it. We get the information by perception, make

the judgment, and then forget the information we based the judgment on, and

forget the act of judgment and just think of the conclusion, so that it seems

to us as if we are simply perceiving the conclusion, rather than perceiving

the original information and then judging that it entails the conclusion. Locke gave an example. A sensation is transmitted from the senses

to the brain. The mind attends to this

sensation. In very young children,

attention to this particular type of influence naturally and originally

produces the idea of a flat circle, variously coloured. However, children discover as they grow up

that their visual ideas of flat circles, variously coloured, are associated

with tangible ideas of globes, and these globes are seen, upon being turned

about, to actually be of a uniform colour.

As a result of this experience, an act of judgment intrudes to

influence our perception. In adults

the original idea of a flat circle variously coloured is taken to be a sign

of a uniformly coloured globe and the transition from the one idea to the

other is so easy and rapid that the initially received idea is transformed

into the associated idea. The

operation is quite extraordinary, when you think that it is quite difficult

to convince adults that they see anything other than a uniformly coloured

globe. They are so little aware of

really seeing something quite different and judging from that appearance that

they can hardly be convinced that they do not immediately see a uniformly

coloured globe. It is only when they

are forced to do something like paint a picture of the globe that they

suddenly discover, as they attempt to replicate the exact appearance in

coloured paint on canvas, that globes are not uniformly coloured and that

cubes are not seen to have three square faces (on the visible side, when

viewed from an oblique angle). In giving this example Locke supposed

that we originally see in just two dimensions. This is something that he took to have been

made evident by the practice of painters. Locke seems to have thought that

when we go to paint, we are forced to attend more closely to what we really

see than we normally do. Painters who

go to paint a golden or jet black globe actually see, upon close inspection

of this object, that it is not in fact of a uniform colour, but that the

colour shades from bright to dark over various parts. Then, when they go to replicate this actual

appearance on canvas, they discover that their painting, despite being made

of varying colours placed on a flat surface, actually looks rounded and

uniformly coloured, like a uniformly coloured globe, whereas if they had made

it all one colour, it would have looked flat and circular. Something similar happens with

cubes. We define cubes as three

dimensional figures enclosed by six squares set perpendicular to one

another. And this is what they feel

like to the touch. It is also what we

naively think they look like. But it

is impossible to make an accurate model of a three dimensional object on a

two dimensional surface, like a canvas.

So it ought to be impossible to draw or paint a cube. However painters discover, perhaps by

setting up a fine, wire grid before their eyes, drawing squares on canvas,

and then copying the appearance of a cube seen through the wire grid onto

canvas, that cubes are not actually seen to have the shapes they are felt to

have. They are seen in

perspective. And when this perspective

appearance is reproduced on canvas, the drawing on the two-dimensional

surface takes on an appearance of depth in three dimensions.

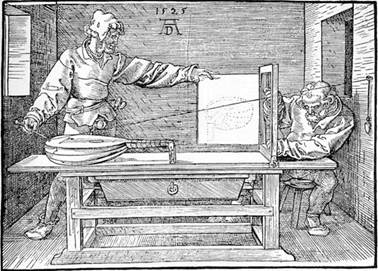

Woodcuts

by Albrecht Dürer, illustrating the use of

devices to assist us in drawing what we actually see so as to be able to

properly represent objects in perspective.

The spire in the top diagram is necessary for the draughtsman to keep

the eye constantly positioned at the same point while viewing through the grid. This experience convinces us that the

sensations we originally receive from vision must be like what the painter

paints onto canvas. Painters are forced by their craft to paint what they

really see. And we, who look

attentively at paintings and see how they lead us to, as we say, “perceive”

depth, discover that we are not really perceiving at all, but making

judgments based on what is really there, which is not in depth at all, but

flat. The features painters put into paintings

must be the very features of the original visual ideas that lead us to infer

depth. If Locke was right about this, then

those who have not yet had the relevant experiences should still see the

original visual ideas without the modifications our experience subsequently

leads us to impose on them. Thus, very

young children should see in only two dimensions. This is a controversial issue, and it

touches on a dispute between Locke and Descartes. Descartes shared Locke’s supposition that

we originally see in only two dimensions. But, when discussing the means

whereby we come to visually perceive depth in his Optics, he had declared that some of these means involve “as it

were an innate geometry.” That is,

Descartes had supposed that we are simply innately so constituted that, on

the occasion of experiencing certain two-dimensional visual ideas, we

automatically judge their three-dimensional significance. Locke’s rejection of innate knowledge

did not dispose him to accept Descartes’s account of depth perception. In opposition to Descartes, he wanted to

insist that it is only after we have discovered through experience that

certain visual ideas correspond to certain tangible ideas that we are enabled

to make judgments concerning visual depth. Unfortunately, Locke and Descartes

could not resolve their dispute by introspection. None of us is any longer in a position to

remember how things originally looked to us in the first weeks after birth,

or whether we had to learn to associate two-dimensional and chromatic

features of our infantile visual experiences with distances outwards along

the depth axis. Neither could the

dispute be resolved by approaching very young children and asking them

whether they are able to see depth. By

the time children have acquired the verbal and intellectual abilities to

understand the question, they are too old to remember what their original

visual experiences were like. The

Molyneux Question. This last

reflection led Locke into a fascinating digression on what adults, blind

since birth, but intellectually sophisticated, able to communicate, and

familiar with geometrical concepts learned from the sense of touch would tell

us upon acquiring the power of vision. One of his friends, William Molyneux,

had earlier posed a question on this topic — a question that has since become

one of the central topics of perceptual psychology. What would happen, Molyneux asked Locke, if

a blind person, who had learned by touch to distinguish between a cube and a

sphere were made to see and then shown a cube and a sphere? Would the blind person be able to tell

which was the cube and which the sphere just by looking at them, without

first touching them? Both Molyneux and Locke speculated

that the answer to this question would have to be no. They thought that the spatial features of

visual experience are not enough like those of tactile experience to lead a

previously blind person to be able to confidently declare what objects they

are seeing just based on the visual appearance of those objects. The previously blind person might see two

dimensionally extended coloured patches that are in fact circular or square

in the sense of having a circumference everywhere equidistant from the center

or having four equal sides and four equal angles. But Locke and Molyneux did not think that

this means that the previously blind person would understand their visual

experience in all the same ways that we do — that they would straightforwardly

take it to be an experience of the all the same objects that we do. This is because the objects of visual

experience are not simply seen but inferred from what is seen, and the

previously blind person has not yet learned how to draw those inferences from

what is seen to the nature of the objects responsible for that

appearance. The previously blind

person would not be able to identify distances of the parts of objects

outwards from one another in the direction of depth, and so would not see

three dimensional objects like cubes and spheres, much less infer that they

are uniformly coloured. Consequently,

when confronted by something like the variation in colour of a globe, the

previously blind person might draw distinctions between colour patches where we

see just one uniform colour. And vision

would present the previously blind person with nothing analogous to the

tactile sensation experienced when touching a cube. We can feel all six faces at once, but we

cannot see them, and the faces we do see may be seen in perspective, which

for anyone who accepts that we see in only two dimensions means that they may

not be seen as square or made of sides of equal lengths. As Molyneux put it, the previously blind

person is in no position to infer that, simply because something looks to have some shape it would also

be felt to have some shape —

particularly if the thing looks to

have a two-dimensional shape

but the question asks about a three-dimensional

shape it does not look to have, and if the two-dimensional shape that the

object looks to have is a function of where the previously blind person

understands the boundaries between differently coloured regions to be drawn. We have all had the experience that

things that feel a certain way do not always look the way they feel. For example, a straight pencil looks bent

when half inserted in a glass of water.

Solid objects cast different images on the eyes depending on how they

are turned. What appears smooth,

small, and round from a distance may look craggy, large, and square from

close up. Any object looks to have the

shape of a dot if viewed from a sufficient distance under sufficient

illumination. And so on. But even if the previously blind person

were to make the leap to suppose that because objects look to have a certain

shape that they would be felt to have that shape as well, the person might

well end up describing their visual experience in very different terms than

we do, because the two-dimensionality of visual experience is more apparent

to them than to us, and because the ways different colours can fall on same

surfaces and same colours on different surfaces might lead them to draw

figure/background distinctions in a different way than we do. Consequently, when asked “which is the cube

and which the sphere” when nothing they

see looks to them like either a cube or a sphere, they would quickly get the

idea that objects must look very different from the way they feel, and would

hesitate to answer the question with any confidence. We might ask what would happen if the

blind person were told in advance that objects seen from close up generally

look the way they feel, or that each point of the three dimensional objects

of touch projects onto the visual field by lines drawn from that point,

intersecting at the center of the eyeball, and hitting a concave surface of

the back of the eye behind that point, so that the sensory stimulus

originally produced by visual objects is a concave, two-dimensional

projection of those three-dimensional objects. Locke and Molyneux would probably answer

that in that case the experiment would be corrupted and nothing would be

learned from it. Molyneux’s question

was whether someone newly made to see would immediately perceive the same

objects we do or would see something so different from those objects that it

would take a guess or an inference to arrive at an answer. If you tell the blind person in advance

everything that they need to know in order to make a judgment about which

object is which, then you won’t be able to tell whether they are just

immediately seeing or instead drawing an inference from what they immediately

see. Those who have since considered

Molyneux’s question have often forgotten the context in which it was asked,

and the presuppositions about the nature of visual experience that Locke and

Molyneux carried to their study of that question. For instance, Leibniz, writing a bit later,

claimed that the blind person ought to be able to associate the prickly feel

of a cube with the existence of angles in the square colour patch experienced

in vision and so discriminate the visual cube from the visual sphere on first

sight. And Reid, a generation after

that, maintained that Nicholas Saunderson (a famous English mathematician and

geometer, who was blind, but understood the laws of geometrical projection

very well), would be able to tell which was which as long as he was told how

light rays are reflected from objects and refracted onto the retina by the

lens of the eye. Both Leibniz and Reid

missed the point that Molyneux was not asking whether the previously blind

person could make an educated guess or a correct judgment. Molyneux and Locke were trying to get an

answer to the question of what the previously blind person would immediately

see, not what they would be inclined to guess or judge about what they saw. Other philosophers and psychologists,

beginning with Berkeley and Condillac, have wondered whether the previously

blind person would at first be able to see any shapes, or even any spatial

order of colour points at all.

Molyneux might have welcomed that question as an even more compelling

way of making the point that there is so little affinity between visual and

tactile experience that a newly sighted person could not confidently claim to

be able to perceive objects by vision.

But Locke might also have seen it as a worrying challenge to his

position on primary qualities. If the

objects of vision are effectively not immediately seen to be in space at all,

then extension and motion cannot be assumed to be universal qualities of all

the objects of sensation. And since

solidity cannot be understood apart from motion and extension (since it has

to do with resistance to entry of a moving object into a space), nothing is

left that could be a primary quality. Locke’s purpose in raising the

Molyneux question was programmatic.

“This I have set down, and leave with my Reader[s],” he wrote towards

the close of Essay II.ix.8, “as an

occasion for [them] to consider, how much [they] may be beholding to

experience, improvement, and acquired notions, where [they] think, [they

have] not the least use of, or help from them.” Over subsequent parts of Essay II, Locke intended to argue that

a number of ideas that Descartes and others had supposed to be immediately

perceived by a direct inspection on the part of the understanding —

ideas like those of substance, infinity, intelligible extension, and

identity — are in fact built up by mental operations

(such as compounding, comparing, and abstracting) from more primitive ideas

that are originally given through sensation. The consideration of the Molyneux question

served as a sort of preparative for that argument. Locke’s thought was that if we could be led

by consideration of the Molyneux question to appreciate that a significant

number of the ideas that we think are directly and immediately perceived by

us are actually worked up by unnoticed mental operations performed upon more

primitive and simpler ideas, then we would be more receptive to what he had

to say in the remainder of Essay

II. But whatever opportunities the

question might have offered to Locke to make other points, it is also

troubling. It is not clear what

originally motivated Molyneux to ask his question, but the fact is that what

Locke said about visual perception in the first edition of Essay II.ix.8 does not sit well with

what he had said at Essay II.v

about ideas of space and extension coming from more than one sense, and at Essay II.viii.21 about the distinction

between primary and secondary qualities.

Locke seems not to have noticed this and to have viewed Molyneux’s

question as a further illustration of what he had to say at II.ix.8 rather

than as a challenge to his earlier claims.

But if the fact that the same bucket of water can appear warm to a cold

hand and hot to a cold hand entails that heat and cold must be merely type

(ii) ideas in us rather than primary qualities of bodies, then by parity of

example the fact that the same object can appear round to the touch and flat

to they eye should entail that round and flat must be merely type (ii) ideas

in us rather than primary qualities of objects. And the same object does appear round to

the touch and flat to the eye if we accept Molyneux’s claim that the visual

and tactile appearances of the same object are so different that a person newly

made to see could not, at first sight, apply the same names to both. If shape, size, and position are not

qualities that are common to both sight and touch, but visual shape is

distinct from tangible shape, visual size from tangible size, and visual position

different from tangible position, then with what right do we consider these

to be qualities of objects rather than features special to specifically

visual and tactile ideas? Had this

been what motivated Molyneux’s question, Locke might have had a harder time

endorsing Molyneux’s negative answer — or at least noticed a need to

reconcile a negative answer with his other views. There were no actual tests of the

Molyneux question made in Locke’s day, though a generation later an English

physician, William Chesselden, removed cataracts from a boy’s eyes and made

careful observations on the boy’s reactions — observations that appeared to

confirm Locke’s and Molyneux’s positions on the question. Subsequent work has been more ambiguous and

has tended, if anything, to establish Berkeley’s and Condillac’s conjecture

that visual experience is far more complex and multi-faceted than Locke and

Molyneux had imagined. Contemplation

and Memory. Locke noted

that we have a capacity to hold an idea we have once perceived in mind even

after the sensation that caused it is no longer occurring in the brain. Locke called this capacity contemplation. Memory, in contrast to contemplation,

is the capacity to have ideas that have been perceived in the past. Obviously, we do remember things, and we do

so all the time. But memory is an

extremely difficult operation to account for.

There is something almost paradoxical about it. We cannot remember something off in the

past the way we see something off in the distance, by just looking and seeing

it faint and obscure on the horizon.

For the past no longer exists.

Given this fact, it is tempting to say that what we do is contemplate

some left over trace or echo of the past object that continues to exist. Hobbes, insofar as he treated our

sensations as producing motions that continue to reverberate in the brain

after the time of their initial impression, took such a position. However, Locke was explicit that memory

cannot involve storing the echoes or traces of past ideas away in some filing

cabinet of the mind, like so many pictures or documents, and then pulling

them out again when needed. Were we to

accept that view, we would have to accept that ideas continue to exist when

not perceived and Locke did not want to make that supposition. Rather, he took memory to be a capacity to

recreate ideas we have had before and that have since disappeared, even

though the sensory stimulus that originally produced them is no longer

present. But then how do we distinguish these

ideas from ideas currently being produced in us? How do we know that we are

remembering? We cannot say that this

is because there are no motions or impressions currently being communicated

by our senses to our brains to cause the ideas, because all that we are ever

aware of is our ideas, not the activities in the brain that are supposed to

cause them. Neither can we say that it

is because we are aware of

deliberately producing them. While we

do deliberately produce memories, this does not suffice to distinguish memory

from imagination. Given that we have

no innate ideas, imagination is, like memory, confined to reproducing ideas

we have had before, in sensation or reflection. The only difference is that in memory we

reproduce ideas in the same sequence we have had them in the past, whereas in

imagination we are not bound to do this (though it is not impossible that we

might by accident). But since we are

now attempting to account for memory, we cannot say that memory is an ability

to reproduce ideas in the sequence they originally occurred in experience,

because how would we know what that sequence was? To presume that the order in which ideas

are produced is guided by knowledge of the sequence in which they originally

occurred is to presuppose the very thing we are trying to explain, a memory

of the order in which the ideas originally occurred. To suppose that we just have an ability to

reproduce ideas we have had in the past without being guided by any left-over

trace or impression of the original sequence is to admit that we are only

capable of imagination and leave it a problem how we ever manage to remember. To solve this problem Locke declared

that when we create an idea in memory we form the further idea that this idea

was sensed at some time before, and attach this idea of “beforeness” to the

idea we are currently creating. However, this position raises further

problems. To remember an idea, on this

account, is to attach to a currently existing idea the further idea that it

was had before. But what could make us

think such a thing, if the currently existing idea exists now, rather than

earlier? To answer that we remember that an idea just like it was

had earlier (or “before”) is unacceptable, because Locke is here supposed to

be explaining what memory is. To say

that to remember is to now have an

idea that you remember was had more

vividly in the past is not an explanation of what memory is because it

employs the very notion we are trying to explain as part of the explanation.

So it looks like Locke would have to say that we are simply innately so

constituted that when we perform the operation of remembering we

simultaneously produce an idea of beforeness, which we attach to what we

remember. One problem with this approach is that

beforeness is something that comes in degrees. How do we know how much before or how

earlier to consider a remembered idea to be? What gives us the capacity to

not merely reproduce the idea, but keep track of how much time has passed

since we had it so that we can attach the appropriate amount of “beforeness”

to it? It is not clear how these

questions could be answered without presupposing that we somehow remember how

long it has been since we last had the idea, though how we remember anything

is just what is supposed to be explained). Another problem concerns how Locke

would account for the origin of the idea of beforeness. He could not take it to be a simple idea of

sensation, like our idea of red, because the idea of beforeness is not simple. It is the idea of a relation that obtains

between two things, an earlier one and a later one. For Locke, ideas of relations arise as a

product of the operation of comparison.

We consider two ideas together and discover some relation to hold between

them. But in the case of the idea of

beforeness the two ideas we would need to consider together are an earlier

idea and a later idea. These are the

only ideas that are appropriate to give us an idea of beforeness. But if one of the two ideas is earlier then

at least it (if not also its later partner) no longer exists. (Alternatively, if it does, its later

partner does not exist, because what is future no more exists than what is

past.) But the whole problem is how we

manage to grab hold of an idea that no longer exists and contemplate it in

memory. Once again, it looks like we

would have to have solved this problem in order to account for the

acquisition of the idea of beforeness.

The idea of beforeness cannot, therefore, be invoked without circularity

in order to explain how we manage to remember. The only way out of the circle would

seem to be to accept that the idea is innate, but that is hardly an option

that Locke would be happy to countenance. Discerning

and Comparing. When we

perceive, it is typically the case that many different simple ideas are

perceived together. Some of these

simple ideas may follow one another in time; others may be disposed alongside

one another in space, and yet others may be bundled together, as figure and

colour are bundled together in a colour patch. Discerning is an operation of the mind that

works like a more acute perception.

When we discern we isolate the individual simple ideas that our perceptions

contain and contemplate them separately from one another. We may also compare various

perceptions, or even various simple ideas with one another. This operation leads us to form ideas of

the respects in which the ideas we are comparing resemble or are different

from one another. Our ideas of

relations arise in this way. These are

highly refined ideas that are not given in sensation, and are not parts or

aggregates of ideas of sensation, but are quite new ideas, though new ideas

that can only arise in us insofar as certain other ideas have first been

given in sensation and reflection and then compared in the right way. It is through discerning and comparing that

we come up with the idea of identity — the relation of being the same as — as

well as the idea of difference — the relation of being different from. The supposedly innate principles of the

identity of indiscernibles (if there is no discernible difference whatsoever

between one thing and another then they are the same), and the law of

non-contradiction (nothing is the same as what is different from it) are read

directly out of these relations. But

since the relations of identity and difference have to be learned by

comparing and contrasting sensations, these principles cannot in fact be

innate. Repeating

and Combining. The mind also has the ability to

imaginatively combine ideas that have originally been given separately from

one another in distinct perceptions.

This is what accounts for all our fantastic ideas as well as for all

our ideas of new inventions. It is

also what accounts for our mathematical and geometrical ideas of magnitudes

in time and space and number, which are generated by taking a unit and adding

it to itself. Locke sometimes

described combinations of multiple replicas of the same idea (like the idea

of a unit repeated twice, three times, etc., to give us our idea of number)

as “repeating.” “Combining,” in

contrast to repeating, involves combinations of different ideas. Naming. Naming is an operation whereby occurrences

of a given idea are associated with a particular word. A word is itself just a special kind of

auditory or visual idea (a spoken word or written symbol). Once we have named our ideas we can use

these names to later call them to mind. Abstracting. Abstracting is the operation whereby

the mind isolates some feature that a number of different ideas have in

common and forms an idea just of that common feature. (It is therefore importantly distinct from

discerning and separating.) Abstraction gives rise to our generic ideas

(i.e., our ideas of kinds of things or groups or classes, as opposed to our

ideas of particular things). All, or

most of our words are in fact names of general ideas. Very few are reserved to name particular

objects. ESSAY QUESTIONS AND RESEARCH PROJECTS

1. Critically

assess Locke’s argument for inferring that our type (i) ideas must be

resemblances of qualities in bodies.

2. Critically

assess Locke’s arguments for inferring that our type (ii) ideas are not

resemblances of any qualities actually inhering in bodies.

3. Locke’s claim

that there is a distinction to be drawn between type (i) and type (ii) ideas

was in part based on an appeal to the claim that type (ii) ideas are relative

(the same water can feel warm to one hand but cold to the other) whereas our

senses never give us conflicting information about the type (i) qualities of

objects (no object ever feels like a globe to one hand but a cube to

another — Essay

II.viii.21). However, this claim seems obviously false in a number of cases

(a pencil in a glass of water looks bent but feels straight, for example). This is a point that was made by Bayle in

note H of his Zeno article (to be read later in this class), by way of

criticism of the Cartesian claim that a “blind impulse” leads us to think

that material things are coloured, but a clear and distinct perception leads

us to think that they must be extended.

However, it works just as well as a criticism of Locke, and both

Berkeley (Principles 14-15) and

Hume (Enquiry XII) used it as

such. Survey Bayle’s,

4. Locke’s claim

that there is a distinction to be drawn between type (i) and type (ii) ideas

was also attacked by Berkeley (Principles

10, drawing on the argument of his Introduction to the Principles) on the grounds that it is impossible to form a type

(i) idea without making use of a type (ii) idea. This is because we cannot think of a figure

without a boundary, and we cannot think of a boundary without employing

contrasting qualities to mark its presence.

5. In his New essays on human understanding, Book II,

Chapter 9, Section 8, Leibniz rejected Locke’s and Molyneux’s answer to the

Molyneux question, writing that “the blind man whose sight is restored could

distinguish [the cube and the sphere] by applying rational principles to the

sensory knowledge he has already obtained by touch” (Remnant and Bennett,

eds. [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981], p.136). Outline the reasons Leibniz gave for his

view and the qualifications he applied to his positive answer. Assess whether Leibniz or Molyneux has the

stronger case.

6. It has

occasionally been charged that Locke’s negative answer to the Molyneux

question is inconsistent with his own position on the distinction between

type (i) and type (ii) ideas.

According to this objection, if type (i) are resemblances of qualities

in bodies, then the newly sighted person ought, on first seeing a globe or a

cube, to be able to suppose that the type (i) ideas they receive from vision

resemble qualities actually existing in bodies, and relate that information

to their tangible experience in order to be able to say which object is the

globe and which the cube. This objection is not supported by the

interpretation of Locke’s reasons for agreeing with Molyneux that was offered

in the reading notes. However, the

issue is not clear-cut. Accounts of

Locke’s position on the Molyneux question can be found both in works on Locke

(e.g., E.J. Lowe, Locke on human

understanding [

7. Locke was not

the only early modern philosopher to have problems accounting for the

phenomenon of memory. Do a comparative

and critical survey of attempts to account for the phenomenon of remembering

by major and minor figures in the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Particularly worthy of study are, in

addition to Locke, Condillac, Hume, Immanuel Kant, and Thomas Reid. |

|

|