Friday, 12 January, 2001, 08:59 GMT

BBC News

URL: http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/sci/tech/newsid_1112000/1112602.stm

Date accessed: 15 January 2001

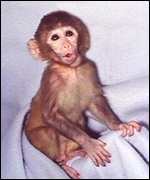

Named Andi, for "inserted DNA" written backwards, the rhesus monkey was born on 2 October at the Oregon Regional Primate Research Center at the Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland, US.

Genetically modified mice have taught us a great deal about human

diseases but there is a huge gap between mice and people

|

|

Prof Gerald Schatten

|

In future, however, the same technique could produce laboratory monkeys carrying genes linked to human diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. Researchers will then be able to use the animals to help develop new therapies.

For many, Andi will represent a step too far

|

"Genetically modified mice have taught us a great deal about human diseases but there is a huge gap between mice and people. GM primates could help fill that gap and translate discoveries from mice to patients."

Exceptional circumstances

The shortcomings of GM mice were underlined by Steve Jones, professor of genetics at University College London, UK. "Often, the disease genes introduced into mice don't cause the same symptoms in the rodents as they do in humans," he said.

UK law and animal ethical codes require researchers to use the least

sentient animal wherever possible

|

|

UK's Medical Research Council

|

But it is not clear that this is an approach that would find much favour - in UK labs, at least. Government regulations demand "exceptional and specific justification" to use primates in experiments. Few licences are sought and fewer still are granted.

The Medical Research Council, which funds most of the animal experimentation in British labs, said: "UK law and animal ethical codes require researchers to use the least sentient animal wherever possible. We expect GM mice will remain the most important species where animals have to be used to help us understand disease and improve health."

GM monkeys would likely make better models of human disease,

especially brain conditions

|

"Most people value large mammals and primates higher than small mammals like mice and rats, because of more human-like characteristics. Primates possess much higher levels of sentience, consciousness and socialisation."

Brain behaviours

But there are circumstances in which some British researchers believe monkey models could be useful. Professor Alistair Compston runs the Brain Repair Centre in Cambridge. He said: "One comes to try to understand the mechanisms of some of the complex diseases of the human brain, especially of the cortex which affect planning, decision-making, changing one's mind, etc.

|

How Andi was made

|

|

Marker DNA carried into 224 monkey eggs by neutralised virus

Eggs fertilised in test tube and implanted in surrogates

Only 40 embryos and five pregnancies resulted

Three monkeys were born alive

Just one, Andi, displayed gene modification

|

Even in Cambridge, though, with its huge concentration of medical research laboratories, there is not going to be a headlong rush into monkey experimentation. Just this week, city planners threw out proposals to expand a local primate research centre. And an unpublished survey for the European Commission suggests that primate researchers themselves are sceptical of the value of GM monkeys.

Professor of physiology at Oxford University, Colin Blakemore, who would countenance the use of modified primates, said there was still much to be gained from working on rodents.

"The use of transgenic mice has been amazingly successful," he said. "As an example, we now have a mouse with a human gene inserted into it which replicates Alzheimer's Disease.

"The mouse develops the pathological changes and some of the behavioural changes. A vaccine has now been developed which can treat this mouse. That vaccine has gone to clinical trials in the US - straight from the mouse to human beings without the necessity for transgenic monkeys."

Categories: 4. Ethical and Social Concerns Arising Out of Biotechnology, 50. Gene Therapy, Genetic Research, and Genetically Modified Species